If architectural bravura was an indicator, the answer would be yes. The older tower (above) which looks like something out of Batman, is the University of Pittsburgh's Cathedral of Learning. The brutal black one (below) is the HQ of UPMC, an $8 billion healthcare colossus. The black tower, says its main tenant, is “tangible evidence of Pittsburgh's transformation into an international center of medicine, technology and education.”

UPMC, which runs 20 hospitals in the Pittsburgh area, and has 48,000 workers, is by far the city's largest employer. Across the US, only Boston has a higher proportion of health workers.

Their sheer size makes some people in the city nervous that Eds & Meds might be economic bubbles, and that their dizzy rates of growth — in prices, as much as in jobs — might be unsustainable.

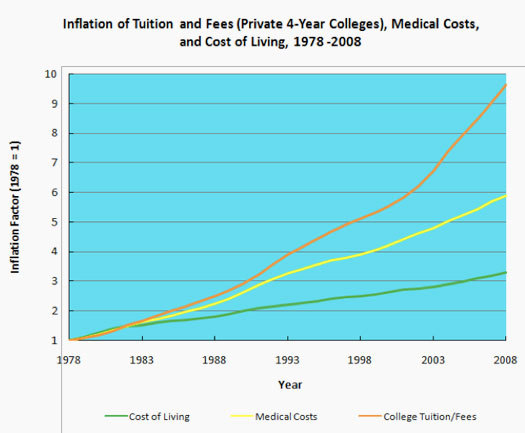

The escalating costs of US healthcare are well-enough known. At 16 per cent of GDP, it is now the largest sector of the US economy — almost double the average for developed nations.

One reason US healthcare is so expensive, as Aldous Huxley wrote in 1946 in The Doors of Perception, is that "medical science has made such tremendous progress that there is hardly a healthy human left."

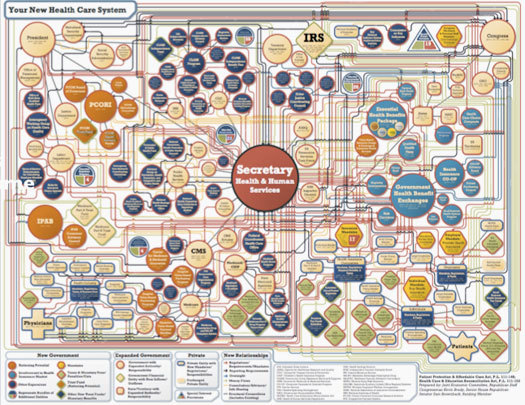

But it's the sprawl and complexity of US healthcare as a system that gives most cause for concern.

The bubbles in that chart (“patients” are the small star-shaped blob at bottom right) describe the $400,000,000,000 that's spent annually on administration, marketing and advertising, lobbying, incomes and bonuses for CEOs, and profits for shareholders in private parts of the system.

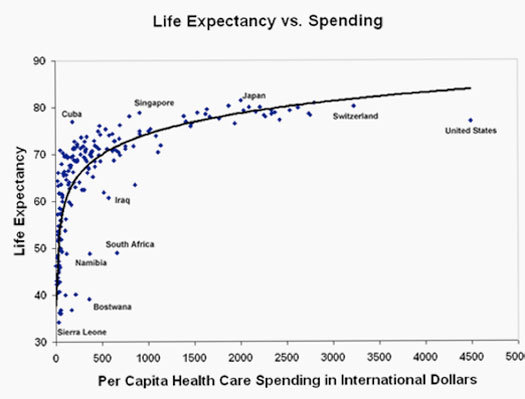

Many medical professionals will tell you that “yes the system is expensive, but we save lives.” This argument would be persuasive if there were no competiton. But medical tourism is eating away at the heart of this vast market. A heart bypass that costs $140,000 in the US can be had for $10,000 in India.

The “we save lives” proposition is also losing traction as evidence emerges, as described by Science in April 2010, that “Cubans achieve the same levels of health with only five per cent of the expenditure levels of Americans.”

If the Meds edifice is built on sand, does the same go for Eds?

Over at Carnegie Mellon University, life seemed to be bustling and self-assured. True, the costs of education are rising even faster than healthcare in the US. True, aggregate student loan debt in the US is now higher than credit card debt. And true, even for well-off families, college education now takes up an enormous and growing percentage of family income.

But CMU's global prestige as a home to 18 Nobel Laureates would seem to be protection even against the fragile state of the US economy. One might quibble that nine of CMU's Nobels were for the “economic sciences” — professions that helped create the global crisis in the first place. But CMU is also strong in subjects such as science and engineering. Even if a CMU degree becomes steadily less affordable for the average American family, there is enough demand for its other degrees, from rich families around the world, to keep the wolf from the door for the time being.

What most exercises Pittsburgh's Eds is not economic survival so much as the danger of a growing disconnect from the city. Eds & Meds contribute very little to the city's hard-pressed finances. The city's hospitals and universities pay no corporation tax; and many of their well-paid staff — all those SUV-driving doctors and professors — live outside the city limits in wealthy suburbs where they don’t pay city taxes, either.

