Most of us remember the first dead animal we ever saw — mine was a rabbit, killed by a car near my house. I touched it with a stick, moved its legs, and opened its mouth. While the earliest recorded human dissection took place in ancient Greece in the third century B.C. — the development of real, scientific knowledge of the human body has been excruciatingly slow. Not until the twentieth century did science and medicine finally begin to accelerate to magnificent heights. And now, at the dawn of the 21st century, we begin a new quest to map the human brain. The following anatomical images are visual examples of our long quest to understand what is inside the human body.

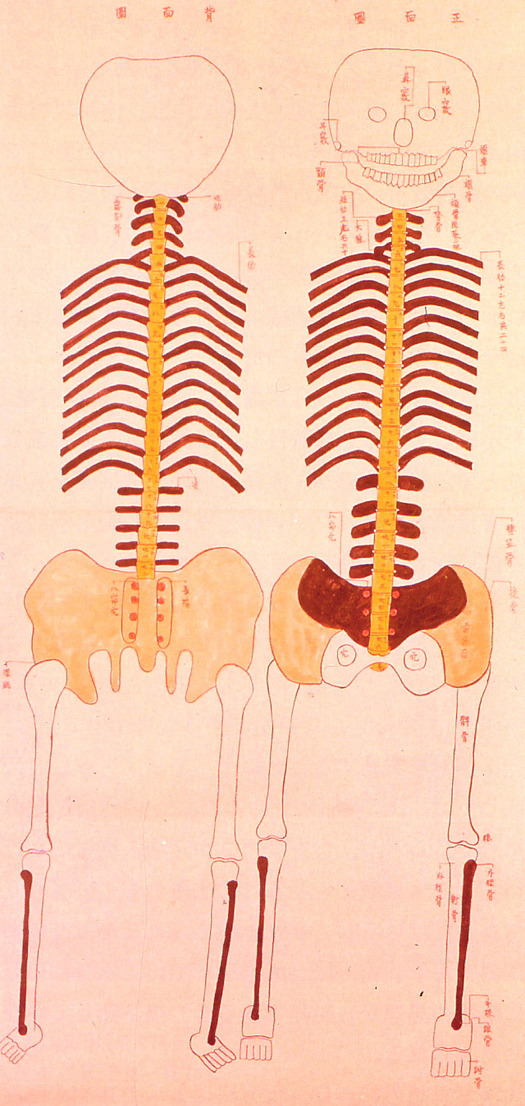

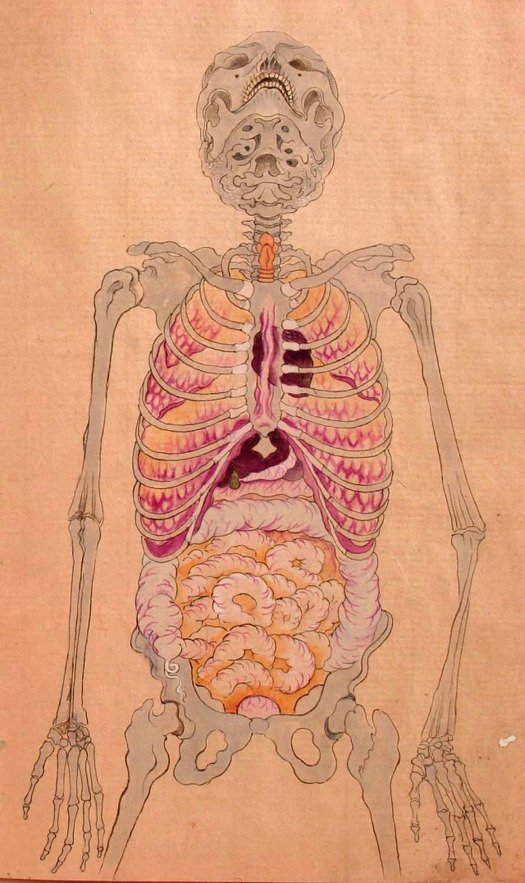

Human skeleton, 1732: This document is thought to have inspired physician Tōyō Yamawaki to conduct Japan's first recorded human dissection.

