Every Building On The Sunset Strip, by Ed Ruscha

A few weeks ago, while reading an enjoyable essay about Ed Ruscha published on American Suburb X, I got stuck (in a good way) on a passage about the creation of his series, and ultimately book, Every Building On the Sunset Strip.

“Ruscha,” wrote Jaleh Monsoor (in what I gather is a piece originally published in 2005, in October), “had begun to develop his own use of the car as a medium,” in 1965:

Ruscha suggested first an elision between the car and the snapshot, and then one between the process of collecting photographs in small books and the process of driving as an act of passage. The car figures in the bookwork as the vehicle enabling the act of photography, as if the car were itself part of the camera apparatus, generative of another means of framing experience.

This led, among other things, to Ruscha “reeling down L.A.’s Sunset Strip and taking snapshots with a now motorized camera attached to his car [or rather, I gather, his “motorized” Nikon was mounted in the bed of a pickup] . … The location of the camera, coextensive as it appears to be with Ruscha’s Ford, rotates from the car’s frontal orientation to its lateral window. … As the car rolls down the length of the street, it produces a series of images of contiguous spaces horizontally aligned.”

Car as medium … rotating motorized camera … a series of contiguous horizontal images of buildings and the street on which they are situated … Did Ed Ruscha invent Google Street View?

I will admit that lately I’ve been mildly obsessed with the “creations” of Google and other digital entities and tools lately. Clearly there’s more than one way that documentation, in the sense of raw and neutral collection of data (visual or otherwise), can result in notable imagery, in a collaboration between creator/artist/designer and machine. Recent examples tend to have the human in this equation sorting through information gathered by an indifferent mechanism or system, and finding worthy images. (See notes below.)

Ruscha in effect forced the neutral info-gathering into existence, presumably sensing some form of worth in interpreting the idea of “documentary” in such a deadpan way.

Or maybe I’m pushing it. But I’m not the only one to consider a lineage from Ruscha’s book to Google Street View: A cursory search finds posts on blakeandrews.blogspot.com and geekglue.blogspot.com — each of which also compares Ruscha’s series Thirty-Four Parking Lots to Google satellite images — as well as a nod in a similar direction in an L.A. Times bit about a street-photography show in San Diego.

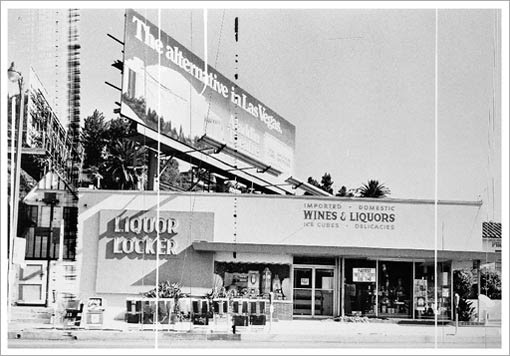

In any case, this Ruscha essay included an image of building Ruscha’s camera-car captured in 1967: A place called Liquor Locker.

From Every Building On The Sunset Strip, by Ed Ruscha (via American Suburb X)

Out of curiosity, I turned to Google. The façade has changed, but here’s the Google Street View now of what I believe is the same spot.

A building on the Sunset Strip, by Google Street View

I’m guessing Google has captured every building on the Sunset Strip several times over by now, producing what you could think of as the equivalent of a cover version of Ruscha’s project. Of course that’s happening by default, a minor footnote to Google’s larger effort to capture Every Building On The Entire Planet.

Additional notes:

1. Interested in snapping a copy of the original Every Building On The Sunset Strip? “My books end up in the trash,” Ruscha once said, according to the Web site of the Metropolitan Museum of Art — which is a fair indication of how far from the trash his books actually ended up. Looks like Manhattan Rare Books can help you out for $7,500.

2. For a bit more on visual-data documentation converted to noteworthiness by way of an artist/author sorting through information gathered by an indifferent machine: It’s Never Summer has a useful and thoughtful overview of work made with Google Street View, and its antecedents, here; and I wrote about uses of online map tools, serious and otherwise, in a Consumed column that is archived here.