#29.942566, New Orleans, LA. 2008, 2009

#34.546147, Helena-West Helena, AR. 2008, 2010

#39.259736, Baltimore, MD. 2008, 2011

#39.777110, Camden, NJ. 2009, 2010

#40.805716, Bronx, NY. 2009, 2011

#41.779976, Chicago, IL. 2007, 2011

#82.948842, Detroit, MI. 2009, 2010

#83.016417, Detroit, MI. 2009, 2010

The titles of the pictures were carefully considered and contain three pieces of information. The first number is a Google code that contains geographical (possibly GPS) coordinates, but has been modified by Rickard so as to not disclose the exact Street View location. Second, is the name of the city and state. Lastly are two dates. The first date refers to the year the photograph was taken by Google Street View, the second date refers to the year that Doug Rickard made his picture. The overall title is meant to resemble an American street address and tie into location without specificity.

“What's in store for me in the direction I don't take?”

— Jack Kerouac

Doug Rickard, the son of a retired preacher, grew up learning about America from a decidedly slanted point of view. His father, a Christian conservative who led a mega-Church in the 80’s, was highly patriotic and proudly part of the “Moral Majority.” He taught his children that America was “the exception to the rest of the world” — that God had anointed our country as “special and unique.” This patriotic but misleading Reagan-era dogma may have been inspiring to most in the congregation, but young Doug, very much a rebel in his youth, had nagging doubts.

In spite of his troubled youth, Doug would graduate from high school. He then took a break of five years before attending college. In retrospect he sees the break as crucial and “one of the best things to occur,” as he could not have been “ready to learn” until that older age. It was through his studies in history and sociology at the University of California, San Diego (History major, graduating in 1994) that Rickard began to compare the greatness of our country with an unsettling truth: that America had a very dark past — a key being the enslavement of Africans to be a workforce for the American South. Deeper studies into the periods of segregation, “Jim Crow” laws, and the Civil Rights movement would impact him greatly.

Rickard, an artist as a child (his teachers would exclaim to his parents that he would surely “do something special” with his artistic talent), discovered photography in adulthood — a discovery that would become an obsession. He began to codify this obsession in early 2008, when he created the now highly popular websites American Suburb X and These Americans. These sites, largely extensions of his personal journey, obsessions and self-education, are now highly regarded by photography aficionados, educators and historians for their high quality of writing and massive visual archives. ASX receives approximately 80,000 unique visitors a month and is “Liked” by 38,000 Facebook “fans.” These Americans is known in part for being a view into Rickard’s personal found-image archive.

With such a strong interest in history, Rickard was used to looking at the past. But for these new web projects he turned his attention to the present, exploring the statistics, demographics and socio-economics of contemporary America’s neglected communities. While doing this he began to experiment with ordinary and static images resulting from keyword searches on Google. But by the next year — in mid-2009 — he discovered Google Street View.

In a telephone interview that lasted well over an hour, the 43-year-old-old Rickard told me that the idea for his recent photographic work emerged as a sort of “epiphany” within 24 hours of using Street View. The project was, he explained, the result of a sort of “perfect storm,” in that it combined his love of photography and its history with his background in American history and sociology. Also, practicality was a component in the form of his inability to travel America, a restriction of the scenarios in real life — a demanding day job and a young family. According to Rickard, this epiphany fused immediately into a crystal-clear idea: He would use Street View as his camera and, working from a room in his home, travel the roads of neglected American cities and neighborhoods in a 21st-century “road trip.” This single idea would utterly consume his life for close to two years, resulting in the important body of work “A New American Picture,” a selection of which hangs today in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

