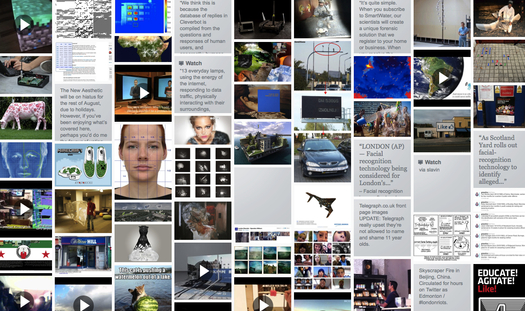

The New Aesthetic, partial archives

Many of us grapple with the impact of screen culture — or digital culture, or whatever you want to call it — on the way we see the world and the things that are in it. (That’s distinct from the way the world looks to us, which I think of as, in effect, the result of the way we see, or perhaps merely look at, things). One of the more addictive responses I've encountered to this line of interest is James Bridle’s online effort, “The New Aesthetic.”

Bridle is a partner in The Really Interesting Group; his numerous and varied projects include The Iraq War Wikihistoriography (a set of 12 bound volumes documenting every change made to the Wikipedia entry for “the Iraq War” over a period of five years), and he writes often about “book futurism.”

One of the things that makes Bridle’s Tumblr so addictive is that it’s relentless. Example after example piles up, and I can’t disagree with any single one — but somehow the volume confuses things for me. I approached him thinking that asking a few questions about his attempt to capture a “new aesthetic” might be a step toward clarifying stuff I’ve been reading, and sometimes writing, about. Here’s our back and forth.

Q: In your introductory post back in May, you described this “new aesthetic” by saying “we need to see the technologies we have with a new wonder. … Consider this a mood board for unknown products.” Among those reacting, Robin Sloan wrote: “I think it really is something distinct, something you can sort of get your arms around—not just, you know, a bunch of cool-looking stuff.” I want that to be true, so I’m trying to get my arms around it. Do you feel your definition of what you’re up, and what the goals are, has shifted? Gotten narrower? Broader? In short: What have you learned?

A: I'm not sure I've learned anything more, so far, than that there's a lot of this stuff out there, and I'm not the only one who feels it. Despite such a weak name, the term has struck a chord with people, and I receive frequent emails and tweets from people saying "Is this...?" or even "I think this is New Aesthetic..." I still use my own fuzzy judgment on what to add to the Tumblr collection, but I agree with them more often than not.

The definition was incredibly broad, and I like disappearing off down different tracks for days at a time, whether that's autonomous military drones, financial algorithms or the perceived psychology of spam comments. At weekends, there's frequently a focus on art, whether that's David Hockney's time-bending film work, or animated GIF collages.

There's usually a visual focus to the Tumblr, because it is after all a Tumblr — a mood board, as you note. There's thinking going on behind the images, but I rarely comment on them directly, because I like to see how other people tie them together. But as more people react to them, particularly designers, I can feel myself digging deeper into what fascinates me here; after all, I am not a designer. People like Matt Jones are doing a lot of work on the visual aspects of the New Aesthetic's "robot-readable world" and the increasing number of ways in which computer vision shapes the way we see things. Likewise, I started exploring high-frequency trading before coming to the work of Kevin Slavin on the algorithmic macroscope.

Stumbling into other peoples' back yards is good, as it helps to define one's own territory. I'm realising I'm more interested in the communicative and psychological effects that living with these technologies produces, the cross-fertilisation between technology and culture and the normalisation of those cross-overs—as well as the sheer temporal vertigo it can produce.

Q: I see that you're planning a panel for SXSW, and the description there was helpful: "Our devices are learning to see, to hear, to place themselves in the world." One of the questions I gather the panel will address is “ How do these senses change the way we see the world, and how should we design for it?” Can you point to something in your own work that’s been productively influenced by understanding the new aesthetic you’re talking about?

A: I'm not sure about productive influence, but several recent pieces of work have spun off from the New Aesthetic as I try to understand it more, both its effect on me, and on the wider world.

