Loggers in Manistee, Michigan, circa 1885

Settled by Jesuits in the early 19th century, the town of Manistee, Michigan sits on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. Heavily wooded, it was a haven for loggers, salt miners and shingle merchants, and by the 1880s claimed to have more millionaires per capita than anywhere else in the nation.

Ezra Winter was not one of them.

Ezra Winter as a young art student, circa 1910

He was born there in early 1886, the son of Augustus Winter, a farmer who died of diptheria before his son was born. His mother remarried in 1907, and by then had recognized her son’s penchant for art: as family lore goes, young Ezra spent most of his childhood avoiding chores, preferring instead to draw pictures. After graduating from Traverse City High School in 1905 — a period during which he earned pocket money by drawing cartoons and designing postcards — he spent three years at Olivet College, and in 1910, made his way to Chicago, where he enrolled at the Art Institute. Here, he began his artistic studies in earnest, studying with, among others, the American portraitist Wellington J. Reynolds.

Chicago in 1911, as it might have looked when Ezra Winter was a student. © Collections of the Henry Ford Museum

At 24, Ezra must have found the lure of urban life utterly enchanting. There were parties to attend, clubs to join, and most of all, an endless stream of women to meet. Winter loved women, especially beautiful ones, and it wasn’t long before one of the models in his drawing class caught his eye: Vera Beaudette was a raven-haired beauty whose likeness was plastered over streetcars and signage throughout the city of Chicago, where she was the poster girl for the “Safety First” movement.

She was mysterious and alluring, and might have looked something like this:

(Please wait while the video loads.)

Even as a child, Vera was beautiful, with wavy locks of dark hair framing her angelic face.

An early photo of Vera and her mother, Ella. Photographer unknown

Photographs of Vera from this period are scarce, but as a young woman, she resembled the American actress Jennifer Connelly. She was comfortable in front of a camera (or indeed, an easel) and she was spirited and bubbly. She was beautiful, and she knew it.

Left, Vera shortly after she met Ezra Winter; center, a newspaper photo of Vera; right, portrait of Vera by Winter, circa 1910

Even as a young woman, Vera Beaudette was already showing evidence of extreme self-involvement. Over the course of the next half-century, her correspondence consistently revealed her own strong interior motives and no shortage of nitpicky selfishness. For her part, Vera was thrilled to have attached herself to someone as ambitious as Ezra Winter, and it is perhaps fair to say that both were blinded to the inadequacies of their union: Ezra was serious and sensitive, while Vera was hot-tempered and unpredictable.

Vera came from a long line of notoriously volatile women, not least of whom was her own mother, Ella: a socially ambitious dilettante who harbored fanciful aspirations of becoming an author, even going so far as to create her own trademark, printed in one of the few volumes that bear her name.

Ella Palma Beaudette in her "author's" photo; her trademark; and a formal portrait taken later in life

Ambitions notwithstanding, most published accounts of “E. Palma Beaudette” resulted not so much from talent as from what seems to have been a rather prickly personality. In the fall of 1912, she was arrested for selling advertising leaflets outside a Chicago church without permission, and a year later she finked on two cabbies who were driving crippled horses — an unsolicited gesture that wasn’t so much merciful as it was meddlesome, and led to the cabbies' inevitable arrest. Not long after that, Palma herself played the hapless victim when she was fired upon with a pistol by political rivals in a Chicago suburb. In her later testimony to police, she claimed to have been survived only because she fell, ‘‘hampered in her flight by her hobble skirt’’.

Comical postcards featuring the hobble skirt, circa 1910

Indeed, guns loomed large in Palma’s world. As early as 1902, she cited physical threats by Vera's father and soon obtained a divorce, granted on the basis of cruelty. (Interestingly, these were grounds Vera herself would cite in her own split from Winter some years later.) Palma’s version was a drama-infused yarn that included the following incendiary dialogue:

Question:

Do you remember the time he assaulted you at Kokoma (sic) Indiana?

Answer: He took and held me against the wall and held a revolver against my head and told me he was going to blow out my brains.

Question:

Do you remember in 1896 at your home, did he ever threaten you with a knife or a gun?

Answer:

Yes: he picked up a carving knife and threatened to cut my heart out.

Source: Ella P. Beaudette vs. Adolphus Beaudette, Cook County, Illinois Circuit Court Case; Gen No. 225, 865 Term No 11, 224; March 22, 1892

If there’s a lid for every pot, Ella Palma Beaudette Lovgren Neil defied the odds, and then some. She married two more times — briefly to a man named Lovgren, and then during one of the hottest Chicago summers on record, to a man called Albert Neil. By then, Vera was already pursuing romantic dreams of her own, which would take her far from Chicago, and away from her loving, if unstable mother.

Ezra Winter, The Arts: winning submission for the Rome Prize Competition, 1911

In May of 1911, Ezra Winter graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago. Thrree months later he was awarded a Prix de Rome. In August, Ezra and Vera married, and quickly booked their passage to Europe. They soon learmed that Academy laureates were not permitted to bring their wives, a fact that obliged Ezra to keep Vera — and their baby daughter Renata, who arrived in September of 1912 – secretly lodged in a rented room near the Academy.

