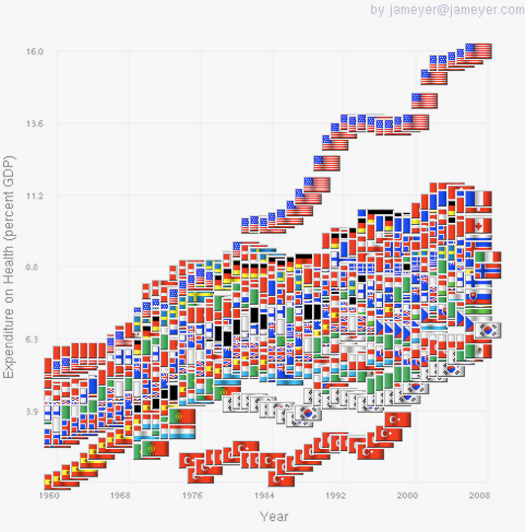

It's easy for two people to look at the same information — such as this chart (above) about health costs — and perceive totally different things. What I see is an out-of-control Medical Industrial Complex that's heading, Icarus-like, for collapse. What many designers see is a sea of opportunity — and boy do they want a piece of that action.

They are not alone. Many city-regions see the “health space” as an opportunity for growth. In the Netherlands, for example, Groningen's Healthy Ageing Campus is billed as a “research and entrepreneurship zone” that will focus on healthcare, food & health, medical technology and pharma.

In Eindhoven, too, a project called Brainport Health Innovation (BHI) will focus on “well-being for the elderly and chronically ill…while generating economic opportunities for the region”.

The pattern is Europe-wide: an organization called Healthclusternet is encouraging all the EU's 27 member nations to develop “regional health systems and health innovation markets”.

The promise of economic opportunity persuaded its sponsors to pay for last week's World Design Forum in Eindhoven on the theme of “Creating a Caring Society”.

Eindhoven, home of Philips and the lightbulb, was recently voted “smartest region in the world” for its prowess as an innovator of high-value, technology-based products. A meeting to explore how this smartness might be applied to the global care market must have seemed a promising idea.

The only problem? Our discussion raised the possibility that a complex, doctor-intensive, technology-based approach may not be an affordable, or even necessary, ingredient of caring society.

My contrarian advice was that we need to grow care systems based on five per cent of the costs per person that we have now. This sounds like a fantasy, but is not. In Cuba, for example, where food, petrol and oil all have been scarce for of 50 years as a consequence of economic blockades, its citizens "achieve the same level of health for only 5% of the health care expenditure of Americans."

The use of Cuba as a benchmark is a hard sell at health industry events. Imagine my surprise in Eindhoven, then, when a Cuban-style strategy was advocated by someone with real financial clout. Roger van Boxtel, CEO of a big Dutch insurance company, Menzis, used this (admittedly hideous) upside-down pyramid to describe how his company plans to re-direct spending for its two million insured clients.

The tiny triangle on top of the right-hand pyramid — marked "soon" — represents pretty much the entirety of resources for today's Medical Industrial Complex. When I asked the head of a huge hospital, on the same panel, what he made of this startling transformation in resource allocation, his rueful reply was that “if he says so, that's the way things will go”.

Menzis does not propose to do away with hospitals altogether. But it does intend to reduce costs radically by focusing common procedures at a small number of preferred suppliers. It will send all patients for hip replacement, for example, to one clinic, Maartsenkliniek, which already performs 700 hip operations a year.

Logically, it is hard to see why Menzis' inversion of the Follow-the-Money principle should stop at Dutch borders. An international patient visiting India can save 70 to 80 per cent on the average cost of similar procedure back home. Hip replacement surgery at the top rated hospital in India costs US$5,000 — including the cost of an FDA approved implant or prosthesis.

Departure Lounge

Medical tourism to India is not the kind of patient journey that intrigues designers — or at least, not yet.

In Eindhoven, our jaws dropped at a gorgeous presentation, by Paul Priestman, of his Recovery Room of the future. Priestman drew on his expertise as designer of Lufthansa's first class cabin to argue that hospitals do not have to be clinical, inefficient and unwelcoming.

Lufthansa-quality recovery lounges in hospitals would of course be lovely — but they are unlikely to reduce the cost explosion in health. The cost to an airline for a ‘super first class’ model, with its 600 parts, can reach $160k [114k euros] per seat. When you consider that only five per cent of the world's population has flown on an airplane at all, let alone in first class, high-end Recovery Lounges look likely to remain a niche market.

To be fair, Priestman was adamant that design quality in hospitals does not have to be ruinously expensive. His firm has also designed 50,000 hotel rooms for a hotel chain within a much tighter budget per-bed than in a new hospital. But if Roger van Boxtel's cost-reducing strategy is where things are headed, the design opportunity concerns a radically different kind of patient journey.

Care: The Social Space

A key principle of Cuba's system is that health and wellbeing are not something ‘delivered’, like a pizza, by distant suppliers. In Cuba's — and Menzis' — version of a caring society, value is created by mutually supportive relationships between people in a real-world context, away from big medical institutions. This is no small shift of emphasis; the 'delivery' metaphor is pervasive in the developed world's systems.

That said, Cuban-style 5% health is not about a u-turn back to a pre-scientific age. It's about focusing resources and creativity on the 95% of care that happens outside the medical system already, today. It’s about re-imagining the 'health space' as a social and ecological context which, like a garden, needs to be cared for — collaboratively.

Dementia Challenge

Welcome signs of a care-as-ecosystem approach are emerging in the UK. The Department of Health and the Design Council are running a competition to rethink life with dementia. The stated objective of this 400,000 euro ($580k) challenge is "to get new solutions up and running and into the hands of the people who need them".

The UK project, dangling an economic carrot to encourage partipants, describes the baby boomer generation as "a large group of sophisticated consumers looking for products and services to support them in their later years". But the 16 service ideas shortlisted are relatively low-cost, low-tech and people-focused solutions that are unlikely to excite a red-blooded VC. They include online and physical tools for better collaborative care between relatives, friends, and professionals. A web-based service would help carers find part-time work, and people with dementia contribute to society. A service to facilitate daily journeys for people with dementia is envisaged. A volunteer network would locate and safely return people with dementia who wander is described. There's a website and peer-to-peer platform for carers to deal with diagnosis and planning.

The Design Council's shortlist does include the odd high-tech gizmo, such as a wristband for monitoring the location of people with dementia that includes 3D accelerometers and RFID. But the tech component overall is at the service of social innovation, not its driver.

The Design Council also promises entrants "100% ownership of the intellectual property rights to your idea". But even that remnant of old-paradigm care-as-business thinking is easily surmounted: Most the tech-enabled functions described in the shortlist already exist as open source applications in Pachube.

Care Co-Ops

One of the main reasons industrial world health systems are unfit for purpose is that they under-value socially-created knowledge and socially-delivered support. This is why open source health, and learning how to create and grow care co-operatives and other forms of care collaboration is so important.