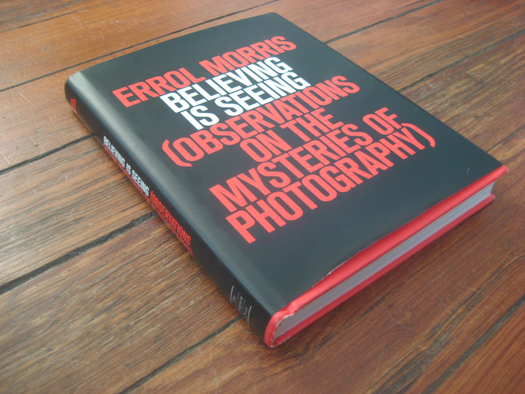

Believing Is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography), by Errol Morris

It’s the “of the year” time of the year: a few weeks spent naming the best books or music or music films, or the most significant events or people, of the year.

As a reader I enjoy this mini-season, an annual excuse for me to (silently) disagree with everyone else’s lists. As a writer, I tend to avoid it. But this year I’m making an exception, because for months I’ve had a pretty good idea what I would choose as the “image of the year.” And for reasons that will become apparent, I’m going to cast my vote for book of the year, while I'm at it. But I’ll get to that.

The image of the year, hands down, is the image of Osama Bin Laden, dead. I haven’t seen it of course, and unless you have fairly rarified security access, you haven’t either. That’s why it’s the most compelling image of 2011: At this point, there’s nothing more surprising, and fascinating, than an image people might want to see, but can’t.

After all, we’ve all observed the long-term shifts that surely made 2011 the most image-soaked year of all time — and that will make next year, and the year after that, even more so. Cameras and video recorders, built into various other devices, are increasingly ubiquitous; space for storing them online is basically limitless. Grotesque evidence of a despot’s violent death and all manner of other corrosive images are just a click away, and sometimes difficult to avoid. Surveillance (by security cameras, by drones, by Google's roving Street View cars, by average citizens) is routine. And so on.

So when news of the Bin Laden killing was accompanied by calls from many quarters that images of his corpse needed to be shared with the public, I assumed that it would happen promptly. An interesting question is why people wanted to see those images. The official answer is that it would provide proof. But the explosion of images has been accompanied by an explosion of doctored, faked, manipulated, and overtly remixed images. It's also been accopmanied by the apparent deterioration of any given image’s authority.

Which brings me to my book of the year: Errol Morris’ Believing Is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography). The book is not about digital-era image culture, but it’s vital reading for anybody interested in photography as "proof," or really photography in general. Over six chapters, Morris examines photography, and how we look at it — what we project into images, sometimes including even the intentionality of the photographer, or the morality of the subject. We see things that aren't there, and miss things that are. “Our beliefs,” he argues in a pivotal passage, “can completely defeat sensory evidence.”

While Believing Is Seeing is a collection of essays, I hesitate to call it that, because the words fail to capture what's so distinct about Morris’ approach. In each piece he’s on some kind of quest to answer a question, but also, really, to make a point. He interviews experts to whom he is led by his own curiosity, and instead of synthesizing the results, he gives us long, verbatim back and forths, with digressions, equivocations, disagreements. He includes moments when his research dead ends, or contradicts his own hunches. He also gives us lots and lots of visuals.

And when he does transition into his own voice, his conclusions have more force, precisely because he has walked us through the evidence he has obsessively gathered and considered. Derived from material Morris first presented on his New York Times blog, the pieces in this form add up to some sort of new genre – investigative criticism, maybe.

Obviously the Bin Laden images don’t come up in Morris’ book. But I thought about (or imagined) them while reading it. By then I felt pretty certain that, contrary to my initial hunch, those images would not be made public any time soon, if ever.

Now I wonder, if they do surface, how they will be interpreted. If it happens, I hope Morris weighs in.

Previously in this intermittent series about photography: