Barry Faulkner, left, and Ezra Winter, center, photographed in their Grand Central Studio during a lunch break, while working on the Eastman School of Music murals, about 1924

The 1920s was a period of enormous activity for Ezra Winter, who with his growing staff, produced murals for the New York Cotton Exchange, The United States Chamber of Commerce and the Strauss Building in Chicago. At a frantic clip, Winter presided over a team of carpenters and assistants who performed duties large and small — from inking outlines to stretching canvasses to mixing pigments and ordering supplies. There were meetings to attend, invoices to prepare, complex, often alchemical decisions about paint and mortar, and strategic choices about how and when to intercede in business decisions with an assortment of bureaucrats, architects and humorless municipal authorities. (In such matters, Winter tended to be aggressive and — with regard to financial details — unequivocally blunt, often to the point of rudeness.) In their starched white long-sleeved smocks, his team sooner resembled a medical unit than a group of artists. Tensions high, deadlines looming, the atelier performed its own kind of triage, with Ezra Winter front and center for every single decision.

Enter prohibition.

Beginning in 1920, the constraints set forth by the Eighteenth Amendment and the ensuing Volstead Act made drinking an illegal activity. For Winter, this must have come as something of a shock. Gone were the long, wine-enhanced lunches he would have enjoyed while touring the Italian coast, the discussions at the Academy bar over lazy aperitivi in the late afternoons. No longer free to travel and dream, he was harried and overworked, craving release. And here, the very studio that framed his livelihood turned out to be the perfect place for parties, particularly big ones, with music and costumes and booze. If he couldn't travel to distant lands, he could at least bring the eclecticism of his wide-ranging group of friends to entertain themselves in his spacious atelier.

Group photo from a party in Winter's Grand Central Studio, sometime in the late 1920s. Winter is pictured at far left. The young woman in center (seated, front row) may — or may not — be Frida Kahlo

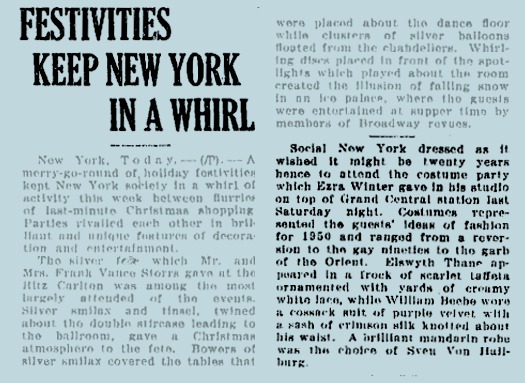

At once centrally located and clandestine in its lofty perch, Winter's studio provided the perfect party locale, and his social roster drew from a long list of celebrities and civilians alike. There were writers and actors, socialites and debutantes as well as a cast of unlikely suspects (Rube Goldberg! Moss Hart!) added to the mix. Winter frequently introduced themes, too, inviting his guests to come in costume. Come as your favorite deep-sea creature, read one invitation. Dress as you imagine they will in the future — say, in 1950! — advised another. The society pages were full of reports of who attended and what they wore, and it wasn't only New Yorkers who cared about such events: there was coverage as far as Texas and Georgia.

A story about one of Winter's parties in a New York newspaper, early 1930s

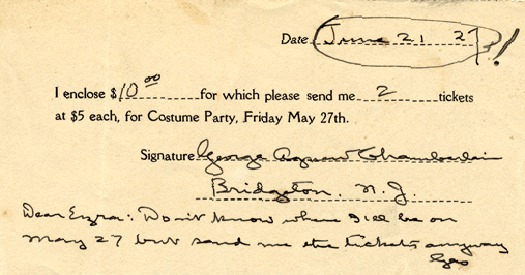

To help defray costs, Winter issued tickets.