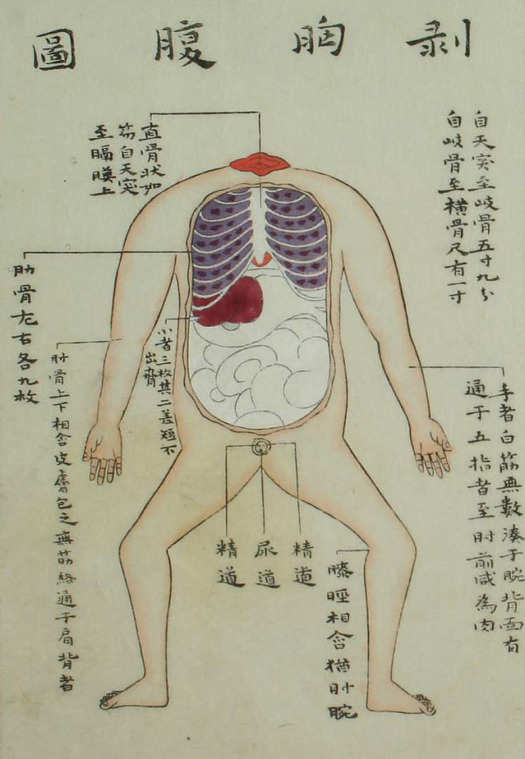

Illustration from 1759 edition of Zōzu: The actual carving was done by a hired assistant, as it was still considered taboo for certain classes of people to handle human remains.

