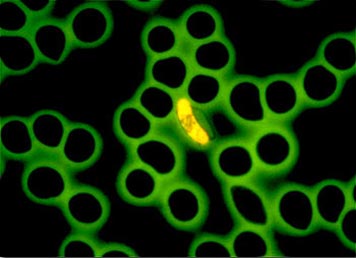

Malarial parasite revealed through the use of fluorescence microscopy.

During Design Observer's hiatus last week, I had the opportunity to visit a research lab at National Jewish Hospital in Denver, Colorado where, among other things, I inquired about the state of modern microscopy. To be honest, the term "microscopy" was not even remotely familiar to me: what I asked for was a glimpse through a microscope, a chance to peer into a petrie dish — some evidence that what happens in the lab environment has a visual component to which I could relate.

It turns out that microscopy, like most things, has basically gone digital: no surprise there. But what did surprise me was the realization that scientific observation obliges its participants to engage in a kind of resistance to imagination. To simply gaze at a specimen is not enough: such viewing lends itself to speculative assessments that are not necessarily productive with regard to tangible results. If it is the scientist's role to quantify data, then to simply observe the evocative beauty of what the "scope" reveals is essentially a meaningless — if not an altogether irresponsible — act.

I found this discrepancy (between observation as an art and as a science) at once fascinating and revealing: fascinating to consider the act of observation as a test of wills, and revealing insofar as design is, quite simply, anything but a science. And yet, does not the very act of observation require, for the designer, a certain amount of scrutiny and analysis? After all, we routinely engage in a set of actions that might be said to rely specifically upon keen observation: oversimplified as this seems, we examine, we think, we edit and we resolve. Fold in the complex incentives of identity and stragegy and audience, add the formal imperatives that define the visual artefact in question and the designer's role may begin to seem like that of a scientist. But nothing could be further from the truth, for as scientific as we would like to imagine ourselves to be, the act of making design depends upon an element of mystery that is, quite frankly, anathema to science.

And therein lies the real difference.

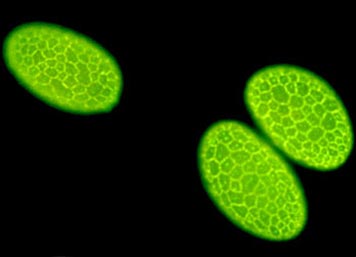

Green autofluorescence of pollen grains visualized using widefield fluorescence microscopy.

In Denver, I witnessed a fascinating demonstration of something called fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence is the property of some atoms and molecules to absorb light at a particular wavelength and to subsequently emit light of a longer wavelength after a brief interval, which is known as its "fluorescence lifetime. " (A more complete explanation can be found here. ) In the lab, I saw a quicktime movie generated from multiple still photographs: at 15 seconds and more than 55 megs it was a tour-de-force of light and technology — like a James Turrell light sculpture dancing a deft pas de deux. But it didn't merely perform magnificently (although it did that too) it actually meant something, something specific and real and deeply consequential. Art in the service of science — but art nontheless.

Of course, the use of electrons, photons, phosphorescent light and fluorescence microscopy largely remain a mystery to me, but not because their capacity for imaging is itself mysterious. Rather, as a visual maker I am used to filling in the blanks with invention, or inflection, or even interpolation, all of these born of the creative license that comes with being a designer. Not so with scientists: imagine the consequences if researchers invented their results.

Nevertheless, we have something important to learn from scientists and their tools of observation — which brings us back to microscopy. I am not trying to minimize the importance of design any more than I am attempting to demystify the nature of scientific observation. But there is something about the harnessing of light and technology in search of a kind of concrete, factual truth that is, to me at least, nothing short of mesmerizing. As imperiled a commodity as it is, truth remains the nucleus in so much of what any of us ultimately seek, not only as designers but as active participants in a cultivated world. (And to think that it took the cultivation of a single cell to make this clear to me.)

I returned home to the evangelist scare tactics framing the National Republican Convention here in the US, followed by reports of extremist scare tactics fueling upheaval in Russia. Writing paralysis held me in a kind of suspended animation for several days as I wondered: how could I write something for Design Observer that wouldn't trivialize world events of such magnitude? As my thoughts drifted to what I witnessed in Denver, I thought back to the notion of the fluorescent lifetime: brief, but tangible; illuminating truth and demystifying the unknown; advancing our capacity to see what's in front of us, or inside us, or ahead of us — and to comprehend what's real. At the end of the day, this strikes me as a worthy goal for any of us.