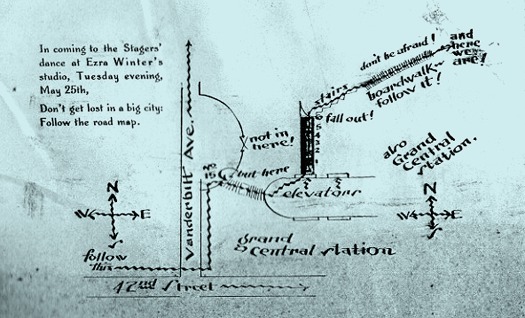

And drew maps:

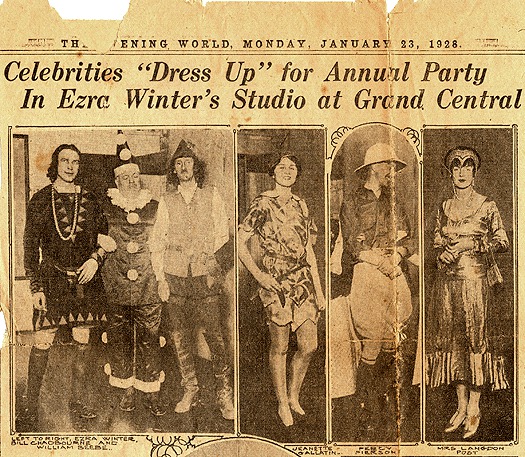

With his pals Bill (William Chadbourne, a lawyer) and Will (the zoologist William Beebe) Winter soon transformed his studio into a haven for giddy frolic. The parties became a palpable means of escape for the serious painter — a place to dance and dress up, to flirt and cavort and forget, for a few hours, about all the pressing obligations that otherwise circumscribed his days. These soirées proved a kind of temporary escape, a respite from ordinary life to the extraordinary world of make-believe.

Left, the hosts: Winter, Chadbourne and Beebe. Featured at far right is Mrs. Langdon Post whose husband was an advisor to Franklin Roosevelt when he was Governor of New York

Left, the hosts: Winter, Chadbourne and Beebe. Featured at far right is Mrs. Langdon Post whose husband was an advisor to Franklin Roosevelt when he was Governor of New YorkIf Chadbourne provided some kind of logistical support for these events, it was Beebe who added a true element of romantic mystery. Educated at Columbia where he was declared something of a boy genius, William Beebe graduated just before the turn of the century and took a job at the Bronx Zoo. His first marriage, to the beautiful Mary Blair Rice, ended in divorce in 1913 — curiously, on the grounds of cruelty, just like Ezra’s marriage to Vera.

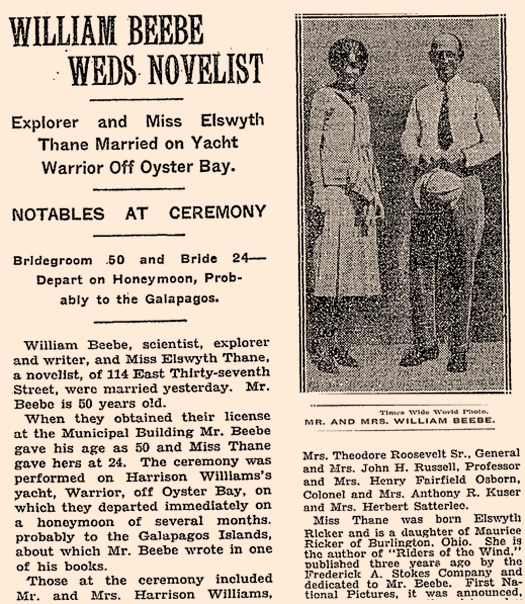

Fourteen years later, Beebe married the novelist Elswyth Thane, who was half his age. Ezra was at the wedding, which took place on a yacht, and included many cultural and social luminaries — not least of whom was Eleanor Roosevelt.