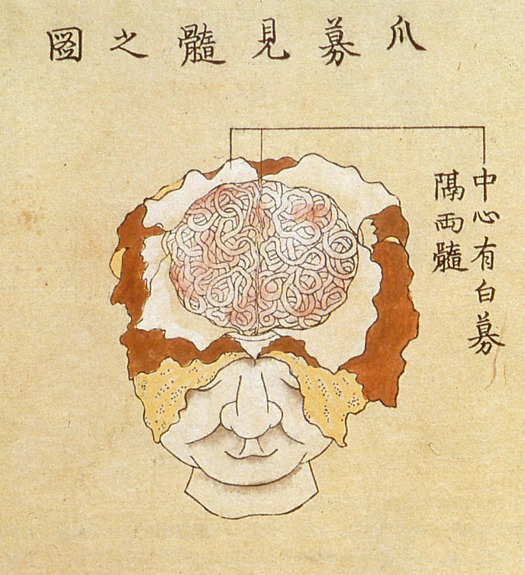

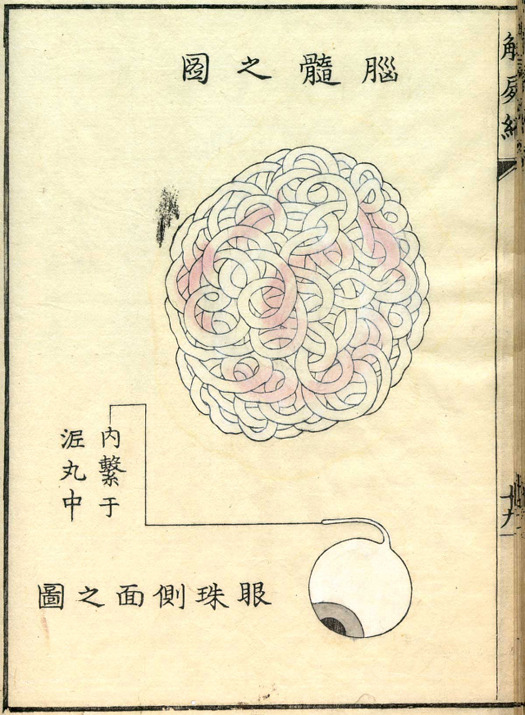

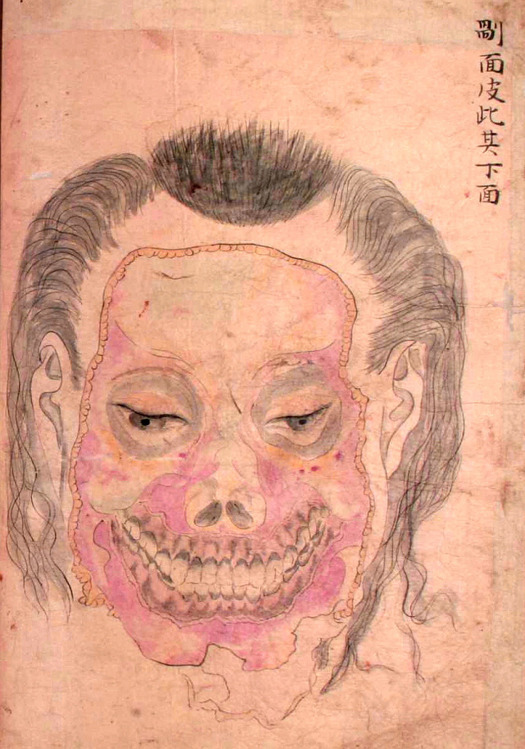

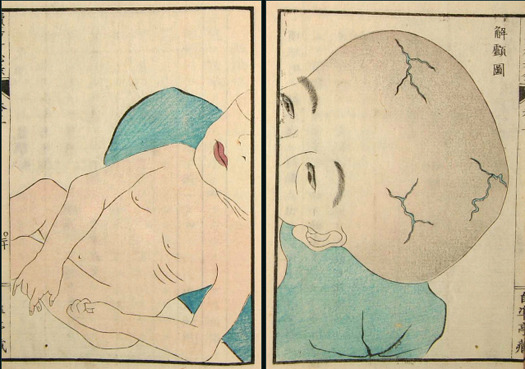

Kaishihen (Dissection Notes), 1772: Japan's fifth human dissection — and the first to examine the human brain — was documented in a 1772 book by Shinnin Kawaguchi, entitled Kaishihen (Dissection Notes). The dissection was performed in 1770 on two cadavers and a head received from an execution ground in Kyōto.

Kaishihen (Dissection Notes), 1772.

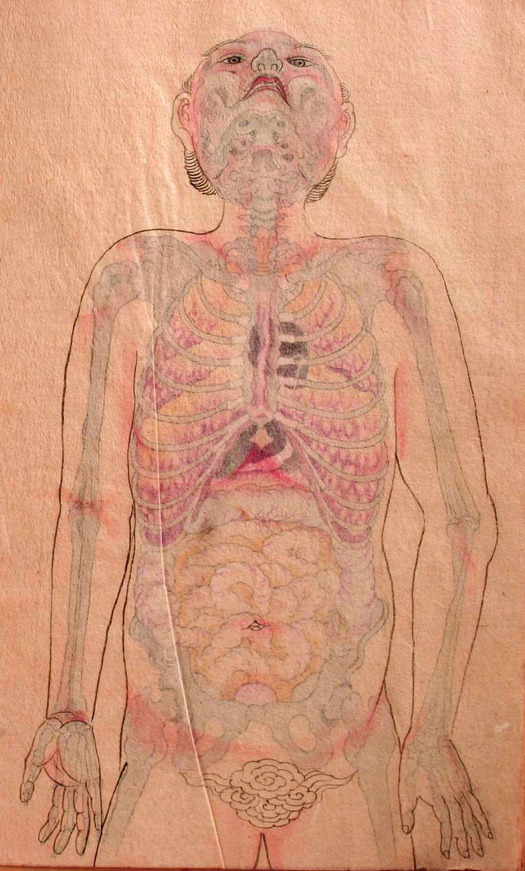

Human anatomy (date unknown): This anatomical illustration is from the book Kanshin Biyō, by Bunken Kagami.

Human anatomy (date unknown): In this image, a sheet of transparent paper showing the outline of the body is placed over the anatomical illustration.

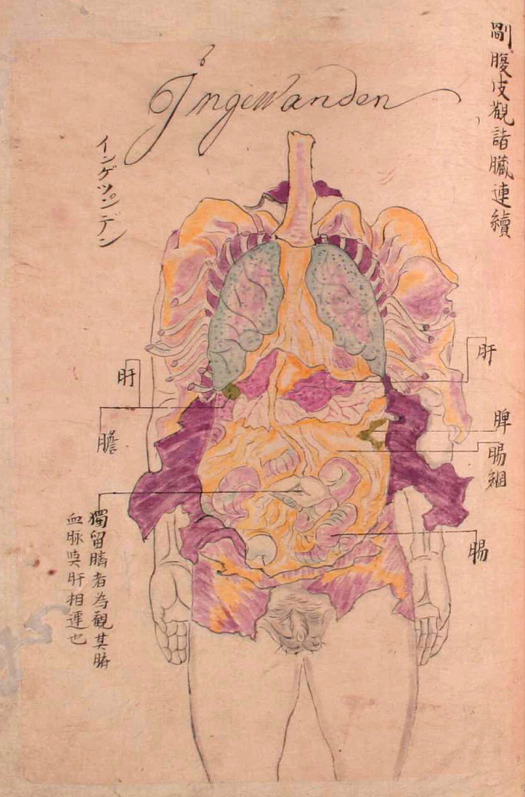

Seyakuin Kainan Taizōzu (circa 1798): These illustrations are from the book entitled Seyakuin Kainan Taizōzu, which documents the dissection of a 34-year-old criminal executed in 1798. The dissection team included the physicians Kanzen Mikumo, Ranshū Yoshimura, and Genshun Koishi.

