Bilbao's Abandoibarra area, 1992, before modernization. Via Skyscraper City.

The Basque city of Bilbao was a pioneer in Europe in the use of showcase cultural buildings as a trigger for urban regeneration. Just a generation ago the city's waterfront was an industrial port. Today, in addition to the Guggenheim itself, its architectural landmarks include bridges by Santiago Calatrava and Daniel Buren, and an apartment block by Arata Isozaki.

...And after modernization, in 2005, with Guggenheim Museum in place. Via Skyscraper City.

But as with Japan, where the technique was invented (landmark structures were called “antenna buildings” during their bubble economy of the 1980s), the global crisis finds Bilbao asking: now what do we do?

As things stand, the region is still committed to a new “thrust for modernization." Bilbao's strategy, shaped with input from Global Business Network, is to become a "city for innovation and knowledge." There is talk of re-branding Bilbao as Euskal Hiria (Basque City), a “poly-centered global city” that would encompass the Donostia–San Sebastian, Bilbao, Vitoria–Gasteiz region as single geographical-economic entity.

Positioned as a hub linking the north of Europe to the South, the idea is that Euskal Hiria would attract an army of highly paid lawyers, financial and marketing consultants, and iPad-toting creative professionals of all kinds. These knowledge workers, the strategy implies, would snap up the expensive apartments that now lie empty along Bilbao's waterfront.

For all this to happen, Euskal Hiria would need a symbolic edifice to represent this Basque Global City to the world in the way that the Guggenheim does for Bilbao.

The scenario confronts two obstacles.

The first is that buildings conceived as icons, spectacles or tourism destinations have fallen victim to the law of diminishing returns. Bilbao's Guggenheim is now one among hundreds of me-too cultural buildings around the world. As their number has grown, their capacity to attract attention, or differentiate their host city, has declined. Spoiled consumer-travelers are liable to lunch in the café, buy the t-shirt, and move on. That's not a great return on all the time, work and money needed to bring these totemic edifices about.

The second objection to the Euskal Hiria strategy, and Guggenheim 2 as its emblem, is that they would stand for the high entropy economic model that caused the global crisis in the first place — and that is now dying.

If the iconic cultural building as a catalyst of development has run its course, and the Real Estate Industrial Complex is gone forever, is there an alternative?

A conference in Bilbao last week, organized by Fernando Golvano and Xabier Laka, challenged speakers to propose new models of development based on more artful and sustainable uses of the region's social, landscape and natural assets.

My contribution was to say that a bioregion — more than a high-entropy “knowledge hub” preoccupied with abstraction — could be the ideal basis on which to re-imagine the future development of the Basque Country. At the scale of the city-region, a bioregional approach re-imagines the man-made world as being one element among a complex of interacting, co-dependent ecologies: energy, water, food, production and information.

The beauty of this approach is that it engages with the next economy, not the dying one we have now. Its core value is stewardship, not perpetual growth. It focuses on service and social innovation, not on the outputs of extractive industries. Being unique to its place, it fosters infinite diversity.

The idea of a bioregion also changes the ways we think about the cities we have now. It triggers people to seek practical ways to re-connect with the soils, trees, animals, landscapes, energy systems, water and energy sources on which all life depends. It re-imagines the urban landscape itself as an ecology with the potential to support us.

A bioregion is literally and etymologically a "life-place" — a unique area, in the words of American writer Robert Thayer, that is "definable by natural (rather than political) boundaries with a geographic, climatic, hydrological, and ecological character capable of supporting unique human and nonhuman living communities."

A growing worldwide movement is looking at the idea of development through this fresh lens. Sensible to the value of natural and social ecologies, groups and communities are searching for ways to preserve, steward and restore assets that already exist — so-called net present assets — rather than thinking first about extracting raw materials to make new iconic buildings from scratch.

One idea already floated in the Basque region is to locate a Guggenheim-type facility in the Biosphere Reserve of Urdaibai.

Urdaibai

This spectacular salt marsh and coastal landscape on the Bay of Biscay coast covers an area of 220 km2 (137 sq miles) and contains only 45.000 inhabitants.

My response, at the conference, was that a “pure” piece of nature, such as Urdaibai, is not the ideal starting point for a new regional narrative. It would reinforce a myth that sustainable development involves returning to pure and unsullied nature. A better priority, I proposed, is to focus on ways to restore and enhance the flows and ecologies of city and countryside.

A number of artists in the Basque region, it turns out, are already exploring this approach. In a variety of ways, they are engaging citizens in new kinds of conversations and encounters whose outcome is transform the territory — but indirectly.

