From an article in The Waterbury Republican, January 26, 1941

Chapter 11: Impedimenta

By 1934, Ezra Winter is hard at work on the murals for the United States Supreme Court. Financed by the Federal Government at a cost of six million dollars and developed in conjunction with five middle Western states — Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Missouri — Winter’s principal contribution is the intricate color scheme and lighting pattern in the Grand Hall, the main Courtroom, the Library Reading Room and two conference rooms.

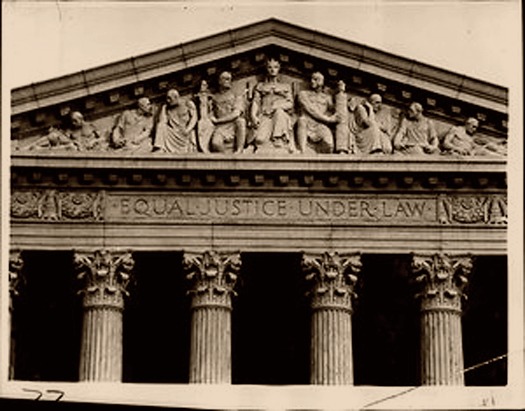

Press photo of the United States Supreme Court, circa 1934

Coffered ceiling of the United States Supreme court in a recent photograph

Within the same year, he will complete seven 28-foot murals for the General Clark Memorial in Vincennes, Indiana. To do the proper research, he rents costumes and hires models to pose in them, re-enacting the Louisiana Purchase, the Battle of Fort Sackville, and the surrender of the British.

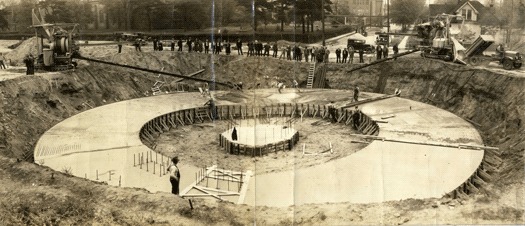

Digging the foundation for the General Clark Memorial, early 1930s

Winter's murals in a recent photograph

By 1936, he will embark on the murals for the Federal Reserve Building in Washington, DC. That same year, he is elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, receiving their Gold Medal a year later.

Gold Medal of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, designed by Adolph Alexander Weinman

And soon after this, Winter is one of several artists commissioned to produce a mural for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, to appear outside the Court of States where he has been asked to depict America’s leading industries: mining, lumbering, ranching, cotton, tobacco, grain, manufacturing, shipping, aviation and land transportation. Coming out of a decade of economic depression, and celebrating “The World of Tomorrow,” the fair’s exhibits showcase futuristic notions about America’s aspirations for industrial progress.

Overwhelmed by commissions, Winter works constantly— but it is not clear now productively.

Murals, in such a public and social arena, have a central and highly visible role. Yet unlike the more arguably spirited and modern work produced by artists like Stuart Davis, Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston and others (there were nearly 100 murals at the fair, including Fernand Leger’s very first American commission) Winter’s contribution — fronted by a lone poplar tree — is staid and lifeless, more commemorative than innovative. Though visibly more streamlined than many of his more Beaux-Arts inspired paintings, the mural appears oddly inert against the tide of tourists passing through.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

Music : 1939 Recording of Billie Holiday singing Strange Fruit, adapted from a poem by the American poet Abel Meeropol

And then, later in 1939, Ezra Winter is invited by the American poet Archibald MacLeish (then newly appointed as Librarian of Congress) to decorate the Library’s new annex — The Jefferson Reading Room — with four murals inspired by Thomas Jefferson's thoughts on freedom, labor, education, and democratic government.

Just as the Radio City mural beckoned as an opportunity for autobiography, so, too, do the Library of Congress murals speak to Winter on a deeply personal level. Jefferson’s notion of the sovereignty of the living generation — simply put, the idea that life belongs to the living — would have been a striking concept for the muralist, whose admiration for historical precedent was perhaps matched only by a deferential sense of ancestral duty.