Seyakuin Kainan Taizōzu (circa 1798)

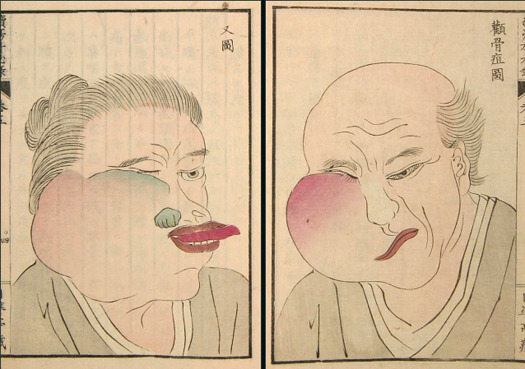

Zoku Yōka Hiroku (Sequel to Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), 1859. [Source: Nihon Iryō Bunkashi (History of Japanese Medical Culture), Shibunkaku Publishing, 1989.

Zoku Yōka Hiroku (Sequel to Confidential Notes on the Treatment of Skin Growths), 1859.

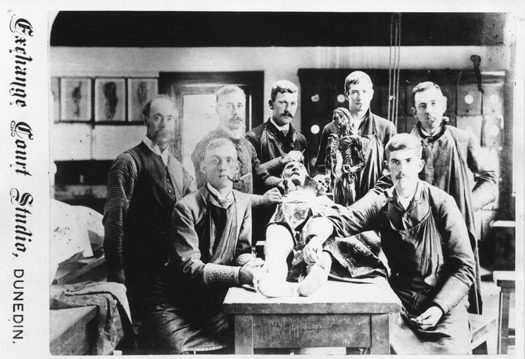

Anatomy dissection class, circa 1880.

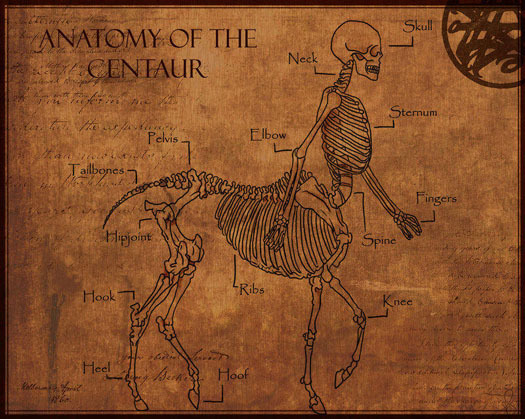

Anatomy of a centaur: Double lungs and the presumably also double stomach gives an explanation for the strength and perseverance of centaurs.

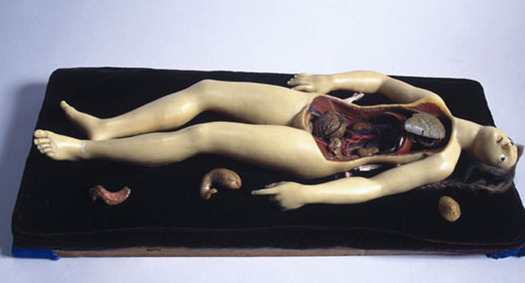

Full wax figure of female figure, 18th century.

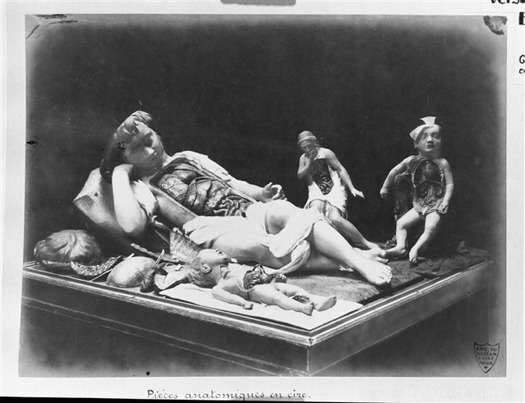

Photo of models from the Paris Museum of Natural History in the 1880s.

