Editor's Note: This essay was originally published on July 4th, 2011. While much has changed in the past tweleve years, and the author may choose different links to emphasize her points today, the sentiment is almost more timely.

It was the American novelist William Faulkner who once observed that we must be free not because we claim freedom, but because we practice it. So who am I to take issue with more contemporary interpretations of commemorative form?

A design critic, that's who.

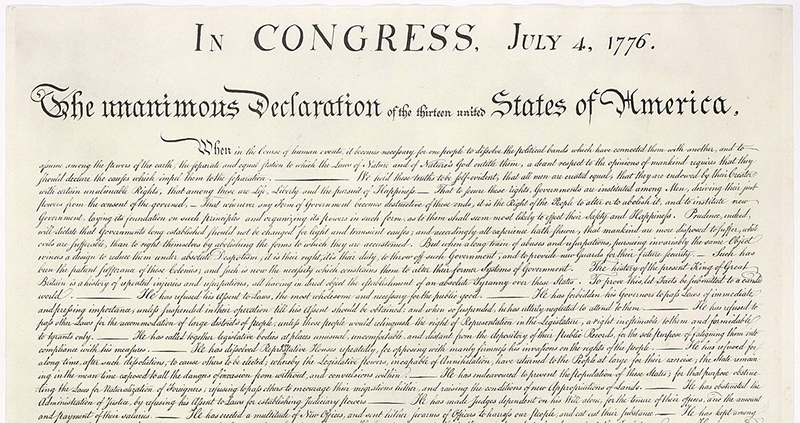

Today, July 4, is Independence Day in the United States. It is for many of us the official start of summer, an occasion marked across the nation by parties and picnics and parades. The trademark red, white and blue colors of the American Flag are in full attendance, and schools, businesses and government institutions are closed. It is cause for celebration, because it is the anniversary of a moment in American history when the signing of a single piece of paper — not a post or a tweet, not a broadcast or a manifesto, but a declaration — established in the clearest possible way the degree to which the States were forevermore united.

To look at the Declaration of Independence even now is to feel something profoundly genuine, deeply impactful, and comparatively primitive. The penmanship alone is redolent of a kind of seriousness of purpose that has rightfully endured, though not, it should be noted, without significant and widespread struggle. Two hundred and thirty five years after the signing of this legendary document, freedom remains imperiled in too many parts of the planet, and the States, though formally united, are not impervious to such issues. It is easy — too easy — to overlook such things here in the land of plenty, where bold advertisements from big-box stores promise happiness through discounted sales — materialistic nudges to remind us that party time is near, and we'd better get moving.

Visual expressions of celebratory joy are in ample supply online, where homespun fonts proliferate. Like Christmas and Easter, these explosions of what sociologists call "episodic time" are made visual (and purchasable) by people who somewhat mindlessly promote the signature colors and shapes that have come to represent these holidays. (And it's not just amateur typographers: think Google and — Hoops and Yoyo notwithstanding — Hallmark.) Freedom of expression suggests that we are all at liberty to say, make and do what we like, which greatly handicaps the critic — and this critic believes that a day like today is perhaps better reflected in thought and deed than through frolicking fireworks and bouncing baselines and goofy artifacts.

The fourth of July is a great holiday, but not because we get a day off, not because we watch fireworks, not because there are picnics and parades. There are wonderful reasons to celebrate, but it is also a sobering moment — a moment that, quite frankly, should invite a hefty dose of humility because we're not really as free as we think we are. Independence does not, in fact, reign supreme. Not even on Independence Day.