Maider López for example, invited citizens to create a traffic jam on the sides of Mount Aralar, where normally traffic is light. More than 400 people in 160 cars responded to the invitation. For five hours of a mid-September day participants clogged up the winding roads in a variety of artful ways.

Maider López's orchestrated traffic jam on Mount Aralar.

López, who describes her work as “a poetic approach to community engagement in daily life,” told us her traffic jam was to get people thinking about the automobile’s impact on the landscape — only to do so without saying what to think or do about it.

Another artist, Ricardo Anton, presented a project about trash. His approach was to use subtle signs and signals — such as framing dumping site blackspots with CSI-like striped tape.

Anton explained that these kinds of projects “create new spaces for encounters in an ever changing territory of relationships.” They are a variety of what he called “micro-politics” that in his experience are more effective than telling citizens what to do, or how to behave.

Saioa Olmo Alonso described an enchanting project in the abandoned Bizkaia Theme Park that closed in 1990.

Seventeen years after shutting its doors, the original Ghost Train, Octopus and Crazy Worm were gradually being overgrown. Alonso invited groups of citizens to imagine new possibilities for an area once dedicated to fun and entertainment. These light-touch encounters create what Alonso calls “micro-utopias”...whose positive energy complements the formal planned features of a town's development.

In Bilbao I also caught up with Asier Perez, from Funky Projects. Asier had wowed a Doors of Perception event in 2004 with his presentation about cactus ice cream as a communication tool — so I was keen to get an update.

Combining artful interventions and service innovation, Funky Projects' portfolio now includes service design for Telefonica and Pepsico, as well as many projects for the government and third sector on social innovation and the development of new kinds of tourism services. Funky Projects is developing strategies for the Gorbeialdea region — Euskadi's “green heart” — where local authorities developed the idea of being a shepherd for a day or listening to animal sounds by night.

The work of these artists and designers anticipates a new approach to regional development. With the bioregion as their canvas, they are helping different kinds of groups and communities imagine new uses for the places and contexts that surround them.

They are not alone. A new kind of economy — a restorative economy — is emerging in a million grassroots projects and experiments all over the world. The better-known examples have names like Post-Carbon Cities, or Transition Towns. The movement includes people who are restoring ecosystems and watersheds. Their number includes dam removers, wetland restorers and rainwater rescuers. The movement is visible wherever people are growing food in cities, or turning school backyards into edible gardens. Many people in this movement are recycling buildings in downtowns and suburbs, favelas and slums.

Thousands of groups, tens of thousands of experiments. For every daily life-support system that is unsustainable now — food, health, shelter and clothing — alternatives are being innovated. What they have in common is that they are creating value without destroying natural and human assets. The keyword here is social innovation — and the creation of social goods — because this movement is about groups of people innovating together, not lone inventors.

Listening to the artists' stories in Bilbao, however, I reflected that it would be hard work to sell these kinds of project to policymakers and development professionals. In their world, ideas are the easy part. What's hard is getting disparate actors to collaborate.

In that respect, iconic building projects can be an effective way to focus and galvanise the energies of disparate stakeholders.

But if shiny new cultural buildings are a thing of the past, could a new kind of icon take their place?

Someone suggested that perhaps Urdaibai should be host to something like the Eden Project:

The drawback with this idea is that Cornwall already has the original Eden Project — so why copy the same, only 10 years later?

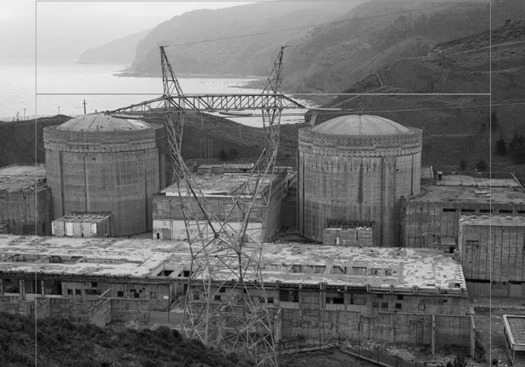

At this point, as if by fate, Xabier Laka, one of the organizers, mentioned the Lemoniz Nuclear Power Plant.

Construction of this huge facility was nearly complete when, 28 years ago, Spain's nuclear power expansion program was abruptly canceled following a change of government. The Lemoniz plant was never commissioned. Since then, several propositions have been made to reconvert the place for other uses — but none has taken off.

Bingo! I thought. This could be the perfect next icon for the Basque Country. I could see the headline: "Lemoniz: from Nuclear Energy to Social Energy."

It could become a year-round showcase and hub for the multitude of projects that are out there in the territory, only invisibly so: productive urban gardens; low energy food storage; communal composting solutions; re-discovery of hidden rivers; neighborhood energy dashboards; de-motorized courier services; software tools to help people share resources.