18th century wax model dissection from Florence, Italy’s La Specola Museum.

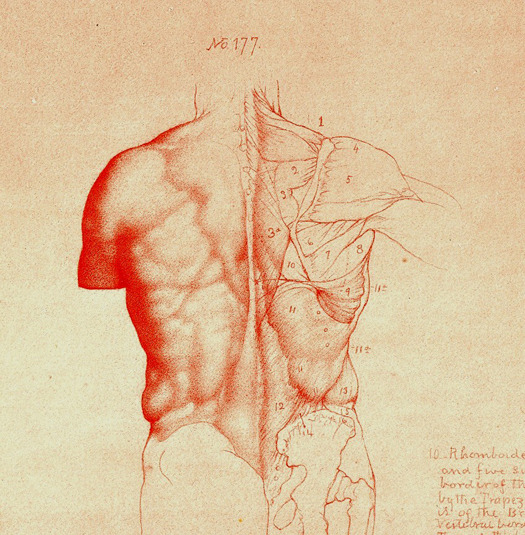

Anatomy drawing from William Rimmer's Artistic Anatomy, 1877.

Wax anatomical models at La Specola in Florence, Italy.

Wax models of human hand at La Specola in Florence, Italy.

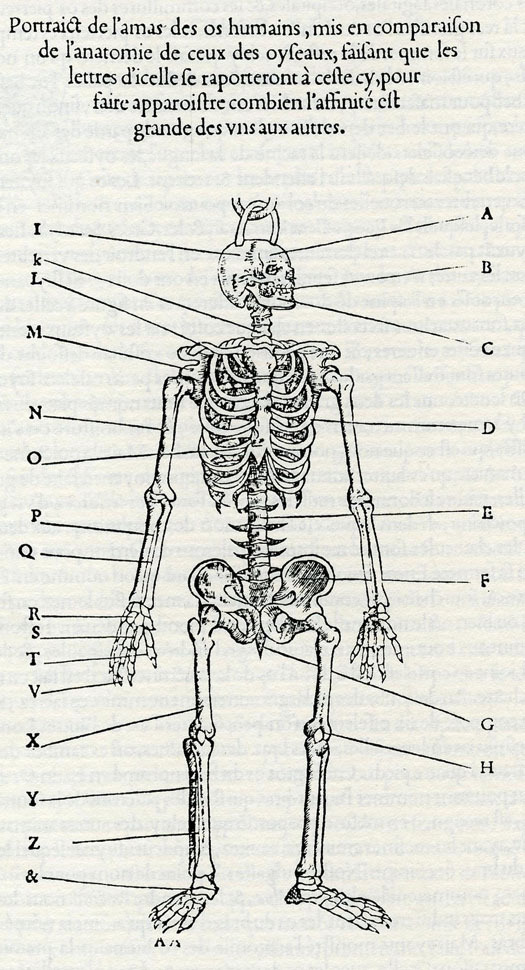

Human skeleton for comparison with that of birds. Pierre Belon, Nature des Oyseaux (The Nature of Birds), Paris 1555.

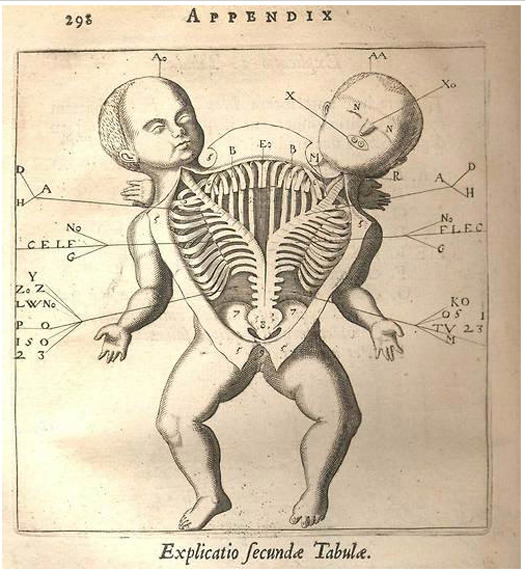

Anatomical drawing of a co-joined twin. Fortunio Liceti, De monstris, Amsterdam 1665.

