From La Joconde, by Mika Matsuzaki and Benjamin Mako Hill

Years ago E and I visited San Pietro in Vincoli, where we jostled for position with a huge pack of fellow tourists to get a look-see at the artwork and relics. Our guided mob reached Michelangelo’s Moses, the main attraction, and the ensuing burst of camera flashes was startling and hilarious. It was as if, we decided, we tourists were actually paparazzi. (“Do you have a comment, Mr. Moses? What was Michelangelo like? And what about God? Over here Mr. Moses! Care to explain those horns, Mr. Moses?”) We didn't take any pictures, but the strange scene remains a fond memory.

Today, obviously, casual documentation of monuments and significant works is exponentially more commonplace, thanks in large part to ever-easier technology for picture-taking, and picture-spreading. The phenonenon can seem absurd, yet it has inspired, directly or indirectly, some very pleasing responses.

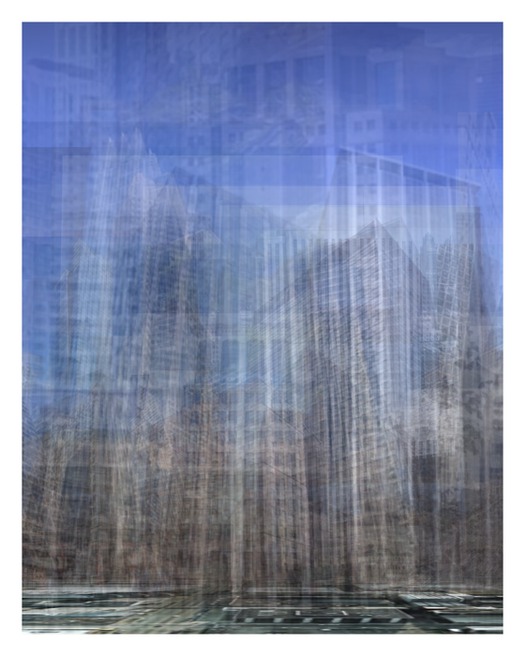

Following an earlier post here about what Google Image searches serve up in answer to queries such as “Mona Lisa,” a reader pointed out to me some work by Jason Salavon, such as the below piece, City (southbound). “In these large photographic prints,” Salavon’s site explains, “the entire Chicago Loop was reconstructed and virtually photographed from typical tourist vantage-points.”

City (southbound), by Jason Salavon.

This reminded me somewhat of images I’d seen earlier (although they were apparently made later than Salavon’s) by Corinne Vionnet. While Salavon's piece above seems to crush together a variety of tourist-friendly images into a sort of time-saving composite, Vionnet evidently collects lots of other images of much-photographed landmarks “via online searches,” and these are “digitally superimposed and stitched together,” according to this Telegraph review, multiplying the time spent on one view of one thing, rather than compressing.

From "Photo Opportunities," by Corinne Vionnet

I’d already been planning to bring up Vionnet’s images in my sporadic series about photography in the digital era. And (in a return to Mona Lisa), I want to connect her work to this project, from Mika Matsuzaki and Benjamin Mako Hill, made up of pictures of people taking pictures of that very famous painting.

From La Joconde, by Mika Matsuzaki and Benjamin Mako Hill

Why do we take pictures of iconic things that are already extensively documented? Surely nobody sees the Mona Lisa and says, “Boy, that’s some painting! I should take a picture of it!” Nobody can think such images will impress or surprise anyone. (“Look at this incredible bridge in San Francisco— it’s called the Golden Gate Bridge!”) Are they worried that they are going to forget what the Grand Canyon looks like?

The camera is a device that “makes real what one is experiencing,” Susan Sontag argued, whether for “cosmopolitans accumulating photograph-trophies of their boat trip up the Albert Nile,” or “lower-middle-class vacationers taking snapshots of the Eiffel Tower or Niagara falls.” Moreover: the “alliance … between photography and tourism” is at the heart of what she called “the predatory side of photography.” We’re still hunter-gatherers, under this theory, bagging images like sustenance.

More recently, I was randomly reminded of a passage from White Noise that seems relevant. It’s a somewhat famous bit about “The Most Photographed Barn In America,” and conveniently, a site called Check In Architecture has plucked that very excerpt and posted it right here. Basically the barn is known for being photographed, and as a result, people show up to photograph it. “Every photograph reinforces the aura,” one of DeLillo’s characters observes. The suggestion here is that we take pictures of much-photographed things precisely because they are much-photographed.

“GPS and The End of the Road,” an essay by Ari N. Schulman, in the Spring 2011 edition of The New Atlantis, adds another wrinkle. The piece cites a number of other writers, most notably Walker Percy, complaining about the problem of pre-familiarity, whether via imagery or guidebook, with a place you’re supposed to see; the example of the Grand Canyon is offered. Schulman argues that GPS, in effect, exacerbates the underying problem: “In travel facilitated by ‘location awareness,’ we begin to encounter places not by attending to what they present to us, but by bringing our expectations to them, and demanding that they perform for us as advertised.” (That’s part of a passage cited with approval by Nicholas Carr on his Rough Type blog, which is where I learned of Schulman’s piece.)

What's interesting about that is the idea that easy-to-use picture-making devices are not the only technology encouraging us to document the familiar. And in addition to tools that guide us to the familar spot and make it simple to re-document it for the nth time, there are always new excuses to collect such imagery — cataloging it in the new Facebook Timeline of our lives, for instance.

From "Photo Opportunities," by Corinne Vionnet

All of which makes me fantasize about a reversal of that passage in White Noise. Imagine a fictional world in which photographing an object actually took a physical toll on it. Perhaps if enough people captured images of the Mona Lisa, the Eiffel Tower, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the original thing itself would break down, fade, blur, become as indistict as a shaky memory, and finally disappear altogether. In that world, Sontag's speculation about the "predatory" nature of photography becomes far more convincing: If you encountered a blurry monument in real life, you would know it must be significant — it's been documented so much, it's hardly there anymore!

The urge to snap a picture would be, of course, irresistible.

From "Photo Opportunities," by Corinne Vionnet

Previously in this intermittent series: