James Bridle’s Dronestagram has been greeted with a remarkable flurry of attention, particularly considering that so far it consists of just nine images. Probably this is because it’s a compelling concept — and indeed most of the coverage has consisted of summarizing the concept. So here it is: Bridle tracks reports of drone strikes; does his best to determine where they occurred; grabs a satellite image of the area from Google Maps; and posts that image on Instagram and Tumblr, with a short summary of whatever information about the strike is available. The idea, Bridle writes, is “making these locations just a little bit more visible, a little closer. A little more real.”

Via Dronestagram

Since Google Maps offer a muddier and less appealing visual experience than most of what’s on Dronestagram so far, I was curious if Bridle was using Instagram’s famous filters on the images he posts. (Nothing I read addresssed that question.) I asked, and he does, although not in any systematic way. “I usually pick whichever one enhances the selected image best,” he explained via email, “gives it some contrast/depth.”

At first this sounds fishy. How do the corny aesthetic gimmicks of the photo-sharing network (gimmicks that of course I use routinely to tart up my own distinctly unimpressive Instagram pictures) work in the service of making these locations “more real”? But upon reflection, I think the decision not only makes sense but is necessary: Part of what’s interesting about Dronestagram is that it’s interrupting a platform associated with prettified images of breakfast, pets, sunsets, old signs, babies, and parties to bring the latest news of drone-inflicted fatalities. So using the platform’s visual vernacular makes the images stand out by almost blending in — just one more quotidian snapshot, except not at all.

Via Dronestagram

Via Dronestagram

Using filters also indirectly acknowledges the gap between these images and the real places they represent: Actual public information about precise drone-strike locations tends to be sketchy, and Bridle relies on The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and press accounts. So the images on Dronestagram aren’t so much documents as signifiers. And this limitation is of course a reflection of one of the most troubling aspects of drone warfare: its determinedly murky nature.

As I was putting this post together, I happened upon this Salon story about another drone-tracking effort: Dronestream. Josh Begley (evidently as part of a Douglas Rushkoff class at NYU) has set out to tweet basic data about every reported U.S. drone strike since 2002. His first twelve hours of tweeting brought him up through March 2010. If Bridle is trying to infiltrate your informationflow, what Begley is really offering is the overwhelming litany as a form of polemic — a strategy that reminds me of “Break The Record,” by Anne-James Chaton and Andy Moor, a music piece consisting largely of statistics regarding the scope and cost of security at the Olympics, and “All You Need Is A (Separation Barrier),” a short and highly effective radio piece by Niall Farrell in the form of an audio list of walls and structures built to supposedly solve problems around the planet.

Interestingly, Dronestream creator Begley has apparently also devised an app that alerts users to drone-strike news, but has not been able to get Apple to approve it for inclusion in its App Store. The app is described as drawing on information from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which has its own data-presentation solution: an “interactive map.”

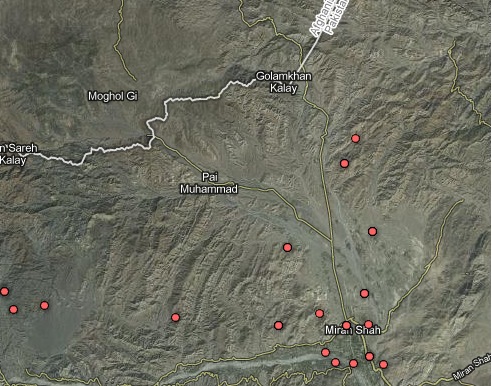

Screen grab of interactive map on Bureau of Investigative Journalism

Somehow interactive maps seem almost retro at this point. But I started poking around, trying to cross-reference the material there with a particular Dronestagram image, and was somewhat taken aback when I realized how many strikes had occurred in the same vicinity. I also realized that while I think each of these distinct approaches to making drone warfare more comprehensible has merit, what’s even more effective is considering them together. The more such projects can integrate with and reinforce each other, the better, I suspect, for all of them.