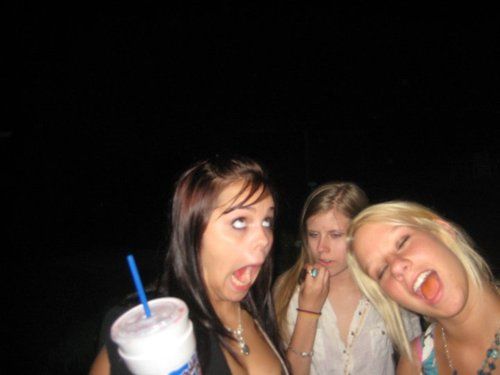

Not everyone is excited about the results. According to Know Your Meme, the photographer who captured this image (is it “you”?) is unknown:

Via Know Your Meme

That’s too bad, because it has become the basis of an image macro known as “Annoying Facebook Girl,” a meme that is often used to comment, in acidic tones, on the mindless documentation of daily banality. For instance:

Via Know Your Meme

Photography is a convenient reference point for considering how digital technology affects not only what we see, but also what shapes the visual dimension of creations across all sorts of media, physical and digital. Earlier in this intermittent series of photography-related posts, I considered a simple tool that struck me as quietly subversive: By reminding “you” of photos taken a year ago, it subtly pushes back against the bias of much new creation-oriented technology, which boils down to make more now. (Annoying Facebook Girl neatly embodies one result of that bias.) Next I considered the arc of human/machine collaboration by noting how Ed Ruscha gave control to machines with Every Building On The Sunset Strip.

This brings us back to “you.” That Guardian piece is illustrated by a Google Street View image. This useful post by It’s Never Summer, “How To Photograph The Entire World: The Google Street View Era,” asked: “Is Street View a camera? Or a repository of source images? Or both?” Maybe the answer is that Street View is a photographer. Certainly the image the Guardian highlights could be considered an example of “something we never could have seen before,” to quote from an essay by Adam Rothstein on Rhizome, positing the rise of “drone ethnography” as a mass phenomenon. “Now, with all of this information at our disposal, it is all we can see. We love this, and we want more.”

So does “you” mean “drone”? As Annoying Facebook Girl suggests, the intersection of ubiquitous cameras and a sensibility that embraces the drone-like documentation of everything in real time points to a future that has ... detractors.

Monkey self portrait, via Tech Dirt

Meanwhile: This summer, a crested black macaque got hold of photographer David Slater’s camera and snapped off “hundreds” of pictures while investigating it, including the rather amazing self-portrait above. Later, Slater said that he gave the monkey the camera to play with on purpose, in the course of defending his claim to hold the copyright on the monkey-made images, an assertion amusingly and convincingly challenged by TechDirt’s Mike Masnick. I’d like to set the legal issues aside and state without reservation that this image might be my favorite new photograph of the year. I think I'd like it even if it were a conventional picture; but knowing that it's the result of an essentially chance interaction between technology and a monkey, I just love it. There’s something here not even McLuhan can be said to have anticipated: We shape our tools, and thereafter … a monkey makes a surprisingly charming image? Perhaps an infinite number of monkeys with Instagram-enabled smartphones could create a groundbreaking museum show. Or at least a kick-ass Tumblr.

A recent essay in Triple Canopy argued “the new photographic aesthetic in formation" that is "arising from a vernacular engagement with everyday technology that barely existed a decade ago,” will be shaped by “compulsive” image-making, and equally compulsive image collecting. As a point of reference, it mentions Garry Winogrand, who left behind 2,500 undeveloped roles of film, and 300,000 unedited images.That's a lot, but it is surely dwarfed by the impossible-to-calculate number of images sitting, unedited, in mobile devices, hard drives, and online services and networks right now.

That piece also asserted that “artists are approaching [new technologies] with the same innocence and fascination as everyone else.” I don’t know about that – innocence and fascination, possibly, but surley not the same innocence and fascination. And that’s sort of the point. And while most of taken by "everyone else" have been made without anything close to artistic intent, it seems inevitable that some are quite good anyway.

Isn't that what's really interesting? Batting away a question about how much film he had to run through before arriving at successful image, Winogrand once remarked: “Art isn’t judged in terms of industrial efficiency.” If it was true then, it must be truer than ever now, as photography (and art, design, creativy) settles into the era of the drone.

Not to mention the monkey.