"Soldier Portraits," at The Columbus Museum (Columbus, GA)

I hope you’ll forgive me for saying something about a photograph taken by Ellen Susan, whose "Soldier Portraits" project I’ve followed unusually closely: We are, I hereby disclose, married.

The thing is, one of her images is about as good as it gets for considering another point in this intermittent series of posts about digital-era photography, this time on the subject of the photo as object. "Soldier Portraits" involves a process (wet-plate collodion, an immediate successor to the daguerreotype) that results in a physical object, a one-of-a-kind image on glass or metal – ambrotypes and tintypes. While she also makes prints from scans, her original ambrotypes are mounted in custom cases (see above).

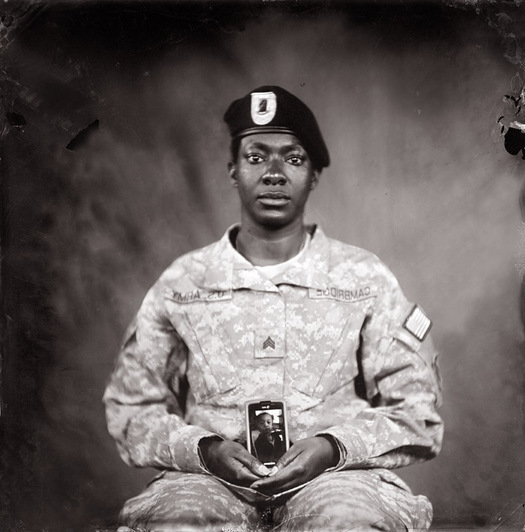

The subjects, from the 3rd Infantry Division of the U.S. Army, are generally asked to bring along a personal item, of the sort they might bring (or have brought) with them on a deployment. On a couple of occasions, soldiers have chosen to bring a photograph — of family members, for instance.

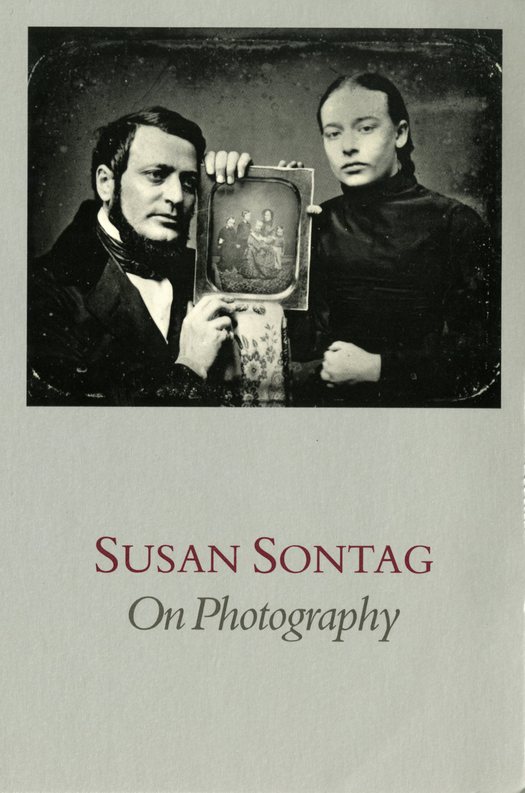

Pictures of people holding pictures have a long history. A random but convenient example: The cover of the 1989 edition of Susan Sontag’s On Photography features a circa 1850 daguerreotype, by an unknown photographer (from the collection of Virginia Cuthbert Elliott), of two people doing precisely this. What better way to communicate our attachment to that peculiar category of object, the photograph?

But sometimes the request to bring a personal object doesn’t quite make it to the soldier, so some improvisation is necessary. Sgt. O'Tarya Cambridge, for example, was (not surprisingly) carrying a mobile phone that (not surprisingly) happened to have, among its data, photographs.

"SGT O'Tarya Cambridge," by Ellen Susan

At The Columbus Museum, in Columbus, GA, "Soldier Portraits" is being shown concurrently with an exhibition of photographic portraits from the mid-19th century, including many ambrotypes and daguerreotypes. Drawn largely from the holdings of two private collectors, it's an impressive array of photo-objects, often mounted in period cases. While the appeal has more than a little to do with their distance in time from the contemporary viewer, that exhibit is titled “Likenesses in the Latest Style” — because of course that’s exactly what they were when they were made: the exciting results of technological progress in image-making. (I gather that title is borrowed from an advertisement from that era.)

A one point in On Photography, which was first published in 1977, Sontag mentions that then-popular Polaroid camera, in producing one-of-a-kind objects, echoes some of the appeal of early photo techniques. But the other appeal of the Polaroid was ease of use, and on that front of course it has been trumped by digital successors, which need produce no physical object whatsoever.

I also hope Ellen will forgive me for dragging her work into this series, since the "Soldier Portraits" project has a good deal more going for it than its indirect connection to my little musings about digital technology. It just so happens that this one piece, "SGT O'Tarya Cambridge," struck me as a kind of essay on the meaningful personal picture, all in one image.

So here, below, is a picture of a photo-object in which the subject holds a likeness in the latest style: a non-object residing in a device that performs numerous other functions. I took this picture with a digital camera, and share it with you now — by way of whatever device you may be using yourself.

Previously in this intermittent series: