Cell Phone Wear and Tear

In the “green room” at a conference a year or so ago, another guy who was going to give a talk abruptly said to me: “Is that really your phone?” He was some kind of Web 2.0 expert, and he had an accent that I couldn’t place, but that would have made me feel inferior, even if he hadn't asked me something blatantly intended to make me feel inferior.

Still, he was on to something. That was, and indeed is, really my cell phone. And, yes, it’s comically primitive by the standards of the smartphone era. There are various reasons that I've stuck with this device, but the main one is that it still works. And I at least trying to use things until they can no longer be used.

In a column in the September issue of The Atlantic, however, I confess the not-admirable flipside of the pious sentiment I have just expressed. Namely, I admit that sometimes I wish my gadgets would die, because that would give me an excuse to buy the next new thing (which quite often happens to be quantifiably better). I argue that in the realm of gadgets, at least, product obsolescence is partly a demand-side phenomenon. You can read that piece here.

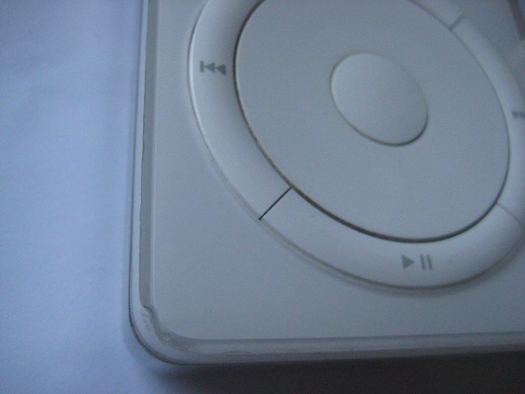

iPod "Classic" Wear and Tear

A spinoff issue relevant to that column, and to my old-phone embarrassment, and to tech-product design broadly (digital as well as physical) is the status of wear and tear. Some objects can surely be enhanced by wear and tear: your favorite blue jeans, my old leather jacket, that particular nightstand, some kid’s hard-ridden skateboard, an obsessively re-read book, almost every building in the French Quarter, etc. Moreover, sometimes an absence of wear and tear is actually detrimental. Consider a carpenter showing up at your house with pristine, unmarked tools. Would you trust this person? Or imagine the self-described outdoorsman whose boots show no signs of wear, or the professed gardener with a glistening shovel and squeaky-clean work gloves: Poseurs, surely.

A passing comment in a FutureLab post earlier this year about “creating emotional attachments to digital objects” at least feints in the direction of trying to apply wear-and-tear appeal to the tech realm:

One idea that a colleague mentioned to me involved the notion of "dynamic weathering" of applications -- the more that you use an app, the more that it would appear "weathered" and used. People would know how often you were reading by how "worn" your iPad's screen looked, for example.

Well, maybe. It's too bad the idea is not pursued any further; this stray thought sounds more like a potential art project than a consumer strategy.

But I like the notion just the same, since it obviously gets at a crucial crossroads: Something designed to be lived with vs. something designed to be replaced. This is not solely a matter for the profession; product-users (or consumers, if you like) have a major say, simply by virtue of the way we value what we use. It's amusing to imagine a demand for the gadget equivalent of "distressed" denim or "antiqued" furniture. For now though, I think visible traces of long and heavy use signal, "Time for a new one."

Laptop Wear and Tear

Mouse Wear and Tear

Lately I’ve become very tuned in to evidence of wear and tear on smartphones, laptops, tablets, and other devices: Scratches, dings, visual suggestions that a thing is a tool with a history of use — rather than a Fabergé Egg fussily dusted and polished, so that its status signal ever shines. On scrutiny, some of the wear and tear actually has a perversely pleasing look to it, to me at least.

Plus it's been instructive to ponder the wear and tear on something like a remote control: on mine, the graphic on the “fast forward” button has worn away completely. What this says about my attention span, the quality of the programming on my DVR, or both, I'll leave to your speculations. In any case, I don't think any of this stuff, stretching back to my (still functioning, but long unused) first-generation iPod, was really designed to accommodate wear and tear. I've simply been slow to replace it.

Remote Control Wear and Tear

First Generation iPod Wear and Tear

While I confess in that Atlantic column to what must be at least partly an aesthetic urge – in short, my craving for “shiny new” things – I also find something appealing in the way wear and tear undermines shiny-newness. I mean that wear and tear undermines shiny-newness aesthetically, but I also mean it undermines that concept almost ideologically, particularly in the context of tech objects. Wear and tear, considered this way, may not result in or reflect an "emotional attachment," but it can feel a bit like a tiny form of resistance: I refuse to buy the latest gadget; I reject your mindless privileging of the new; and yeah, jackass, as a matter of fact, this really is my phone.

(Well, you know ... for now at least.)

See Also:

On the subject of bluejean wear and tear, this 2005 Consumed column explained how a premium denim brand (PRPS) skillfully damaged its product to appear convincingly worn and torn in a manner consistent with the behavior of someone who actually conducts physical labor.

And this 2010 column makes (disapproving) note of Olympic snowboarding uniforms also calculated to appear worn and torn.

Finally, this column addresses tools for what I referred to as digital antiquing, which surely has some connection to wear and tear. There's an emphasis on Hipstamatic, but if I were writing it today I would of course cite Instagram instead.