For someone who lived so indelibly in the past, what would this have meant? One imagines long conversations between the poet and the painter: indeed, theirs was a friendship that endured far beyond the work that initially united them. But where MacLeish sat back and contemplated philosophical notions about the world and those of us in it, Winter, always the worrier, sequestered himself within the most menial of details. Perhaps they balanced one another — MacLeish, the patrician, Ivy-League educated scholar, and Winter, the self-taught, self-doubting farmer's son.

Thirty years later, on the occasion of the first lunar landing, MacLeish would write about unfathomable emptiness. He might have been writing about Ezra Winter.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

Archibald MacLeish reciting his poem, Voyage to the Moon, 1969

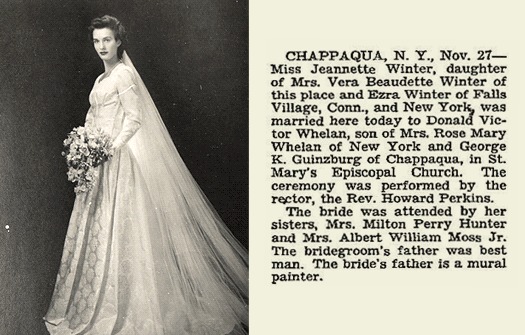

It would take the artist two years to complete the Jefferson paintings, years during which he would struggle with his finances, with his deadlines, with his very sense of purpose. Winter’s correspondence during this period hints increasingly at the fissures that will begin to widen over the next decade, even though it is a period equally marked by personal success. Following an earlier marriage (and a brief stint as a Chesterfield Girl) Renata Winter marries Milton Hunter at Juniper Hill on July 6, 1938. A year later, her sister Jeanette graduates from high school and begins modeling for Kodak and for Vogue: in late autumn of 1942, she will marry Donald Whelan. In between these happy events, Saranne, the third daughter, elopes and marries Albert Moss, Jr.

Renata Winter and her children with Milton Hunter and their wedding party, on the grounds at Juniper Hill, July,1938. Ezra and Pat Winter are pictured in the second row, far right

Jeannette Winter's wedding photo and announcement in The New York Times, November 27, 1942

Jeannette Winter's wedding photo and announcement in The New York Times, November 27, 1942

Saranne Winter, known to as "San", in an undated photo

Throught these active years, Winter is profoundly in debt, writing to his daughters and attempting to explain his situation. The Canaan property, he confesses, is “mortgaged to the limit”. His earnings during the previous six years are “one third what they used to be”. In letters to creditors and clients, the artist routinely seems to be asking for more money and more time. One wonders: did he accept multiple commissions for monetary reasons alone? Could his struggle have been merely a financial one, or did it reflect physical changes, even cognitive shifts? Was Winter’s long-held view of the intrinsic role between architecture and decoration no longer achievable, sustainable, even valid?

To MacLeish he writes:

I have had several private little revolutions with my designs or myself, and have begun all over again many times. I believe you will understand this.

To Vera he writes:

I have not been well since I finished the last job and find it very hard to think or work ... In this situation you must try to be helpful also and take some responsibility. I am not immortal and like other human beings I some times need help.

Tethered, as ever, to family obligations — Vera’s alimony payments, his mother’s ailing farm — Winter's responsibilities endure while his support structure dwindles. Was it harder to find staff in the rural Berkshires, more difficult to obtain supplies during the Depression? Did the man who once held spectacular soirées in his Grand Central atelier find himself lost in country life, removed from the pulse of urban connectivity, doomed to a life of self-imposed exile? Was Pat's business — which thrived on the very land that virtually cemented that exile — a source of foretold imprisonment?

An article in The Waterbury Republican describes the Connecticut studio, citing in particular the impedimenta that hold his canvasses in place. It is a stunning concept: at once an armature and a support for his work, it is, at the same time, a palpable impediment, a barrier to its very fulfillment. The studio — once a place of spectacular creative and financial opportunity — has become a site of conceptual and indeed, spiritual dislocation. Ezra Winter is beginning to slow down.