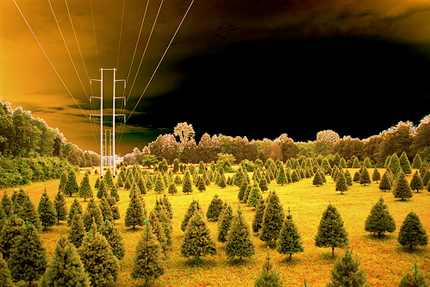

Christmas tree farm, Clinton, TN. Photo by Eric Williams

Those who are needled by the wastefulness of Christmas trees can take comfort: the traditional tree is undergoing a redefinition in terms of its production and marketing but also in the way it’s being bought and used. The shift has gained momentum over the course of a number of years, a convergence of environmental consciousness, economics and emotion, now given an extra boost by a recession-inspired do-it-yourself sensibility.

Not being a horticulturalist or a tree lover or even a long-standing Christmas-tree-buyer, this has been a revelation. People are talking differently about their trees this year — some (but by no means all) are planning on downscaling or simplifying their annual rite or, more striking, they are thinking about ways to make their purchase more environmentally responsible.

Just as with the recent resurgence of knitting, quilting and food canning, a yearning underlies this conversation, a desire to turn back the clock, at least symbolically, on our consumer excesses, a recoil from the anonymous and disconnected life represented by the mall, the supermarket and the big-box store toward something more local and home-grown.

The idea of cutting down a living tree, shipping it hundreds of miles, using it for a few weeks and then disposing of it along with the trash rankles a growing number of consumers. Artificial trees present different concerns, primarily about health risks and the ethics of overseas manufacturing. And now there’s a growing list of alternatives — novelty trees, rental trees and sustainably grown trees, as well.

Christmas trees and wreaths in store window display, Library of Congress, 1941-1942

“Fifteen years ago, you wouldn’t give a second thought to buying a Christmas tree,” said Penne Restad, a senior lecturer in American history at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of Christmas in America. “Now there is a heightened consciousness surrounding the whole thing.” She sighed and added, “The tree becomes just one more thing to get right.”

That the Christmas tree has become a symbol of our contradictory feelings about consumerism isn’t all that surprising. On the one hand it represents the pleasure of giving and receiving gifts, a provider of abundance in the gloomy depths of winter and a twinkly sense of family memory. But on the other, it’s a source of anxiety about excess and over-commercialization. To some, the Christmas tree represents gaudy materialism.

The tension has been there right from the start. It’s generally agreed that the Christian practice of bringing an evergreen tree into the home, which arose after the Reformation in the German region of Alsace-Lorraine, co-opted the pagan Roman ritual use of the evergreen as a symbol for regeneration and fertility. A 1605 diary entry from Strasbourg describes an indoor fir tree decorated with “roses cut out of many-colored paper, apples, wafers, gold foil, sweets.” The practice gained particular ground with German Protestants, as the tree became an emblem of their faith. German Catholics, on the other hand, favored the Krippe, or holy manger, an import from the more representational tradition of Italian Catholics.

Germans took the Christmas tree tradition to the New World. In the 1830s, the practice was still so odd that a Manhattan writer named Charles Haswell braved “a very stormy and wet night” to travel all the way to Brooklyn for the novelty of watching German immigrants trim a tree. By 1843, however, New York newspapers were advertising Christmas tree decorations. And by 1851, vendors could rent Manhattan sidewalk space for a dollar and sell evergreens to city slickers, just as they do today.

Some Victorians resisted the custom. In 1845, the novelist and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child wrote to a friend, “The Puritan blood still flows too briskly in my veins to allow me to relish over much the Christmas tree.”

A hint of this Puritan resistance can be picked up in the debate today. On the one hand, there is the cut tree, fragrant and real, grown on a farm hundreds of miles away (especially if you live in the southwest) and shipped to you by truck. This type of Christmas tree, according to Robert Cox, a horticulturalist at Colorado State University, is “a crop just like corn.” It’s planted efficiently, treated with herbicides and pesticides, harvested mechanically — an agricultural product, like any other. We buy it, decorate it, use it and then throw it out with the trash, to be hauled away by our local municipality.

In most cases, this tree will either be turned into mulch (a process that entails the use of more fuel) or buried in a landfill. But according to John Mexal, who teaches in the department of agronomy and horticulture at New Mexico State University, environmentalists in Alabama and other states are using discarded cut trees to help build fish habitats in lakes and ponds.

Even with such innovative recycling programs, the living tree has been battling competition from the artificial-tree sector. In 2002, according to the National Christmas Tree Association, Americans bought 7.4 million artificial trees. In 2008 they bought 11.7 million (the number of live trees purchased increased as well, from 22.2 million to 28.2 million). The association represents approximately 1,100 Christmas tree farmers and retailers across the nation and it sponsors the celebrated annual ritual of choosing the White House tree. But its primary goal seems to be to counter the growth of artificial-tree sales.