A century ago, to win a Rome Prize meant a three-year year sojourn in the hills above Trastevere, with both a studio and a stipend, at the American Academy in Rome. Back then, the students — all of them male — were expected to study the classics:

The prize of Rome consists of a purse of $3,000 to be paid to each one of the winners, in painting, architecture and sculpture, in three installments during the three years of residence in Rome. Each beneficiary received, on his departure, his traveling expenses directly to Rome, and the same is true of his expenses to his home when the course is completed. The student must live in the academy building, which is beautifully located, during the first year. During the second year they travel presumably in Italy. The remaining year is spent in travel in countries where classic antiquities are found.

Source: "The American Prize of Rome," Fine Arts Journal, 1911

View of the North facade of the Villa Aurelia in 1911, as it might have looked when Winter arrived in Rome. © American Academy in Rome

But this was 1912, and even with the expectation that Academy fellows study the classics, it would have been an extraordinary time to be a young artist — even more so to be living in Europe. Consider, just for a moment, what's happening. In Paris, Georges Bracque is producing new experimental collages, Pablo Picasso is constructing guitars out of cardboard, and Marcel Duchamp causes a mild uproar when his Nude Descending a Staircase is rejected by the Salon des Independents. (A year later, it scandalizes American audiences at the New York Armory Show.) In Vienna, Egon Schiele makes explosive, if disturbingly seductive portraits, while in Italy, artists like Giacamo Balla and Umberto Boccioni turn to sculpture to explore the tactile nature of dynamic form in time. In May, Nijinsky debuts Afternoon of a Faun and less than a month later comes the premiere of Mahler’s 9th symphony: a lengthy, somewhat cerebral celebration of asynchronous sounds that seem to push against gravity — much the way the analytic cubists are attempting to do — by embracing multiple perspectives simultaneously.

Open another window and listen to this. And look at these paintings. Imagine for an instant that it is 1912. The Balkan War. The sinking of the Titanic. Kafka's Metamorphosis.

And this.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, detail, 1912

Giacamo Balla, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, 1912

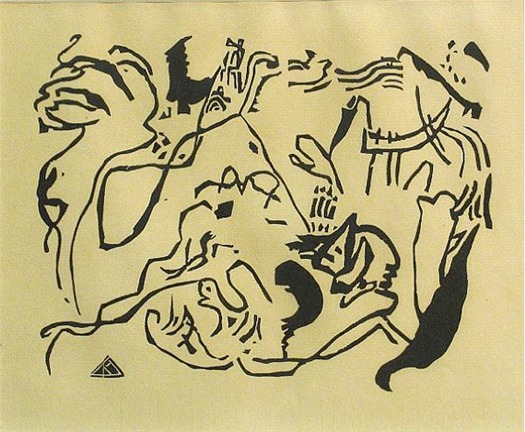

In Munich, Kandinski publishes the artist’s book “Klange” —a selection of prose poems that gesture to the relationship between sound and form — and that same year, writes “Concerning the Spiritual in Art” in which he argues for the soul of the artist.

Wassily Kandinsky, Jünster Tag, from Klänge, 1912

There is Dada and Cubism, and right there in Italy, a veritable Futurist explosion of new ideas. Of this astonishingly fertile period in art and music and dance, the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire would later write: “We must forget exterior reality and our knowledge of it in order to create the new dimensions.”

But Winter is awash in the exterior reality that is Rome, and feels no need to push boundaries as an artist. He is a pilgrim, on a search for something else, something that will rescue or redeem him. And so, rather than embrace the new dimensions, he tethers himself to a kind of big, baroque sensibility that is everywhere in his midst — in the churches and the architecture, the gardens and the city squares. He becomes, in a sense, transfixed by what was, not engaged in what will be. Ezra Winter is there, and he is not there. He is young, but he lives as if he bears the burdens of age. He looks not forward, but backward; not inward, but beyond.

And so, in these years just before the outbreak of World War I, the artist embraces the new world by immersing himself in an ancient one. It would later prove to be fruitful educational sojourn for the young painter — a period during which, according to The New York Times, he “roamed the continent of Europe, pushed on into Greece, then into Turkey and the near east.” He tours palaces and ancient cities, examines architectural and archaeological oddities, and becomes fascinated with the relationship between the art of painting and the act of building.

For Winter, the age of wanderlust has begun, and he becomes tireless in his pursuit of a kind of majestic, awe-inspiring art — an art that is arguably at odds with the sorts of things that are going on in studios all over Europe. It was likely during this time that his fundamental propensity for scale and drama took root, making his later foray into mural painting an almost foregone conclusion. Eagerly — if unwittingly — Ezra Winter was cementing his position as a dyed-in-the-wool classicist, even as he was living in a world that was becoming, in fits and starts, more modern by the minute.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

Film footage courtesy of the Travel Film Archive. Music: Be My Little Baby Bumble Bee © 1912. Music by Henry I. Marshall. Lyrics by Stanley Murphy. Vocals: Milly Murray and Ada Jones.