Rob Walker:

At TED, you spoke about the way that algorithms — math, machine language — influence the world we see, in ways we don’t always understand, but that we need to. In the “Talk To Me” essay, you argue that the current vogue for “augmented reality” is drastically misguided. Is there an intentional connection between these two arguments? I want there to be a direct line.

Kevin Slavin:

There’s not a direct line. But they both derive from some of the things that led to Area/Code. A couple of examples: Back in the late 90s, early 2000s, Geocaching was just beginning, and a couple of years later, Katie Salen, Nick Fortugno and Frank Lantz did the Big Urban Game. Around that time, maybe 2002, the anti-war demonstrations were happening, and I watched a bunch of protesters shut down Broadway at Prince street — by basically holding hands across Broadway. I was thinking: “This is not going to end well.” As I watched, though, there was this moment when the protesters looked at each other and suddenly dropped hands, shed a layer of clothing, and melted into the crowd. I realized they all had earpieces, and they were plugged into a grid that was better than the NYPD’s. Two minutes later, the police arrived, but it was already long over.

When we started Area/Code in 2004, it was “software for cities,” and we were interested in entertainment software. We were working through certain curiosities about how, on the one hand, these new technologies affect how individuals interact with the world, and then on the other hand, how these larger collective organisms called cities are also reshaping themselves around software. And in a long indirect way, those two questions led to these two talks.

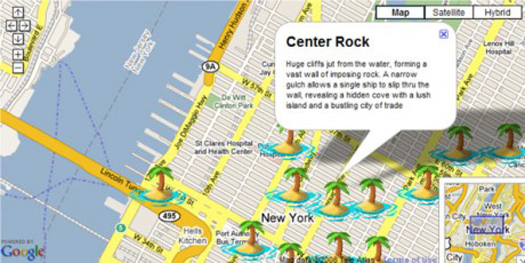

Plundr, by Area/Code (2006), a location-based pirate adventure game that “locates the user’s computer in physical space and uses their location as part of the game.”

Plundr, by Area/Code (2006), a location-based pirate adventure game that “locates the user’s computer in physical space and uses their location as part of the game.”RW: Maybe you could walk me through how the algorithm talk came about.

KS: I’d been interested in algorithmic trading since meeting an Israeli algo trader in 2005. He’d explained, among other things, how his own firm’s algos were under attack by other algos. Six years ago that felt like proper science fiction, but that’s the least of it. The most interesting aspects for me were the dynamics of communications latency and arbitrage, about the ways that network topology was literally forming urban topography. So I gave a very early version of the presentation in January of '10, at Microsoft Research's Social Computing Symposium. The theme was “the city as canvas.” That talk was about weaving together the history of speed, information, war, finance and urban topography, all to make the point: Yeah, the city is a canvas — but who gets to paint it?

By chance, two weeks later one of my students at NYU told this story about the day his father quit his job, as a radio DJ, in a small town in Maine. Basically, the station manager handed him a computer printout with a list of songs on it and said: “This is what we're playing today. Sales figures came in from the point-of-sales systems and these are the songs the computer says we're supposed to play."

I realized that the story wasn't just a finance story, not just a city-as-platform story. It was the story of how algorithms are structurally embedded in all these other aspects of everyday life. The premise behind algo trading is also the premise behind algo culture as a whole, which was starting to show up everywhere I looked ... the Netflix Prize, Destination Control elevators, the guy at Princeton who figured out soil algos to price wine better than Parker. And right then a computer won Jeopardy.

KONE destination control system: “offers passengers a user-friendly destination operating panels (DOPs) in the lobby rather than the elevator car.”

So I did a new presentation at LIFT, in Geneva, and a shorter, revised version of that became the TED talk. The point is we’re using algos to analyze the world, but it goes beyond that: we've weaponized some of them, so they're not just thinking, they're acting. For me, it's not about the finance piece. That's just the visible apex of the thinking and practice. I really do believe that as surely as we had a flash crash on Wall St, we can have them in culture if we're not careful. And the first way to be careful is simply to understand that there's something to be careful about.

RW: And that “something to be careful about” involves the sort of creeping prevalence of algorithm-made decisions?