When Google launched Street View in 2007, it was the company’s intent to map and document every street in the United States. Cars were dispatched into every city to drive every street and back road, using nine directional cameras mounted on the roofs of special cars. These cameras give us 360° movable views at a height of about 8.2 feet. There are also GPS units for positioning and three laser-range scanners designed for measuring up to 50 meters 180° in the front of the vehicle. Rickard analyzed tens or hundreds of thousands of Street Views in his search for perfect pictures, something he describes as containing an “apocalyptic-like brokenness.” Indeed, the height of the camera at 8.2 feet, while creating an aesthetic cohesion and uniformity of vision, adds a distinct feeling of “alienation” that Rickard employs. Unlike the making of street photos in the traditional sense, with Street View there is an oblivious-ness to the camera as it goes about its job with no feeling or emotion. In spite of this anonymity of machine, his images are — perhaps surprisingly — layered with empathy.

Rickard has amassed several terabytes of Street View images — nearly 15,000 shots captured, labeled, and stored. From that massive stash, he selected only about 80 images for “A New American Picture,” of which a selection is on view at MoMA. To give you an idea of the voracity of Rickard’s Street View search, he has virtually explored almost every neighborhood in the “broken” portions of Atlanta, New Orleans, Jersey City, Durham, Houston, Watts (in Los Angeles) and Camden. He has also explored, inch by inch, the smaller towns of America with names like Lovington, Waco, Artesia, Dothan and Macon. What he looks for are images that carry what he calls a certain “poetry” of subject matter, color, and story — a story described in part by him as “the inverse of the American Dream.” And if the image isn’t “perfect” according to the elements of Rickard’s demands, it’s a no-go. Everything in the image has to be composed, via the camera motion of Street View, to his very subjective, personal, and exacting standards.

Rickard’s exhibition at MoMA opened last September and closes on January 16, 2012. The show is aptly entitled “New Photography 2011,” and includes the work of five other photographers: Moyra Davey, George Georgiou, Deana Lawson, Viviane Sassen and Zhang Dali.

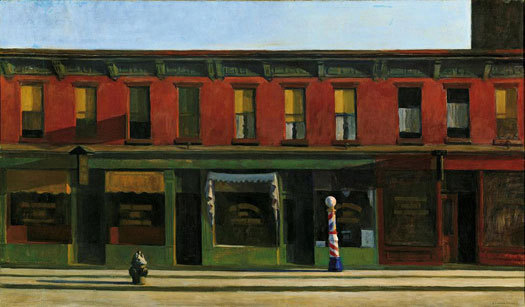

Doug Rickard is a modern-day photographer not unlike those who went before him. His imagery can be compared to the banal and mysterious cityscapes of painter Edward Hopper, or the great documentary photographers like Ben Shahn, Robert Frank and Walker Evans, all of whom shone a light on the shadows and made known the “invisible” — the disenfranchised and forgotten communities of America. Just as WPA photographers like Dorothea Lange combed America to document the great American Depression, so has Doug Rickard with his new camera: Google Street View.

Edward Hopper Early Sunday Morning. Oil on canvas, 1930. Collection of The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Purchased with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Photography by Stephen Sloman.

Ben Shahn Scene in Natchez, Mississippi. October 1935. Silver gelatin print.

Ben Shahn Scene in Natchez, Mississippi. October 1935. Silver gelatin print.

Walker Evans Group Outside Movie Theater, From Moving Automobile, Macon, Georgia. Silver gelatin print c. 1935.

Walker Evans Group Outside Movie Theater, From Moving Automobile, Macon, Georgia. Silver gelatin print c. 1935.

Ben Shahn Scene in Natchez, Mississippi. October 1935. Silver gelatin print.

Ben Shahn Scene in Natchez, Mississippi. October 1935. Silver gelatin print.

Walker Evans Group Outside Movie Theater, From Moving Automobile, Macon, Georgia. Silver gelatin print c. 1935.

Walker Evans Group Outside Movie Theater, From Moving Automobile, Macon, Georgia. Silver gelatin print c. 1935.

Walker Evans A Street Scene; New York, NY. 61st Street between 1st & 3rd Avenues. Silver gelatin print. 1938.