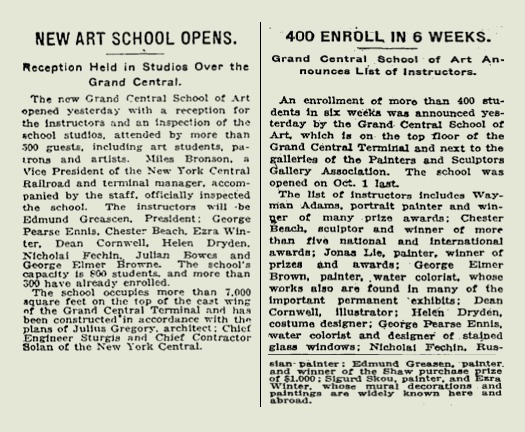

The New York City-area press reported on the new art school which received a record number of applicants in its early weeks

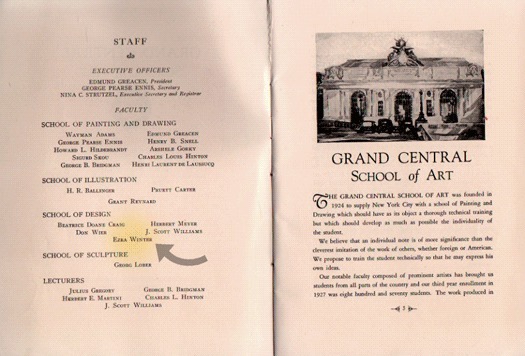

In 1924, under the combined direction of John Singer Sargent and Daniel Chester French, a group of New York-based artists decided to open an art school in Grand Central Station. The attic of the east wing contained a 7,000-square-foot offered an ideal location for teaching painting and sculpture, costume design and commercial illustration. For design faculty member Ezra Winter, whose own studio was located only steps away, the school provided a perfect opportunity to start teaching.

It also turned out to be an excellent way to meet women.

Winter spent a great deal of time thinking about women. He thought about Vera, who he sometimes longed for, if only to have someone to talk to who had known him for so long. He thought about his mother, who loved him but always seemed to need something from him — attention, reassurance, and most of all: money. And he thought about his three daughters, living with their mother in Chicago, and who were growing up so quickly.

In a letter to them in April of 1924, Winter writes:

I think very very often of you all and wonder how you are getting along, how you are taking care of yourselves, what you eat, if you change your underwear often enough—before it smells, if you brush your teeth and hair, if you keep your things in order, in fact, if you are training yourselves to be wholesome, clean, helpful companions to whoever you meet.

To Vera, he writes:

I’d like to be with you to hold your hand but that would not be proper.

By the winter of 1925, the divorce settlement confirms Vera as the childrens’ sole guardian, their home to be deeded to her for life. She would receive $300 per month in alimony, with Ezra paying half her legal fees and all her household expenses, in addition to the childrens’ educational and medical needs.

But sandwiched in between such serious matters are notices of a different sort: invitations and letters, programs and playbills — material evidence of a series of social forays into the roaring Manhattan of the 1920s undertaken with reckless abandon — and in the company of an extraordinary array of young actresses, elegant dancers and captivating socialites. In the spring of 1925, someone called “Dixie” writes from Palm Beach, while “Peggy” sends postcards from Santa Fe. He spends time with Martha Bacon, who invites him to a rodeo at Madison Square Garden. Alice DeMar, heiress to a massive fortune (at the age of 18, she inherited nearly 10 million dollars) writes to him too, as does Rosamund Pinchot — who would later be dubbed “The Loveliest Woman in America” by The New York Times. She accompanied the painter to an afternoon performance of the Isadora Duncan dancers.

The American actress Rosamond Pinchot in an undated photograph. A niece of Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot and a cousin of Edie Sedgwick, Pinchot took her own life in 1938.

