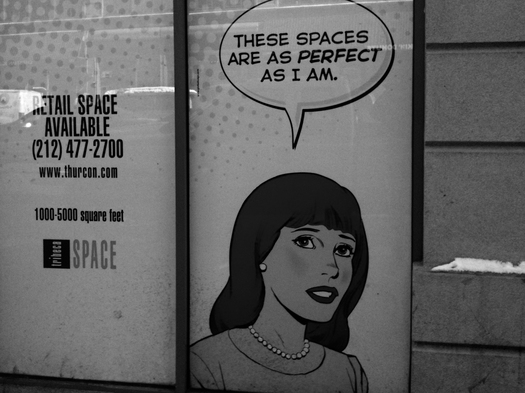

New York, NY, 2010. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.

Certain elements of the built environment are designed to demand everyone’s attention: They fairly scream at your eyes. Others, merely mumbling, are easily missed. In 2009, Matthew Frye Jacobson was deep into the research on his latest project when he had a pivotal conversation that drew his attention to one of those quiet features of the cityscape that reveals something important, and possibly urgent.

Jacobson is the chair of American Studies at Yale University, and the author of (among other books) Roots Too: White Ethnic Revival in Post-Civil Rights America and Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. His current project, now called “Historian’s Eye,” traces back to the inauguration of Barack Obama — occurring in the shadow of national, even global, economic calamity. This felt like a “double-edged” moment of hope and despair, Jacobson recalls, and that feeling has persisted: “Virtually everyone I talk to feels some version of that.”

In capturing this still-ongoing moment, Historian’s Eye has departed from Jacobson’s prior work in several ways. Most obviously, it has taken the form of a Web site, rather than a book. Instead of a decisive set of conclusions in written words, it collects Jacobson’s photography (a practice he took up only a couple of years ago) and audio recordings of interviews – more a gathering of material to be interpreted. And unlike a static bound volume, it’s digitally dynamic, open to contributions from others. The form it has taken, in fact, has been shaped in real time — by epiphany-inspiring conversations like the one Jacobson had with Bonnie Fox.

Jacobson interviewd Fox, an unemployed woman in her 60s, living in Manhattan, in 2009. She described job-hunting alone at her computer, and receiving her unemployment benefits electronically. And she mentioned something Jacobson had been wrestling with: There wasn’t much of a public dimension to the economic crisis.

The only visible evidence she could point to, really, were the signs around her Upper East Side neigborhood, indicating commercial vacancies.

Chehalis, WA, 2010. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.

That insight, in effect, set Jacobson off on the curious-sounding mission of documenting this easily overlooked visual trace. And so he’s ended up collecting nearly a thousand photographs of “Space Available” signage, from dozens of cities all across the country, in a dedicated section of historianseye.org. (Other sections of the site are devoted to “Obama,” “Places,” “Immigration,” “Protest,” and so on.)

I learned about all this by way of a recent Jacobson lecture about the project at Princeton, and for me it was the collection of “Space Available” images that stood out. Suddenly this near-invisible, mundane element of urban environments everywhere popped into focus. When grouped in a relentless series of hundresd of images, the signs struck me as adding up to a kind of involuntary monument to the Great Recession.

As Jacobson explains in our converstion below, my reaction is pretty much what he’s going for: The goal of the Historian’s Eye is “to get people to notice in a different way,” as he puts it. “I want to see whether I can get people to slow down and look at and think about this historical moment.”

Trenton, NJ, 2010. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.

The “Space Available” collection is more than 900 photographs of, basically, buildings with signs indicating vacant commercial or retail space. Let’s face it, that sounds incredibly boring. Why should we look at pictures of these mundane signs?

While there are a couple of images in it that I’m attached to, for the most part that gallery is not functioning in a way that’s meant to arrest you one image at a time. It’s the scale. There’s something cumulative about it.

I go back to the Bonnie Fox interview, where she said there’s nothing public about this crisis. And those signs were one of the few public markers she’d picked up on. Once you start noticing them, you see them everywhere you go — these massive numbers of fairly recently closed businesses. And it just goes unremarked and unnoted. Everything in the culture is privatized, including the crisis itself, right? One of the aspirations of that part of the site is to make that public again, to make it part of the public conversation about what’s happening to our society.