KS: That’s part of it. I’ve lived my whole life in New York City, so I’ve always been obsessed with why things are the way they are in New York. What’s interesting is that when you trace them, most of the reasons were generally around the needs of people and the stuff they did, like move crates from ships, or take trolleys. But if you look at how a lot of things are being shaped now, the criteria have nothing to do with humans. That’s weird.

I think about this every time I go to the airport. I check in on my phone, and it produces a code, and I go to the airport and hold up something that’s designed for a machine to scan, and that’s my ticket. At the same time, I’m presenting information to a person, to prove that I’m me, and really, they have a list of everyone who should be on the airplane. So what am I really doing? I’m transferring like eight bits of data on a screen, carrying it from my home to another place, so a computer can authenticate a connection. It’s like a sneakernet approach. It’s helping a computer speak to a computer; you’re just the messenger.

A while ago I was buying beer from Tesco in London. It’s all self-checkout. So I scan the beer and it gives an error. And the guy who works there comes over and holds his hand up, and sure enough he has a barcode stuck to the back of it... he scans the back of his hand and says, “Now do it.” The upshot is: he was verifying I was old enough to buy a beer, but he has to express himself in barcode so that the machine can sell me the beer.

There’s a very gross version of what I’ve been talking about — the BBC has kind of seized on it in an article loosely based on the TED talk, and they take my phrase “shaping the world” and replace it with “controlling the world.” That’s not what it’s about at all. My concern is not that the machines are going to become so smart. My concern is that they’re actually kind of dumb, and they require us to accommodate them. And that we do.

RW: I guess this happens by degrees. I would have said it’s good not to have to the paper ticket, because I’m just thinking of the immediate precedent.

KS: It’s hard to reengineer the whole system. Mostly all you can do is patch. And where we can’t modify the system, the patches are behavioral.

Like this: when I’m talking to a voice recognition system, and it’s telling me to say “Yes” or “No.” I find that I’m saying “Yes” in this way that isn’t speaking to be understood by a human; I’m speaking to be understood by a machine. The machine is basically making a concession by allowing you to speak human, and you’re making concessions to speak in machine dialect. You have to imagine how a computer wants to hear you, to make yourself understood.

We are learning, all of us, how to speak system. You know what a good example of this is? Writing for SEO. Demand Media and The Huffington Post are built around that. What are you actually doing when you write for SEO? You’re no longer writing to communicate clearly with a human. You’re writing to be as clear as possible to Google search algorithms. It’s creating a kind of writing that kind of denigrates language. But, it makes perfect sense; with SEO-driven sites, their audience isn’t an idealized human reader, it’s an idealized machine reader — which has quantitative criteria. A friend of mine mentioned it recently — it sounds bad to say this — an algorithmic approach to English is basically Newspeak. It’s a way to parse language precisely, in unambiguous terms, without the subtleties and vagaries of genuine human speech.

Monocle, Yelp’s augmented-reality manifestation, via CNET.

RW: So what about the “Reality Is Plenty” essay, where did that come from?

KS: “Reality Is Plenty” started with just being unhappy with the way things are going. I used to go into ad agencies in 2004 and talk about augmented reality, and they’d say, “What are you talking about?” And that is so preferable to having all of them call me in 2011 and say, “Yeah we really want to do some augmented reality.” So when I was talking to Paola Antonelli about “Talk To Me,” I said, “I just hope there’s no fucking augmented reality in the show, because I can’t stand it.” And that conversation led to the essay. It’s not that there’s nothing good that come out of AR. But there’s a faith in it that I find unnerving.

RW: A faith?

KS: Faith that it will make the world better, and more exciting. As if it will solve a lot of problems that aren’t problems. Yelp was one of the first to integrate augmented reality into its app, so you could hold your phone in front of you, and whirl around, to see what direction the laundromat was in. That is so much more difficult than simply looking at a map. So, yes, it’s possible to find something with AR, but is it better? No, it just isn’t any better.

Given everything a phone can do, suggesting that the screen is the most important thing about it seems like a misunderstanding of what’s powerful in there. For me, the single most powerful aspect of the mobile phone is that it’s connected to other people and other things. I’m not saying the screen isn’t important. But what makes the screen of the phone powerful is that you can look at anything, anytime — not just what’s in front of you. What’s in front of you is already in front of you. Being able to gather information about what’s in front of you is what we do all the time anyway. We’re either using data on our phone to connect with somebody we know, or to connect about something that we’re thinking about, or to connect about something that presents itself to us in that moment. And none of those things are made better by overlaying an informatic layer onto video.