Now all I need is to persuade the nice Mr. Galán, who owns the Lemoniz site, that now his Iberdrola Tower is more or less complete; this should be his next sustainable innovation project.

Comments [10]

Lemoniz is a privileged place in the Biscay coast right next to Urdaibai, 45 minutes away from Bilbao and enclosed by dense vegetation and rock.

http://www.google.es/images?q=lemoniz&um=1&ie=UTF-8&source=og&sa=N&hl=es&tab=wi&biw=981&bih=576

Lemoniz story is pretty unique and , could well illustrate the debate on the use of nuclear energy.

30 years ago some 180 hectares of land were devoted to the construction of a nuclear facility. Shortly before the end of the process, popular pressure and coercion of ETA stopped construction and so began the moratorium. This moratorium encloses a latent story in the Basque collective consciousness, a hard to tell story that should be ended collectively..

That aim is the germ of several proposals, one of them being Esnatu lemoiz! (Wake Up Lemoniz!)

Esnatu Lemoiz! proposes a non-aggressive procedure, a theoretical framework for an open and comprehensive debate to define hypothecical futures for the facilities

And so the Initiative includes 3 proposals.

1. The Nuclear Debate.

An international and social forum including a series of lectures on the energetic model, The nuclear power, Sustainability and Post-Industrial Regeneration, paritipatory urbanism...

Professional, social, academic, artistic discussions on some of the most important contemporary issues ( nuclear power, industrial regeneration , participatory urbanism ...) An inclusive social forum on the future of the ruined facilities.

2. Architectural Competition.

Young architects and architecture students rethink Lemoiz and send their theoretical proposals. The competition alone could project the image of Biscay in relationship with architecture.

3. Nucleart

Pursuing a broad social participation raises the confluence of cultural and artistic events of all kinds around the same idea, with an exceptionally fertile conceptual support.

This initiative does not transcend the theoretical but aims to build consensus on future prospects and become a new standard of performance. Plus given the enormous social burden around Lemóniz history, only a public debate could legitimize a possible outcome. Moreover, the initiative could project the image of Biscay internationally and meet the needs of our polititians. In addition Iberdrola, the initiative could be a convincing demonstration of social responsibility.

If you have further interest on the proposal I´ll be glad to share it with you.

Good luck with Iberdrola.

03.30.11

07:07

Key regeneration themes are: university graduates, technology cluster of firms, local government support and the innovative business incubator run by Norman Evans. Encouraging former students to return here to live / educate their children at mid-life stage is working well for middle class professionals.

03.31.11

02:07

We can have both of them ;-)

...and that for sure would be a distinctive hallmark for us.

Nice point by the way.

04.01.11

03:33

Rebecca, my concern about knowledge clusters as an engine of development is a too-narrow definition of the word on technology and abstraction. I'd like to see knowledge clusters for which their bioregion, and constituent social and natural ecosystems, were the main focus.

Anibal, yes you could have both - but my preference would be a focus on contextual information and research - and, please, no shiny buildings with mirror glass windows and guards. That would really set your region apart

04.01.11

04:35

They are actually many initiatives related to the site. As you suggested we are gathering and frame them to get some institutional support.

Here is a briefing of the presentation in case any of you want to take a look.

http://issuu.com/diego_soroa/docs/wake_up_lemoniz_?viewMode=presentation

04.01.11

12:04

04.01.11

12:29

04.08.11

03:35

http://www.de-architectura.com/2011/01/leffetto-bilbao-e-finitosi-sono.html

http://blog.aboutbc.info/2011/01/26/nuestro-comentario-sobre-el-efecto-bilbao-en-una-web-italiana/

http://blog.aboutbc.info/2011/01/25/%C2%BFesta-acabado-el-efecto-bilbao-o-es-que-algunos-no-entienden-lo-que-es-de-verdad/

04.08.11

03:43

How is bilboa in any way diofferent, One might as well argue about the rebuilds of Vienna, or Paris or georgian Edinburgh. each invokes a mood of courage & reflection and forward looking at a time when uncertainty & fear prevailed.

These remarks are in no way to diminish the fine work being done in present day Spain and Portugal : perhaps relative economic recessions are a necessary pre-condition to liberating creativity: Bauhaus was borne of a severe post war depression; however counter-intuitive that may be. Re-use and urbane sensibilities deepen :"cultural awareness"> I did not single out the colisseum because it really reflects the beginnings of "developer" mentality and a forced "historicism" in appealling to "en masse".

04.14.11

01:36

07.12.15

06:50