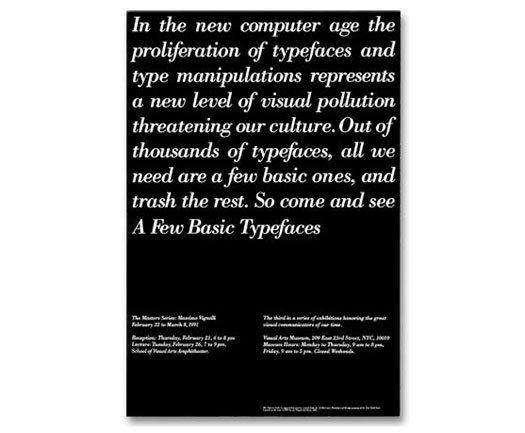

Massimo Vignelli, Exhibition Opening Invitation, School of Visual Arts, New York, 1991

Here are some things I was not allowed to do as I began my first job:

Use any typeface other than Helvetica, Century, Times, Futura, Garamond No. 3, or Bodoni.

Use more than two typefaces on any project.

Use more than three sizes of typefaces on any project.

Begin any layout without a modular grid in place, including a letterhead or a business card.

Make visual references to any examples of historic graphic design predating Josef Muller-Brockmann or Armin Hoffman.

Incorporate any graphic devices that could not be defended on the basis of pure function.

When I arrived as the most junior of junior designers at Vignelli Associates in 1980, my portfolio couldn't have been more eclectic. Filled with excitable homages to everyone from Wolfgang Weingart to Pushpin Studios, my design school work begged for a diagnosis of Multiple Designer Personality Disorder. You might have expected me to rebel against the strictures to which I was subjected by my first employer. Instead, I willingly submitted to them. For ten years. And, as a result, I am a better designer today.

You may react to this with horror. That was certainly the reaction when the now-ubiquitous Amy Chua burst on the world several weeks ago with her Wall Street Journal essay "Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior," an excerpt from her memoir Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. The essay, which has been called the "Andromeda Strain of viral memes," made a no-holds-barred case for subjecting the young to draconian rules. No TV, no sleepovers, no video games. Instead, 10-hour violin lessons. Chua also advocates zero tolerance for A-minuses on tests and even (heads up, graphic designers!) the rejection of less-than-adequate handmade birthday cards. In an age of permissive parenting, the Tiger Mother struck a nerve: as of this writing, the original essay has received 7,600 comments and counting.

All of this got me thinking about my own strict upbringing as a designer. I was completely non-ideological when I graduated from college. I didn't regard Helvetica-on-a-grid as the apotheosis of refined reductivism as did the Swiss modernists or the founders of Unimark. But nor did I see it as the embodiment of Nixon-era corporate oppression as did designers like Paula Scher. To me, it was just another style.

But it was a style I liked, and I submerged myself happily in its rigors when I took my seat at my first job. The rules weren't written down anywhere or even explicitly communicated. They were more like unspoken taboos. Using Cooper Black, like human cannibalism or having sex with your sister, simply wasn't done. For many young designers in the studio, the rules were too much. They resisted (futilely), grew restless (eventually), and left. By staying, I learned to go beyond the easy-to-imitate style of Helvetica-on-a-grid. I learned the virtues of modernism.

I learned attention to detail. Working with a limited palette of elements leaves a designer nowhere to hide. With so little on the page, what was there had to be perfect. I learned the importance of content. Seeing Massimo design a picture book was a revelation. No tricky layouts, no extraneous elements. Instead, a crisply edited collection of images, perfectly sized, carefully sequenced, and dramatically paced. Nothing there in the final product but the pictures and the story they told.

I learned humility. I was a clever designer who loved to call attention to himself. The monastic life to which I had committed left no room for this. It became my goal, instead, to get out of the way and let the words on the page do the work. Ultimately, I learned about what endures in design. Not impulsiveness and self-indulgence, but clarity and simplicity.

There was another side to modernism, though: its legacy as the great leveler. Massimo once told me that one of the great aspects of modernist graphic design was that it was replicable. You could teach its principles to anyone, even a non-designer, and if they followed the rules they'd be able to come up with a solid, if not brilliant, solution. To me, this was both idealistic — design for all — and vaguely depressing, a prescription for a visual world without valleys but without peaks as well. Sometimes impulsiveness and self-indulgence were no more than that, but every once in a while they were something you might call genius. I worried about genius.

So I permitted myself the occasional indulgence after I had been at Vignelli for a while. Once I did a freebie poster using Franklin Gothic for the AIGA. "Why did you use that typeface?" asked Massimo, sincerely baffled. I think he would have been satisfied if I said that I had lost a bet, or that I was drunk. Instead, I just, um, felt like it. I mean, Ivan Chermayeff used Franklin Gothic all the time! Was it really that bad? Another time, designing a catalog for an exhibition of vintage photographs of the American west, I created a cover that imitated a 19th-century playbill. What pleasure it was to work with a half-dozen typefaces out of Rob Roy Kelly's fantastic book, American Wood Type. In so doing, I managed to actually break at least three rules at once (unauthorized typefaces; too many typefaces at once; and, perhaps worst of all, historical imitiation). Massimo pronounced the result "awful," a word he could (and still can) provide with a memorable inflection while seeming to gag. I still like that cover.

By the time I left Vignelli Associates in 1990, I felt I was ready to move far beyond the limiting strictures of modernism. The period of graphic self-indulgence that followed is now a bit painful for me to contemplate. After a time I came to appreciate the tough love that my favorite mentor had so painstakingly administered for a full decade. The turning point came in about 1996, when I received a call to design a book for Tibor Kalman. This was the monograph that would become Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist. I was surprised and pleased. As a designer at Vignelli Associates, I had followed the work of M&Co. with interest and admiration, noting how often they broke every design rule in the world with cheekiness and impunity. I arrived at my meeting with Tibor, brimming with notions about how my book design would embody the irreverence of the M&Co. worldview.

Tibor listened patiently to my ideas — there were lots of them — and then paused for a long time. "Well, yes, you could do some stuff like that," he responded carefullly. "Or, we could do something like this. You could work out a good clear grid. We could edit all the images really carefully. Then you could do a really nice clean layout, perfect pace, perfect sequence. You know," he added with a smile, "sort of like a Vignelli book. And then we could fuck it up a little."

I then realized that, whether you credit (or blame) your mother or your mentor, you can never fully escape your influences. The rules you grow up with are what make you, as a person and as a designer. The trick is to remember, every once in a while, to fuck them up a little.

This essay was originally published in January, 2011.