The Beebe Thane marriage arrouncement in The New York Times, 1927

Yet within a few years, the Beebe-Thane union had become a marriage of convenience, with Thane traveling to Europe for research while Beebe continued his frequent visits to more lush, tropical places, including Haiti, the Galapagos Islands and the Sargasso Sea. By the early 1930s, Beebe had fallen in love with a young ethologist, Jocelyn Crane, who worked with him on Nonsuch Island in Bermuda.

Jocelyn Crane in an undated photo. She later married Donald R. Griffin, a distinguished professor of animal behavior at The Rockefeller University in New York. Thane died in 1998.

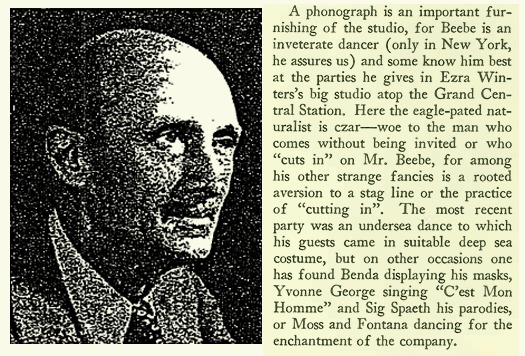

Beebe's voyages were numerous and well-reported in the national press: he was something of a celebrity, tall and striking, intrepid and adventurous and exceptionally prolific. He also loved to dance.

Left, portrait of Beebe from a 1949 profile in The New York Times; right, excerpt from a Talk of the Town piece in The New Yorker, early 1930s

And then, on Wednesday August 15, 1934, Beebe made history by descending more than 3,000 feet below the ocean’s surface in a bathysphere.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

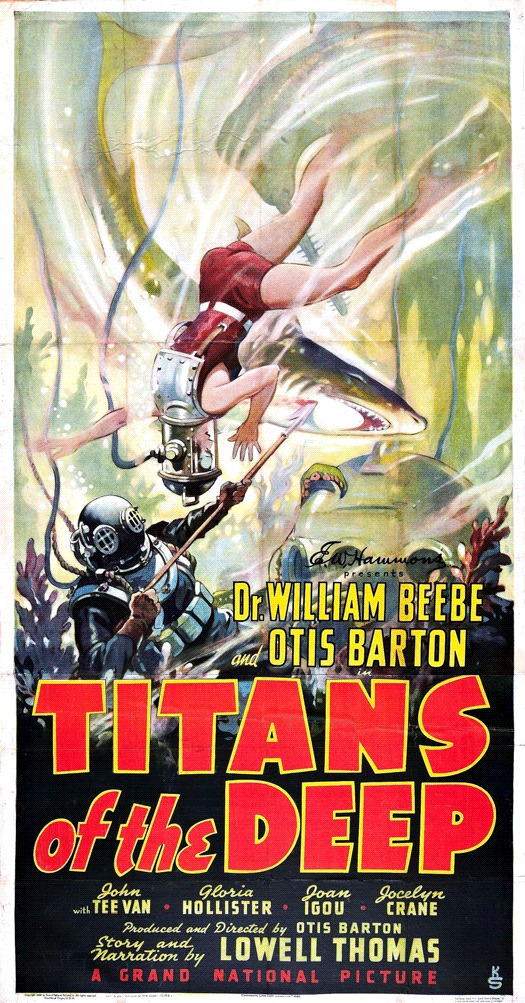

Music : Bill Callahan, Bathysphere, recorded live in Dublin, 2011He was accompanied by fellow explorer Otis Barton, who later produced and directed a fictional account of their historic dive in the film “Titans of the Deep”. Crane was listed as a cast member.

The film's description made Beebe sound more like a matinee idol than a zoologist. "Brave and beautiful girl scientists facing death in the ocean's depths... battling fierce sea demons... men and monsters in deadly combat... the dangers met and conquered by science!"

