Fast Company has published its annual “design” issue, which includes a sort of timeline package of significant design-related trends of the past ten years. I was asked to chime in on “design rage:” online outbursts of discontent with, say, Tropicana’s packaging, a proposed Gap logo, and the like.

I bring this up not merely to promote my writing elsewhere, but because this is a subject that’s come up in various ways here before — I even quote from Michael Bierut’s memorable essay from earlier this year, “Graphic Design Criticism As Spectator Sport.” I’ve touched on “crowdcrit” in my own earlier posts, too, from a different angle.

In any case, you can check out the Fast Company piece as you wish, but it happens that there have been two more recent crowdcrit incidents since I wrote it that I think are relevant to the discussion of what it means when the online masses take an opinionated interest in design matters.

*

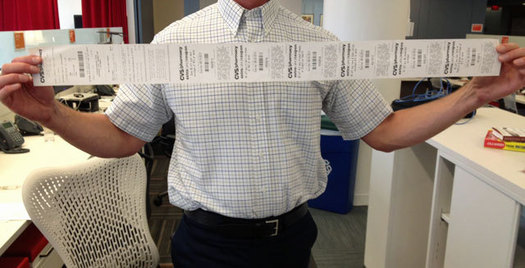

The first example involves receipts. A couple of years ago this was a bugaboo of mine: I really felt the whole idea of “the receipt” was ripe for rethinking. Specifically, I was getting receipts that were two feet long after buying just a few items from certain retailers. The reason? These retailers were tacking on all kinds of coupons and promotions — which struck me as flagrantly wasteful.

For a while, I researched and/or kept an eye on anything that involved redesigning/rethinking receipts. Perhaps they could go digital, be replaced by an app of some sort, or some other online service. The much-hyped team at Berg — “UI geniuses,” according to Fast Company, actually — offered a receipt redesign concept attempting to make them more useful and pleasing.

![]()

Neat. But as far as I know, none of the above has gone anywhere (including, obviously, my intent to write something on the subject, which I never did).

A few weeks ago, however, a crowdcrit response to ridiculous receipts broke out on Twitter. Its target was CVS, which had evidently become the most preposterous huge-receipt generator of all. For a fleeting moment, it became a social-media fad to mock its absurdly supersized receipts. At first CVS made a dubious claim that these objects were somehow eco-friendly, because they replaced other forms of coupons.

That defense rapidly crumbled. The chain capitulated, and promised to change what looks an awful lot like a wasteful practice.

AOL employee buys pack of gum at CVS, gets 38-inch long receipt. (Matt Brownell/AOL)

What matters here is that the crowd got results. I want to underscores that I’m saying this as someone who had mulled this very topic: I truly cannot imagine having written anything that would have such a tangible and immediate effect.

Kudos to you, Crowd.

*

The second example involves the more mundane matter of Yahoo!’s logo redesign. As some of you may know, I now write for Yahoo News, so I will offer no personal opinion about the company’s new logo.

But as many more of you know, this heavily promoted redesign attracted quite a bit of attention — a good bit of it negative, and much of it not very constructive. On one level this sounds like the crowd at its worst: Web-angry mob spews venom largely for the satisfaction of the spewing, etc.

Out of all that emerged this critique from Glenn Fleishmann. He addressed what he found objectionable about this redesign, for sure. But, more usefully, it seems to me that he used the crowd freakout as a prompt to deliver a thoughtful and passionate take on the nature of the design craft, and why it matters.

Again, I am not offering any personal opinion about his opinion, pro or con. But I think his general response here is instructive. If the crowd is worked up about something, even if it may be acting out in a way that borders on mindless, consider that an opportunity. Step into the fray to make a statement, one that simultaneously addresses the issue of the fleeting moment (this logo) and something bigger (why design should be taken seriously). Instead of lamenting what wasn’t being said, Fleishmann said something!

Without rehashing my Fast Company piece here, I'll just say there is some overlap. If you care about design, and you aren’t sure what to make of these mad outbreaks of “amateur” criticism covering the digital world like kudzu, then remember two things.

First, you can’t make it stop. Second, it’s not a threat, it’s a chance: Bit by bit, the audience for writing and thinking about design is growing. Maybe these crowdcritters don’t frame the discussion the same way you do, but you can’t change that, either. Instead, it’s up to you to frame what you want to say in a way that matches the rhythm of popular discourse.

Because the truth is, there has never been a better time to care about design.