From Perspe by Gustav Willeit, via PetaPixel

A few months ago, I encountered some pictures created by Gustav Willeit. According to PetaPixel, Willeit creates “imaginary locations by mirroring landscape photographs and then adding in non-symmetrical elements into the images.” I rarely linger over landscape pictures, but these suggested to me a possible category loosely inspired by Bruce Sterling’s notions of “architecture fiction” and “design fiction.” I started collecting examples of landscape fictions: natural locations imaged, conjectured, altered by technology of some sort, or otherwise created.

Ultimately, the parrallel to Sterling’s terms was probably imprecise at best, and has become more so as I’ve played with the notion, for myself, over the ensusing months. These are less like landscapes that suggest fictions, and more like fictions imposed on landscapes.

Even so, the exercise has caused me to engage with a category of image that’s never really done much for me before. (That's true not just in the context of photography, which is the organizing principle here, but in real life: I have a distinct memory of seeing the Grand Canyon as a child and thinking, "It looks like a postcard.")

>In the middle of my collecting, as it happens, the winner of a recent “Landscape Photographer of the Year” competition was stripped of this honor after accusations of excessive fictionalization, via Photoshop. The photographer in question responded that he had not read the rules closely enough: “I have never passed off my photographs as record shots and the only reason this has come about has been due to my openness about how and what I do to my images. The changes I made were not major and if you go to the locations you will see everything is there as presented.”

Lindisfarne Boats, by David Byrne (not that David Byrne), via PetaPixel

The photographer's distinction of his work from "record shots" — even as he insists that "everything is there as presented" — seems useful.

The “landscape” makes me think of Ansel Adams, whose work always struck me being of interest mostly for technical reasons: Confronted with one of his prints, I start squinting at all the gray tones, looking for evidence (ironically?) of technical mastery and in effect ignoring the subject matter (pristine nature).

At the other end of the spectrum, Eszter Burghardt's landscapes are pure invention: a series of “miniature landscapes” made from “poppy seeds, coco powder, coffee, milk, and chocolate cake crumbs,” according to Junkculture.

No Cakewalk, from the series Edible Vistas, by Eszter Burghardt, via Junkculture

Adams’ landscapes can of course be read as fictions — mythologies, in Barthes’ terms, perhaps. The absence of fences, telephone poles, or other traces of the human-made now makes me think of one of Errol Morris’ points about photography: the hypothetical elephant that always might exist just outside the frame. (Thus the famous 1975 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, featuring the work of Robert Adams among others, and dealing explicitly the non-pristine, is often considered a sort of rebuke to Ansel Adams’ and many others' “Edenic” version of the West.)

Many of the examples I was drawn to involved meddling with the landscape in some physical way. Zander Olsen’s series, Tree, Line, is described as “constructed photographs rooted in the forest,” involving “interventions in the landscape,” specifically “ ‘wrapping’ trees with white material to construct a visual relationship between tree, not-tree and the line of horizon.”

Untitled (Cader), from Tree, Line by Zander Olsen, via OBlog

I Like This Art quotes Dan Bradica explaining that he photographs “temporary sculptures made from synthetic materials in managed forest preserves,” a practice that inolves “disrupting the natural environment” and results in a “depiction of the landscape that acknowledges the maintenance and control of civic land.”

From Constructions, by Dan Bradica, via I Like This Art.

Benoit Paillé’s series Alternative Landscapes involves the placement of a square-shaped light in various natural environments. (No Photoshop, reports Peta Pixel.)

“Untitled,” by Benoit Paillé, via Peta Pixel

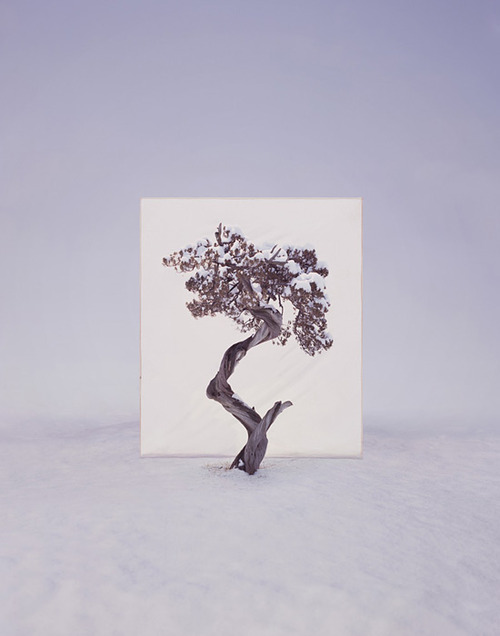

Myoung Ho Lee’s series, Tree, placed a canvass on the landscape — framing nature within nature.

“Tree #12,” by Myoung Ho Lee, via MuseumMuseum

One way of extending the interest in human-made structures on the natural landscape is to consider human-made structures as landscape. I'm thinking here partly of Edward Burtynsky, whose work in the documentary Manufactured Landscapes, capturing "industrial incursions" on the land and the systems behind them, is particularly notable. Here's a great interview with him from the amazing Venue project, which I suspect is in the process of adding a new and original chapter to the long history of considering what landscapes mean.