Beebe — ornithologist, naturalist and all-around polymath — lived, when not visiting exotic ports of call, surrounded by his significant piles of books in the Hotel des Artistes. (On top of his other many extraordinary talents, Beebe had an encyclopedic knowledge of Kipling and Shakespeare.) Above all, he was an adventurer, and hard-working though he was, Ezra Winter craved adventure: no longer tethered to his family, he was virtually free to accompany Beebe on a number of trips — including at least one to Bermuda where the focus seemed to be tennis, supported by a diet rather heavily weighted toward the consumption of alcohol.

Beebe and Winter’s mutual friend, the publisher George Palmer Putnam, was equally smitten by the romance of exotic sea travel, and in the Spring of 1926 organized an 8,500 mile expedition to Greenland, in quest of specimens for the then-new Hall of Ocean Life in the American Museum of Natural History. Though Beebe was not in attendance, the ship’s roster included an eclectic mix of specialists, including an ichthyologist, a taxidermist, a motion picture photographer, and Putnam’s 12-year old son David. (Five years later, young David would —under the tutelage of his stepmother's trainer — learn to pilot a stunt plane. But then, not everyone has Amelia Earhart for a stepmother.)

Also on board was Ezra Winter.

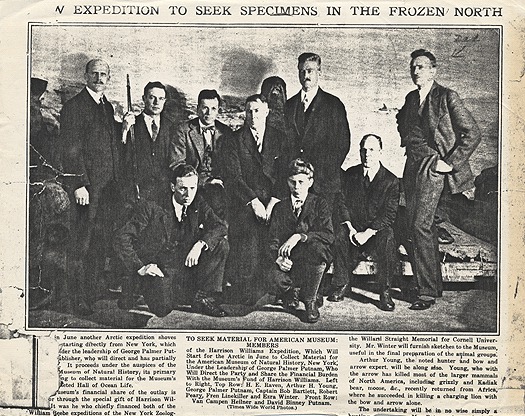

A formal portrait of the members of the arctic expedition was published in The New York Times in May, 1926, with Winter standing at far right.

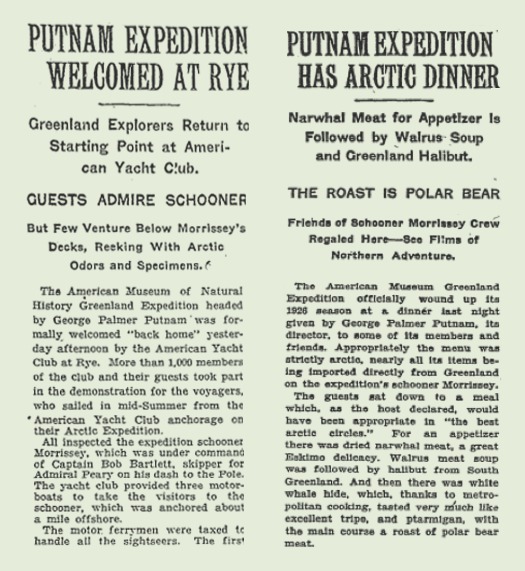

The Putnam expedition was widely reported in the press, and an open competition was held so that ordinary people would have the oppportunity to participate: nearly 10,000 people applied. Even after the trip had concluded, there were reunions of the crew, including one in which they dined on narwhal meat, walrus soup and roast polar bear.

Excerpts from two stories that ran in The New York Times in the spring and fall of 1926, respectively

For his part, William Beebe was probably delighted to be excluded from the Greenland trip. In an interview given in the late 1940s, he admitted that he'd been greatly relieved to return to the tropics following his historic 1934 descent in the bathysphere — a trip, by the way, that he never repeated, claiming that deep sea diving held no inherent scientific value. (And then there was the cold. "Oh my," admitted Beebe, post-bathysphere. "It's terribly cold under water, and I hate the cold.") Curiously, the most enduring element of that expedition was his discovery of the pronounced color changes which occur below sea-level — an observation he would have eagerly shared with his friend Ezra Winter. Paradoxically, while the muralist may have envied the certainty of science and the romance of adventure, Beebe himself thrilled to nothing more than the visual splendor spied through a glass bubble, far below the crashing waves.