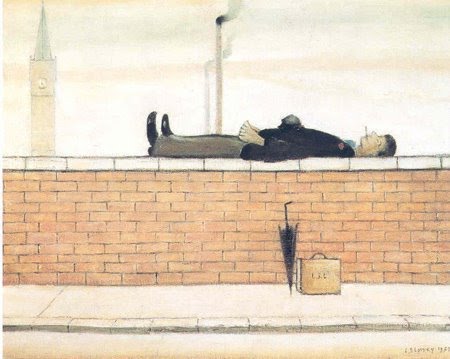

Man Lying on a Wall, by L.S. Lowry.

After my post here the other day on “dancing about architecture,” a friend with a vocabulary superior to my own dropped a line to say it “made me think about the practice of ekphrasis.” Specifically, it made him think about this site, which addresses “L.S. Lowry's painting Man Lying on a Wall and Michael Longley's ekphrastic response by the same name.”

Maybe it’s a gaffe on my part to signal my sketchy education by revealing that this concept was news to me. It was happy news, actually — and not just because the word “ekphrastic” is so obviously fantastic. In addition to literal instances of dancing about architecture — which seem to me to count as being in the realm of ekphrasis — what I was trying to get at the other day was my enthusiasm for creative responses to creativity, in general. Possibly ekphrasis is the concept I was grasping for without knowing it.

In the specific instance my friend pointed out, what we have is a painting that inspired a poem — forming an “ekphrastic pair.” Maybe that seems a long way from, say, what a typical music critic, or a typical anything critic, does. (What music critics do is of course the matter that inspired the phrase “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” The underlying assumption is that the critical response is fundamentally subservient to the thing critiqued.) To this objection I would say: Maybe. It’s all in the execution, isn’t it? Consider Carl Wilson’s book Let’s Talk About Love, technically a response to Céline Dion’s album Let’s Talk About Love. If there’s a mismatch in that ekphrastic pair, I’d say the “critic” created something more intellectually compelling than the “artist” did.

On the flipside, one could object that Longley characterizes his poem as an “homage” to Lowry’s painting, and this is distinct from criticism (of music or anything else). Again I say: Maybe. In this case I think it depends on definitions – what you think the job of criticism should be, as well as what counts as art (or even creativity).

Speaking of definitions, I should acknowledge that the Merriam-Webster online dictionary defines ekphrasis as “a literary description of or commentary on a visual work of art.” What I want to do is make “dancing about architecture” into a broader version of that idea — wherein the “commentary” need not be “literary,” and the “work of art” doesn’t have to be a painting or sculpture, or even “visual.” (My friend simply called it "art about art.")

So to riff in that direction, consider Apple. Way back in June 2010, I wrote a column about the relationship between Apple’s lauded products, somewhat mysterious supply chain, and the consumer. In February 2011, Joel Johnson wrote a (much better) cover story for Wired exploring that relationship. And most recently, Mike Daisey has addressed the same thing in a monologue, “The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs,” which has of course been a considerable success, with more impact that Johnson's great article and certainly way more than my column. Certainly This American Life has never been tempted to devote an entire show to anything I’ve written.

Daisey's show doesn’t fit the dictionary definition of ekphrasis, but could a live theater piece — in which a devotee of Apple product design radically rethinks his views after investigating the company's manufacturing practices — be an example of “criticism”? I would say yes, and evidently a pretty effective one. It’s also, obviously, an original creative work. So let's concede that it's ekphrasis-y, at least.

And I think that’s not unrelated to its effectiveness. Performing a monologue about a consumer-products company, in other words, is like dancing about architecture — in this case, very, very well.

Promoted as: "A hilarious and harrowing tale of pride, beauty, lust, and industrial design."