Along with issuing sobering warnings about the lead threats of PVC — the material of most artificial Christmas trees — the association’s website describes how the first fake trees were made by the Addis Brush company, which also manufactured bathroom cleaning tools. “Regardless of how far the technology has come, it’s still interesting to know that the first fake Christmas trees were really big green toilet bowl brushes,” the website sniffs.

Rick Dungey, the association’s media representative, makes a more persuasive argument against these products. While acknowledging the convenience of artificial trees, he noted that 80 percent of them are manufactured in China, often under working conditions that are difficult to document. “Young people are much more environmentally aware,” he added. “They aren’t taken in by the artificial-tree argument. They know it’s just a hunk of metal and plastic made in a factory somewhere.”

Bill Quinn, who runs Christmastreeforme.com, a retailer of artificial trees, subtly evades the PVC question. He points to the lead in stabilizers used in the wires for Christmas tree lighting as a more pronounced health risk. He also cites design innovations that have reduced the quantity of PVC in newly produced artificial trees. The outer branches are now made with polyethylene, while PVC is reserved for the inner branches, which need to be denser for a full, lush look.

When it comes to convenience and cost over time, Quinn is quietly bullish. You can unzip one of his trees from their specially designed bags and assemble it in 30 minutes. He started selling artificial Christmas trees in 2004 and has watched his sales steadily climb. Much of this was due, he admits, to the boom in new home purchases. But although that market has dried up recently, he’s found profit in his line of novelty trees. He had a hit a few years ago with an upside down Christmas tree, and his all-black trees sell well to customers who want to shake up convention with a punk aesthetic.

But neither traditional farmed and cut trees nor artificial trees appeal to an increasing number of consumers for whom a Christmas tree signifies ethical, even spiritual, values. According to Restad, a tree is “almost a cosmic statement, analogous to someone declaring that they are a vegan or carrying around their yoga mat.”

If they happen to live in the right climate, consumers can even rent trees. “This is a way for my customers not to feel guilty. They’re not responsible for cutting down a tree and they’re not buying an artificial one, either” said Christine McDannell, who runs Adopt-A-Christmas Tree in San Diego.

McDannell was introduced to the idea several years ago when she rented an evergreen from a local activist-entrepreneur. The tree arrived a few days before Christmas, delivered by singing elves (otherwise known as out-of-work actors) and with a certificate of authentication. McDannell was advised to leave the tree outside for a few days, to help it acclimatize, and then bring it indoors for no more than a week and a half. Afterwards, the elves returned in civilian clothes to remove the tree and re-plant it in her choice of a park, private property or local fire-damaged land.

Four years ago, Adopt-A-Christmas Tree rented out 80 trees. McDannell bought the business in September 2007, and this year, she’s planning on renting out 500.

A further refinement on the concept has taken place in Dorset, England. At Treesforrent.com, customers not only rent Christmas trees but are offered the chance to have the same tree delivered to them yearly, like a beloved relative returning for a holiday visit.

Those who continue to purchase live trees annually may take comfort in the sustainable farming making inroads in the Christmas tree market. John Harrington, a professor in the College of Agriculture, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at New Mexico State University, works with local farmers to harvest indigenous Christmas trees, mainly Douglas and white fir, from natural forest stands without the application of pesticides or herbicides.

As opposed to conventional Christmas tree farming, where trees are planted like crops in rows to maximize production, this technique trades short-term expectations of high yields and large profits for lower but more consistent yields over time — say 80 to 100 years – with greater long-term profit per acre.

Growing trees this way has related advantages, not all of them quantifiable — it encourages the growth of other timber crops from the same land, it’s a boon to local wildlife, it helps encourage the health of the local watershed and it reduces the potential for wildfires. Natural stands of trees add aesthetic value. The method also involves fewer startup costs (no seedlings, irrigation investments or planting costs) and lower maintenance (less weed control, shearing and shaping costs).

Harrington quotes the Society of American Foresters when defining his goal of sustainable practice — an attempt to “maintain the health, productivity, diversity and overall integrity of the forest” in the context of human activity and use. The resulting trees are spaced farther apart under the forest canopy and therefore take longer to harvest, increasing their price. And their shapes are less uniform than conventionally farmed trees. New Mexicans have to balance those tradeoffs against the cookie-cutter-farmed tree trucked in from half a continent away, like any other domestic consumer product, and sold at a big-box store for less. But if they choose one of these indigenous, sustainably grown trees, they can take comfort in knowing that they have left the lightest possible footprint on the land.

This array of possibilities in the world of Christmas trees, part of the plethora of choices that make design and consumption such ethical battlefields these days, “reflects the entrepreneurial culture we live in,” said Restad. “The product becomes just another sign of your state of goodness.” Although she regrets that the anxiety of choosing a tree has replaced the unthinking pleasure of ritual, she notes, “It really has become a metaphor for postmodern American life.”

And just in case you’re wondering, there is a Christmas-tree app for your iPhone.

Additional research by John Duvall