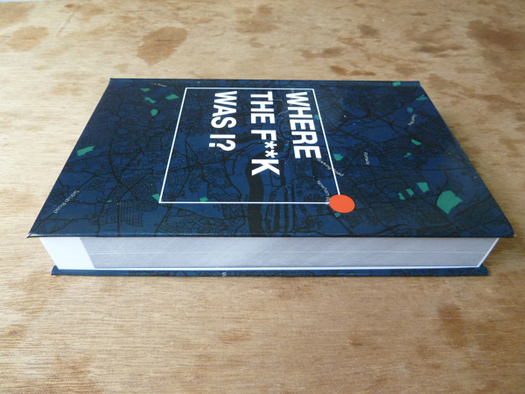

Where the F**k Was I?, James Bridle

Where the F**k Was I? is a book of maps I made from the 35,801 location records stored on my phone between April 2011 and June 2010. These were the records that created a mini-scandal around the iPhone earlier this year, when it was revealed that the device was storing this data, unencrypted, without the user's knowledge or permission. This data represents not my actual or remembered location, but the device's own perceptions, cross-referencing me with digital infrastructure, with cell towers and wireless networks, with points created by others in its database. An atlas drawn by robots.

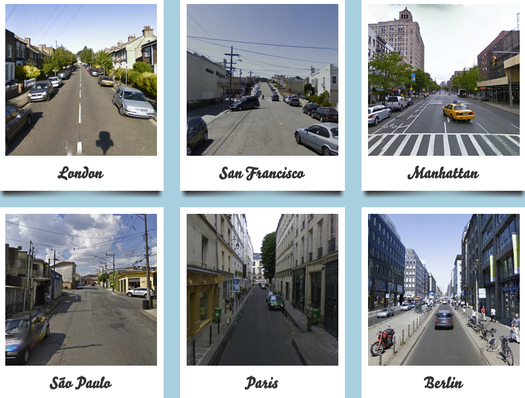

More playful explorations of ways of seeing have included Robot Flâneur, an attempt to humanize Google's all-seeing eye, and Rorschmap, a re-rendering of digital mapping technologies.

I'm also really interested in the physical traces of invisible networks, particularly datacenters and network access points. In a recent article for ICON magazine I examined the idea of "the cloud" and the aesthetics of datacenters in the context of civic architecture and digital industry. All of these concerns surface in different ways in the New Aesthetic.

The New Aesthetic is not criticism, but an exploration; not a plea for change, rather a series of reference points to the change that is occurring. An attempt to understand not only the ways in which technology shapes the things we make, but the way we see and understand them.

Robot Flâneur, James Bridle

Q: I’m interested in your question: “What does a machine-readable world look like?” That makes me think of The Nine Eyes of Google Street View, for example. Is it your view that the machine-readable world coexists with the one we see when we simply walk around, with no screen or processor between the eye and physical reality? Or is the world you’re talking about replacing that world? Is the job of the designer or the artist or the critic to reconcile the two — or to cope with the possibility (certainty?) that one has effectively obliterated the other?

A: 9eyes was definitely a big influences on the New Aesthetic. I'm intrigued by the way these apparently senselessly-collected images create meaning and facilitate a kind of farsight. Robot Flâneur was obviously one outcome of this: a dérive through a world as seen by robots. Google Sightseeing and the somewhat uncomfortable Doxyspotting are other iterations of the same idea.

Artistic responses to Google Street View have been numerous as well, whether it's Michael Wolf's dramatic "A Series of Unfortunate Events" or the landscapes of Doug Rickard's "A New American Picture.” These artists are attempting a reconciliation of the kind you describe; while maintaining the artist's role in the process through selection and framing.

Rorschmap and Robot Flâneur are more systems than artworks. With an emphasis on interactivity and randomness, the role of the artist is more obscure, facilitating a connection between image and viewer, rather than attempting to mediate or control what they see. A framework for reading the robot-readable world.

So, to some extent, the machine-readable world, where the tools of that reading are senses that we share (vision and hearing, primarily), is one that we inhabit, too. But reading is not mere apprehension, but a cognitive process acting on that apprehension, and computers think very differently to us. So aspects of this world may be perceived very differently. Google Street View's images alone are meaningless when they sit unexamined in a database, but when we look at them we create meaning. Somewhere, an algorithm is doing the same thing, to different ends.

My background and much of my professional work is in publishing, particularly digital books and digitization. I've written before about some of the stranger aspects of this, and digitization, I increasingly feel, is one aspect of the robot-readable world. As we turn physical media—photographs, music records, books—into digital artefacts, we don't merely translate from one medium to another, we render them readable by computers, by algorithms. The question arises: who are we doing this for? Bernhard Rieder calls these artifacts "data objects," things which can be acted upon computationally, in turn producing what he calls “computational value”. We need to think carefully and clearly as to who or what this value accretes.