There were artists in Winter’s midst too, with whom he who may or may not have been on more intimate terms: Alison Mason Kingsbury, a painter who assisted him for several years in the late 20s; Anna Colman Ladd, the sculptor; and Isabel Cooper, a young naturalist who painted reptiles and amphibians.

And then, in March of 1926, Ezra Winter turns 40. His thoughts turn to even more beautiful conquests, and even younger women.

Enter Jean Tolmie: Miss Toronto of 1926.

Jean Tolmie in her winning banner as Miss Toronto, 1926

It is not clear what led Winter to meet the lithe Canadian beauty, but it is possible — likely, even — that beyond his orbit of famous artists, there was a secondary bubble of people famous simply for being famous. And of these, there were no doubt many whose appeal lay simply in their beauty. And Ezra, fraught with bills and deadlines and incessant obligations, was all to eager to surround himself with anything that was beautiful.

And so it was that he came to be a judge in the 1927 Miss America Pageant.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

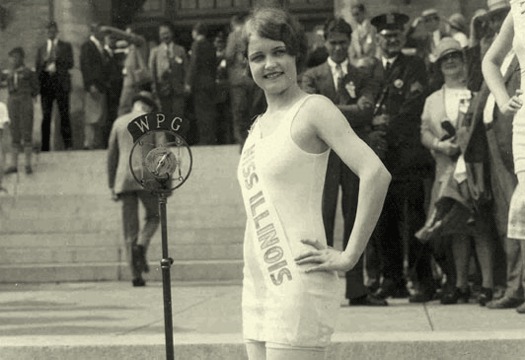

Footage made available courtesy of Emil Salvini, Tales of the Jersey Shore. Music: Miss America, Capital Ghost.On September 9, 1927, Winter and his fellow judges crowned 16-year old Lois Delander as their Queen. An honors student in Latin back in her home town of Joliet, Illinois, Delander won on her parents 20th wedding anniversary.

Lois Delander and her parents, after her 1927 win

Delander would have been only a year older than Winter's eldest daughter, Renata.

Lois Delander photographed after the swimsuit competition. Ezra Winter and his fellow judges stood behind her at the top of the stairs

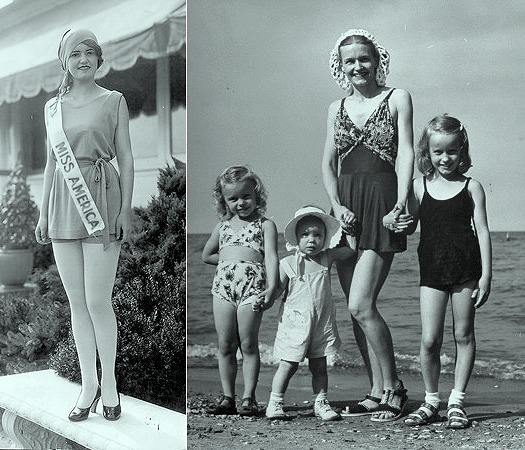

After the pageant, Delander went back to complete high school. She later married and raised three daughters. She died in Chicago in 1985.

Left, Delander as Queen; right, with her three children

As the gulf widens between the aspirational and the real — between the projected self and the authentic self — Winter immerses himself in all that is beautiful and lyrical and dream-like. A three-week trip to Bermuda with William Beebe in the summer of 1928 is spent mostly dining and dancing, but within a matter of weeks he is back in New York, drafting plans for the Rochester Savings Bank, Cornell University’s Willard Straight Hall, and the Public Library in Birmingham, Alabama. The late 1920s finds Winter hard at work at murals for the United States Chamber of Commerce in Washington, DC and a number of banks in Rochester, New York. He is exhausted and under stress, chain-smoking through it all. (There was some speculation that this attributed to the grayness of his palette during this period.)

Sometime during the summer of 1929, Winter meets and becomes obsessed with a beautiful young dancer who is everything Winter isn't: their brief, tempestuous courtship will take place just as the country is heading into an extraordinary and unprecedented collapse. Buffered by beauty and obsessed with youth, Ezra Winter soldiers on.