Burtynsky's work is revalatory in its documentation of systems. Christoph Gielen and others could be seen as pursuing something similar with aerial views of how the human-made and natural overlap. Thinking about what landscape fiction might encompass, I remembered this Granta piece about the Dutch government’s unusual method of blotting sensitive locations from Google satellite imagry: “imposing bold, multi-coloured polygons,” creating “sharp aesthetic contrasts between secret sites and the rural and urban environments surrounding them.” There's a system here, but it's not being documented, it's being mystified — fictionalized.

Staphorst Ammunition Depot, via Granta

Even before Apple’s Maps app became a glitch-art sensation/debacle, Clement Vella was collecting “strange snapshots” from Google Earth. These aren’t actually glitches but hybrid images,” Vella wrote on Rhizome.org, “a patchwork of two-dimensional photographic data and three-dimensional topographic data extracted from a slew of sources, data-mined, pre-processed, blended and merged in real-time.”

Via Rhizome.org

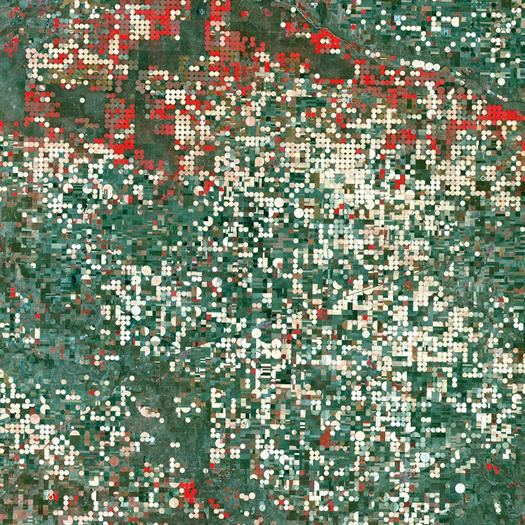

Just as I was putting this post together last week, I encountered another instance of what might be accidental landscape fiction: Slate highlighted satellite images compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey, for their aesthetic qualities. In this case, "center pivot irrigation systems" in Kansas evidently explain the unlikely patterns visible on the land only by way of the unnatural eye.

Garden City Kansas, by Landsat 7, from U.S.G.S. Earth As Art series, via Slate.

Nicholas O'Brien is a "net-based" artist, curator, and writer, and a good chunk of his work concerns landscapes. In 2011 he organized a show called "Notes On A New Nature," for 391 Scholes: "We use all forms of digital and analog technologies to simulate the natural world daily, and artists in this show point to how these tools affect the ways in which the 'realness' of the natural is no longer as simple as locating it outside your window."

While I'm interested in that, and now sorely wish I'd been able to see that show, clearly the landscape fictions I've been collecting take the technology/landscape notion in a direction that's not really about "realness," at least not in a visual sense.

I can’t remember how I came across this next image, from Jonathan Zawada: “The data that defines the shape of the mountain range is the cyclic repetition of the peaks and troughs of Google searches for ‘draft’ from 2004-2010.”

“O,” by Jonathan Zawada

Here is a good spot to mention that I am of course aware that "the landscape" pre-dates photography, and landscapes have been visually "fictionalized" by painters for a hundred years, in a hundred ways. On the other side of the spectrum, I'm also aware of the purely digital landscapes created for, say, video games.

But my particular framework for landscape fictions is photography — and while technology is relevant to the category, I think it's interesting how few of the examples here involve Photoshop. David Keochkerian’s surreal landscapes are achieved via an “infrared-sensitive camera,” according to PetaPixel.

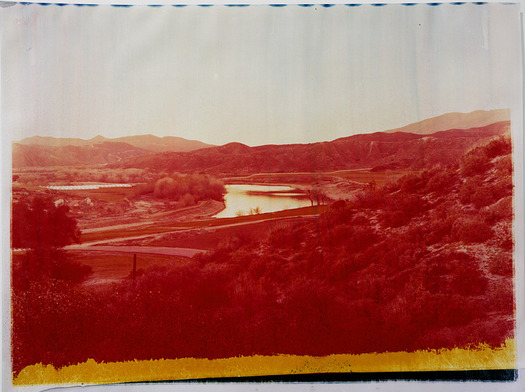

And finally: Matthew Brandt (subject of “well-deserved hype,” according to Coolhunting) has a series called Lakes and Reservoirs that involves soaking C-prints in water from the bodies he photographs, “for days or weeks or even months,” until the images attain their “desired look.” Like any number of the photographers whose photos I've collected here, he may well reject the attachment of the word "fiction" to his work: Here is a real image of (American West) nature, altered by interaction with a physical element of the very landscape it depicts. But to me the result of this imaginative process is nevertheless a kind of landscape fiction. And I think that response is only natural.

“Veil Lake, CA 2,” by Matthew Brandt, via Yossi Milo Gallery

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------N.B: I'll continue to collect examples of "landscape fiction" at LettersFromHere.Tumblr.com.