It’s a very hard crisis to photograph, for exactly the reasons she was talking about. I’d been out in the world trying to photograph it, and I couldn’t find it anywhere, until she tipped me to the space available signs. “Space Available” became a subgenre of its own, in my mind.

San Diego, CA, 2010. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.

You have other sections on the site devoted to specific places and specific cities, and these sign images pop up there. But when you group them, the collection seems to form its own geography, to me anyway.

And it raises a question: What are we going to do with all this? These are our towns and cities that we’re talking about, and there are these kind of empty husks everywhere. What’s going to happen to this space, will this space ever be filled again, what can these spaces be used for?

B inghampton, NY, 2010. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.

You’ve suggested it expresses a kind of new “normality.” What do you mean?

There are certain places where it’s astonishing and it gets your attention. Like Main Street in Binghamton, New York: It’s two miles long and every single block is largely vacant. It’s stunning.

But that’s rare. What’s more often the case is that it’s one store here, two stores there, in a way that’s really under the radar, so it is very quiet and easy to not notice so much. So it does become just a “normal” part of the landscape: “Of course there’s a vacant storefront on this block.”

Things weren’t always that way. So that sense of “normal” is something I’m trying to rouse people out of.

Cleveland, OH, 2011. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.

Since that 2009 interview with Fox , we’ve seen the Occupy movement spring up. And you now have a section of pictures from those events too. It’s not the same as bread lines, but has it changed your view about the absence of a public manifestation of the crisis?

In a way it has. The Occupy movement, whatever else it turns into, one thing it has already achieved is that it has shifted the national conversation in a really interesting and important way. It’s normal now to open a newspaper and find an article about income inequality. It’s stunning to me how quickly that happened. I’d need more distance on it, and to see what happens next, but it does feel like a different chapter, like there’s less complacency.

San Antonio, TX, 2010. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.

Speaking about the project at Princeton, you mentioned hoping the pictures would lead “to reflection that can be politically useful or usable.” Maybe you could expand on that.

That was in response a question from the audience, from an older, seemingly kind of 60s activist who was pressing me on the politics of this, and was himself impatient with what I was implying. What he wants is for someone like me to urge something more immediate and more revolutionary. I was saying that reflection can be revolutionary — it’s just not going to be speedy.

As a historian, I take a longer view of the past, and of the future. One can look forward from this point with a different idea of what’s possible, based on what’s in the archive. But also later on, people can look back at the archive, and see something deep about what was going in the United States in this handful of years.

That’s in line with other work I’ve done as a historian. There’s nothing impatient or fast about it. On the contrary, it’s meant to be reflective and patient. There’s a great phrase I heard from one of the activists involved in early 1960s Civil Rights activism, saying what that took was “revolutionary patience.” That idea of patience itself being revolutionary I think is really profound. It’s something that our culture doesn’t necessarily encourage.

One of the things that’s philosophically interesting to me about the project – some of these photographs I think are beautiful. There’s a kind of sobering beauty to so much of what I’ve seen. And that’s part of the story too. There’s a lot of pain and a lot of distress, but a lot of beauty, too, in a way.

New York, NY, 2010. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.

Sometimes the sign is blight on the beauty — and sometimes the viewer has the absurd moment of appreciating a “space available” sign.

As you can imagine, some of my friends have made a lot of fun of me (laughs) – because of the amount of time I’ve spent running around the world chasing “space availabe” and “for lease” signs. But I think I was proven right – even the people who needled me the most have to admit that it’s adding up to something that was worth doing.

Historian’s Eye is a collaborative online project, and Jacobson is actively seeking (and receiving) contributions from a range of other photographers, researchers, and others with images and interviews that tie into his themes. The site is also functioning as a tool for educators. You are encouraged to see what others have contributed, and to get involved yourself, here.

Reading, PA, 2010. Photo by Matthew Frye Jacobson, from "Space Available," on HistoriansEye.org.