But AR, because it’s difficult, because it’s clever, and because it’s now available, has had this kind of fetish quality to it. It makes me sad because there’s so much effort that goes into it that could be going into other forms of real magic.

There’s an app that two former students of mine did, called Crow’s Flight. Simple and brilliant. You put in an address, and it uses a compass and just tells you, “It’s three thousand meters in that direction.” That’s much better. That makes sense.

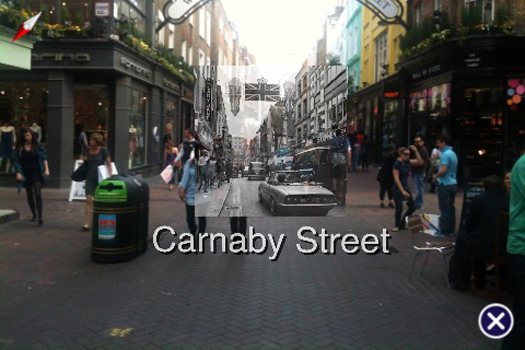

A StreetMuseum augmented-reality image from Creative Review.

A StreetMuseum augmented-reality image from Creative Review. RW: The augmented reality projects that I’ve found clever or interesting really aren’t about finding your way around, or even about efficiency, really. Streetmuseum is about historical images of wherever you happen to be. And Museum of the Phantom City is a sort of geographic guide to utopian visions that never came true. Those seem like clever uses of the technology to me.

KS: I guess. I know some of the people involved in Museum of the Phantom City, and they’re good people. But, in order to see the things that they want to point out, I have to go that place — well, okay. But then, once I’m there, the best way to display that information is the juxtaposition of it in front of what I’ve just traveled there to see? I don’t think so. Bottom line, maybe, is that visualizing the invisible is difficult, and might not be best expressed through the metaphor of the camera.

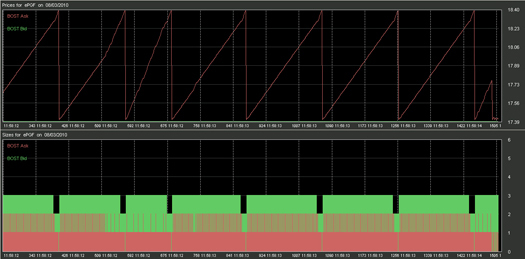

“Boston Shuffle”, algorithm-driven trade pattern identified by Nanex: “1250 quotes in 2 seconds, cycling the ask price up 1 penny a quote for a 1.0 rise, then back down again in a single quote (and drop the bid size at that time for a few cycles).”

RW: In the TED Talk you mention that company that gives names to trading patterns it’s identified, like the “Boston Shuffle,” which strikes me as an attempt at something that looks like accuracy and efficiency. To come back around to Area/Code, you’ve said its projects aimed to evoke instead of inform; move toward “deliberate distortion,” not accuracy. Is that the key tension now — “deliberate distortion” vs. accuracy?

KS: Those goals aren’t necessarily at odds. When humans navigated by the stars, there was no way to process the endless array of data that is the night sky. You can be clear that you're looking at the same stars as yesterday, or that they move across the sky in certain ways. But to make them legible, you need to give them names and stories — like Gemini, like Cassiopeia.

Now we use lat and long for navigation, we use telemetry coming off satellites, and we use routing that's derived from, yes, algorithms. But these new forms of data don't have stories. So we’re making them. Without Nanex providing us with the names and images of the market, how would we be able to imagine it? We make stories to understand the world. If they’re fictional, like the stories of the zodiac, that doesn’t make them any less important for sailors in understanding where they were.

But — and maybe this is what you’re getting at — what spooks me about algorithms as nature is precisely that they have no distortion, they have no affordance, there's no purchase on the world they describe. Their illegible nature is, quite literally, a world without narrative. There's only a beginning and an end.

What's important to me about the kinds of things we were doing with Area/Code — and all the designers around us — is that we were building systems in the middle of the data, some systems that gave us a way to read, and reasons to read it. The stories we were telling with locative games were fiction, but as always, good fiction describes the real world rather precisely.