With a population that's declined from 800,000 to 300,000 in just twenty years, the city is financially hard-pressed — but it still feels obliged to bust a gut to make sure that its Eds & Meds feel well looked after.

Design for Resilience

As always, there is a positive side. CMU's design school, and its new head Terry Irwin in particular, seems determined to avoid being stranded in an ivory tower. Although my visit to the city and CMU was a short one, I learned about a impressive variety of projects and activities in the city that contribute more to the resilience of Pittsburgh than high-end Eds & Meds. (My hosts were Gill Wildman and Nick Durrant two British designers who are in Pittsburgh for two years as co-holders of the School of Design’s Nierenberg Distinguished Professor of Design.)

Design professors professors Kristin Hughes and Eric Anderson, for example, worked with Grow Pittsburgh and a local public school on the development of a Learning Lab that would help schools engage students in the seed to table process of food consumption.

Then CMU graduate Christina Worsing told me about the NIne Mile Run Watershed Association.

The watershed once consisted of nine miles of streams that ran throughout the east end of the city. As the city industrialized (and highway-ized) seven miles were bricked, paved, and generally covered over.

This paving-over resulted in enormous damage when rains whipped over the city surfaces, clogged sewer systems, and then got dumped into Frick Park along with trash and debris. The result was the charmingly nicknamed “Shit Crick,” massive erosion, trash, and an almost cancerous ecosystem.

One of NMRW's first major projects was to redesign open streams within the park. Using a pool and whipple system, in addition to tree and shrub planting, they created the foundation for a restored ecosystem that now enhances the park ecologically, aesthetically and socially.

Over ten years, NMR has evolved from a research project into a busy non-profit that's involved in stewardship, urban forestry, rain barrel projects, education and advocacy. NMR now has a staff of 15 who support countless volunteers and work/share programs.

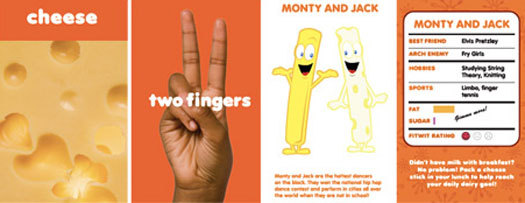

CMU's design school is also involved in a project called Fitwits that is developing health communications and services for schools, doctors’ offices, and family centered community centres. Their “two fingers” portion-control cards (below) are especially neat...

Then from Will Snook, a local web designer, I learned that Transition Pittsburgh is up-and-running. With a commitment to build “Community Resilience in the Steel City,” the group is already running workshops on such topics and permaculture and Shiitake Mushroom Logs; they are also sponsoring a an independent documentary film that investigates the question, “what does it mean to embody sustainability?”

Will Snook, I learned, has also been involved with Small Farm Central, a group of web professionals who provide affordable websites and ecommerce platforms to direct-marketing farmers and Community Supported Agriculture schemes. Small Farm Central provides services to more than 400 farmers across the U.S. and Canada.

Many Pittsburgh neighbourhoods are scattered with vacant lots and unused land that are sitting dormant and in need of development. A programme called Engage Pittsburgh encouraged citizens to reclaim these lots for productive community-use green space. By partnering with existing community garden organizations, sustainability advocates, youth groups, schools, and CDCs, the idea is to develop an organization supporting a network of green sites, community gardens, and urban farms.

There is also the Pittsburgh Garden Experiment — a forum for urban farmers in the city. PGE supports a lively collection of discussion threads, and its members also run classes on such topics as Vacant Lot Remediation. Their work is gaining momentum: the week I was there, Pittsburgh's City Council approved guidelines designed to make sure people and animals peacefully co-exist in city neighborhoods.

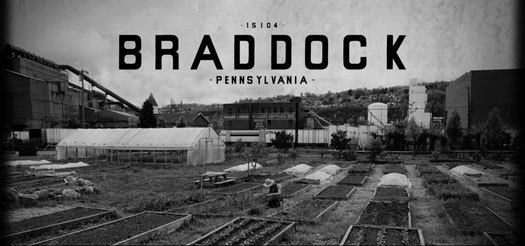

I did not get to visit Pittsburgh's most famous locality, Braddock.

Nor its “coolest mayor in America,” John Fetterman:

But what I did see was persuasive evidence that the Eds & Meds behemoths that bestride Pittsburgh's skyline are not the only game in town. Even a small meadow contains a lot of plants.

It's by no means clear how best design can assist the re-establishment of living systems in post-industrial Pittsburgh — but there's clearly an awful lot of meaningful work to be done.

Comments [3]

That tower is the Cathedral of Learning and it part of the University of Pittsburgh. You've attributed it to Penn, which is at the other end of the state.

04.27.11

11:35

04.28.11

03:47

04.28.11

10:06