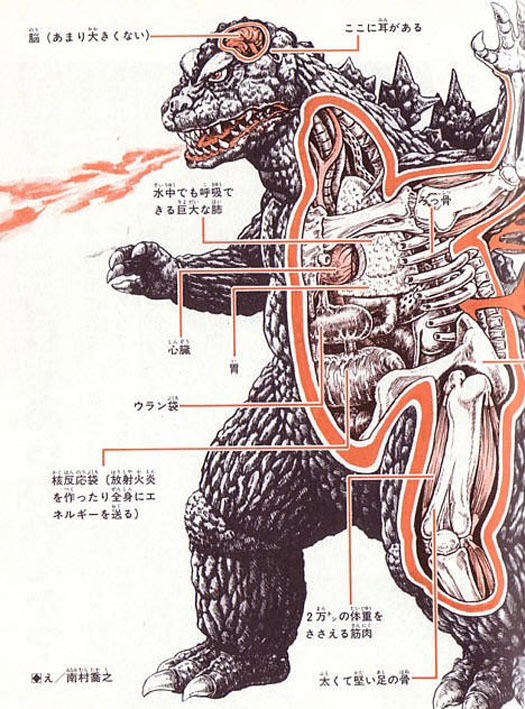

This anatomical sketch of Godzilla reveals a relatively small brain, giant lungs that allow underwater breathing, leg muscles that can support 20,000 tons of body weight, and a “uranium sack” and “nuclear reaction sack” that produce radioactive fire-breath and energize the body.

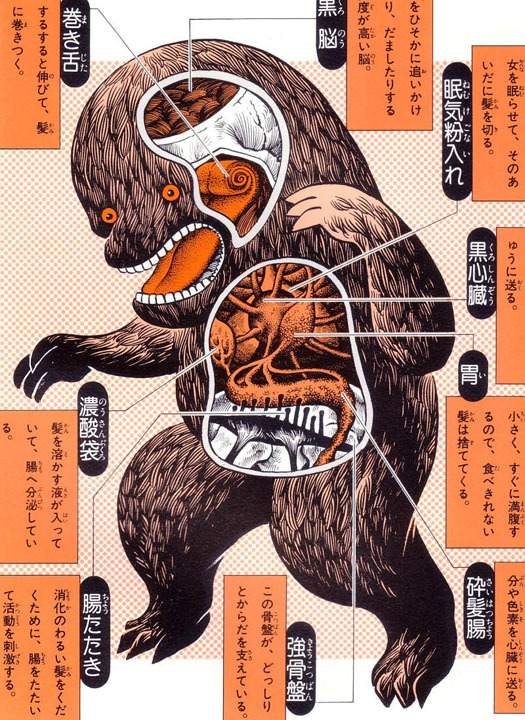

The Kuro-kamikiri (“black hair cutter”) is a large, black-haired creature that sneaks up on women in the street at night and surreptitiously cuts off their hair. Anatomical features include a brain wired for stealth and trickery, razor-sharp claws, a long, coiling tongue covered in tiny hair-grabbing spines, and a sac for storing sleeping powder used to knock out victims. The digestive system includes an organ that produces a hair-dissolving fluid, as well as an organ with finger-like projections that thump the sides of the intestines to aid digestion.

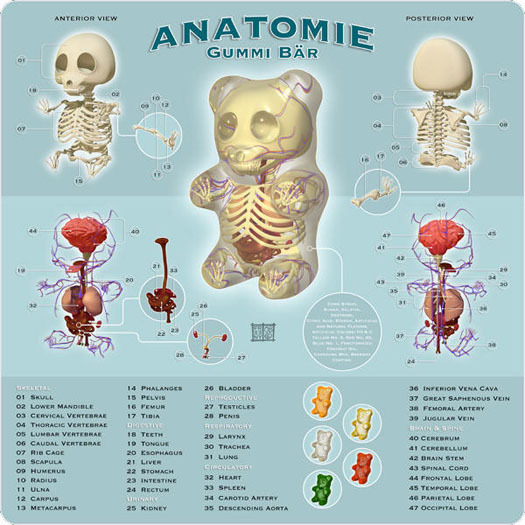

Anatomy of a Gummi bear, illustration by Jason Freeny.

Accidental Mysteries is an online curiosity shop of extraordinary things, mined from the depths of the online world and brought to you each week by John Foster, a writer, designer and longtime collector of self-taught art and vernacular photography. “I enjoy the search for incredible, obscure objects that challenge, delight and amuse my eye. More so, I enjoy sharing these discoveries with the diverse and informed readers of Design Observer.”

Editor's Note: All images are copyright of their original owners.

Editor's Note: All images are copyright of their original owners.