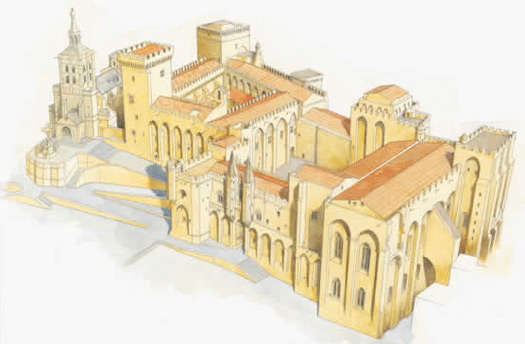

Palace of Popes, Avignon France

Before Twittter, a serious connoisseur might study the Mona Lisa for 20 years before reaching a conclusion. Today, the average museum visitor looks at a work of art for 42 seconds.

Now 42 seconds is a long time compared to the 11 seconds that most shares are owned by high frequency trading machines. But for the Popes of culture and media, who met last week for the third Avignon Forum, this shallow cultural scanning is a reprehensible downside of “culture for everyone” — theme of this year's gathering. (My report from last year's Forum is here).

The popes perked up when anthropologist Arjun Appadurai told them to think of culture as a “tool for managing uncertainty” and when Frederic Mitterand, the French minister of culture, described the digital age as a “cognitive revolution…a new ecology of mind.”

French elites have good historical reasons to be nervous about revolting masses. As today's masses reflect on the heavy price they must now pay for their masters' gambling habit, culture as “a way of organizing people's understanding” has obvious attractions.

“What are the new channels for transmission?” a policy panjandrum asked — entranced, or so it sounded, by the prospect of hooking up citizens to Seresta-dispensing cultural drips.

As if on cue, a band called Playing For Change invited us to sing along sweetly to the words of Bob Marley: “Let's Get Together and Feel Alright.”

Follow the Money

A desire to use culture for social control is not unique to the digital age. The connection between culture and money goes back even further.

I was impressed at this point by the candor of the man from Ernst&Young. His slides featured the “ME Industries” — and I had thought it was just me who believed that modern media fosters mass narcissism. Then I realized that ME was shorthand for Media and Entertainment industries and that no disrespect was intended. On the contrary, the man from E&Y was on a serious quest: “Monetizing digital media and culture: creating value that consumers will buy.”

Monetization, or its lack, was a sensitive issue for this gathering. Digital is proving a mixed blessing. It was not a surprise that the issue of piracy soon took central stage. From the European Commisisoner down, a panoply of popes waxed righteous about the necessity for artists to be paid fairly for their creativity. Any crumbs left over from the cultural cake could be divided among the publishers, they added humbly — but the Rights of the Artist were paramount.

Mind you, those crumbs soon add up. Pope Philippe Dauman of Viacom, for example, was paid about $34 million in 2009. Mr Dauman's “compensation” is roughly 3,000 times more than what most of my artist friends are paid. It's fully 48,000 times more than is available to "Bottom of the Pyramid" types — among whose number, in my experience, the most vibrant culture and creativity is often to be found.

But pah! to the politics of envy. These vulgar details commanded little attention in Avignon. The popes and their cardinals spoke as one: copyright protection is a matter of principle, not profit.

Innovation

There was much talk of micropayments in Avignon, but not much about content innovation, until Joichi Ito took the stage. Ito, a venture capitalist who is also chair of Creative Commons, observed that their huge size made it hard-to-impossible for media giants to be innovative. Change comes from the edge and with the best will in the world, the “E-Suite” of a media giant is a long way from most edges.

Being “an internet company,” Ito told us, is not about a choice of technology platforms. It's a philosophy. It's an attribute of companies that are collaborative, and that don't expect media products to emerge shiny and perfect from centralised (and very expensive) planning and marketing systems.

True internet companies innovate cheaply, Ito continued. In his experience as an investor, a talented team could often create a “minimum viable product,” as the basis of a start-up, for $30,000. This amount, he jested, would barely buy a decent lunch for the Viacom Board.

Into the Non-Linear Social Space

A man from Bain&Co predicted that more than 20 percent of book sales could be digital by 2015, and that these would capture up to 25 percent of the “overall value pool.” So everyone would be swimming in money? Not necessarily. Digital platforms change important relationships between retailers, publishers and authors — such as who gets how much. A publisher who “merely transitions words from page to screen” is likely to be a loser, we were told. According to Bain&Co, new formats such as ‘non-linear social’ are where the opportunity lies.

I paid attention. “Non-linear social?” How do you do that?

One of the other consultants in Avignon tried to explain: “Media content bundles will not be products, but services.” To be sellable, these services need to offer something that stand-alone, read-only digital products cannot: customized contextual links, live encounters with the author, extra video-bits; things like that.

One hopes the media giants are not pinning their hopes on interactive books. Fifteen years ago we were told TV would become interactive and that never happened. At this point we could have done with a reality-check from a working non-linear-social writer — such as Seth Godin or Cory Doctorow or Doug Rushkoff.

Another question raised, but not really answered, concerned mobility. Many of the promised new content services will be accessed via mobile devices. What will be the interesting ways for a writer to exploit that opportunity? (Hint: don't tell me it's to find a pizza within ten yards.)

Micropayments offer a more tangible opportunity. They should make it easier for writers to sell content in chunks — much as Dickens and Balzac published their work. All you need to succeed is to be as talented as Dickens or Balzac.

Unbundled

But suppose one does not want to be "bundled." Is there an alternative?

As I suggested to a group of young design critics recently, perhaps the function of a writer's output is to start conversations and that the writer should consider speaking her words in a place rather than pressing ‘send.’ In Avignon-speak, this kind of service would be “non-delocatable.”

Sitting in the Palace of the Popes, my thoughts wandered to the form and content of the confessional. This tried-and-tested off-grid format uses inexpensive equipment. The confessional box and the rosary are often beautifully designed in natural materials. Its users are embodied. Its mode of operation and instructions are easy to follow.

Above all, the confession's value proposition is impossible to beat. The ME industries offer endless distraction — but little satisfaction. A low-tech, low-cost, person-to-person confession, in contrast, offers the client…. Absolution.

Could that be the lesson, for the writers of Avignon?

Comments [1]

12.02.10

04:44