John Foster: Hello, Bryon, and thanks for taking time to answer a few questions. I've had your site bookmarked for a few months now. I enjoy your photography a great deal, especially your series called “Modular City”. Personally, I have always enjoyed the way city streets are laid out — organized by engineers, architects and city planners. While city planners have always developed streets and neighborhoods to be orderly, there are still random factors they have to take into consideration, the most obvious being the terrain. From the air, there's such a beautiful randomness to cities. Would you elaborate on this and how you came about doing this extraordinary series?

Bryon Darby: Thanks, John! Really happy to hear you enjoy my work and have been following it for some time. I produced the Modular City series while a graduate student at Arizona State University. Like people often do, I was using Google Maps to explore my new surroundings and scout out potential sites to visit later with my view camera. One of the great things about attending a large MFA program like ASU is that one is continuously surrounded by active artists fully engaged in their practices — many of whom were truly pushing the boundaries of their mediums. Fellow grad students Nick DeFord, Ryan Peter Miller, and Peter Bugg, in particular, were hugely influential on my thoughts about art-making and photography. Their work was playful. They were using materials in new ways, finding inspiration in the ordinary, and they were asking questions that might be seen as undermining the very sanctity of their respective mediums. It also didn't hurt that they each had a healthy sense of humor. These and other experiences at ASU really opened my view on what could be done and what was fair territory. And, to cut right to the chase, it's all fair territory!

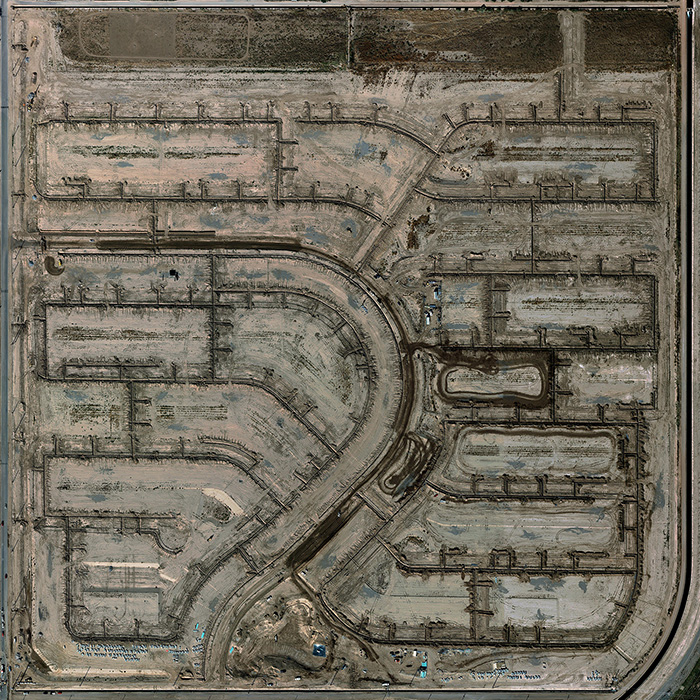

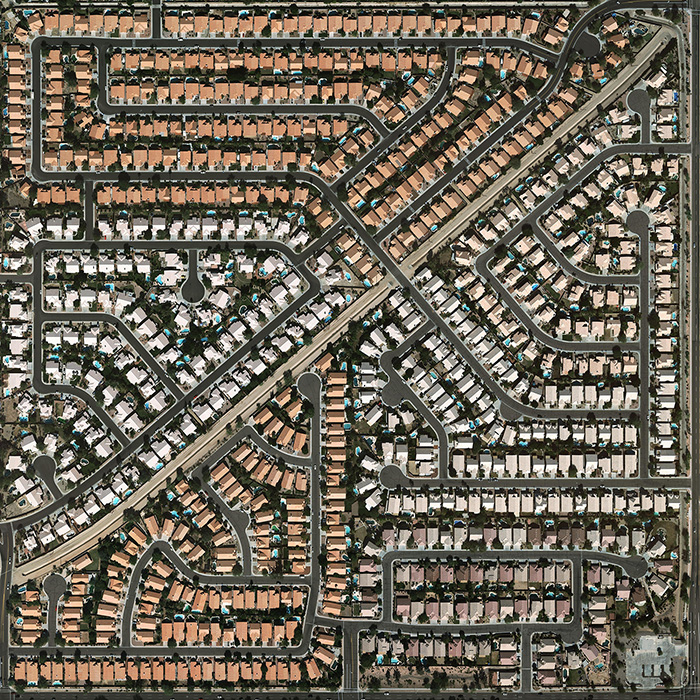

One day while scouring my neighborhood on Google Maps, it occurred to me that the act of exploring the terrain, choosing a vantage point, and framing a scene through a computer just wasn’t all that different from the way I was interacting with the landscape through my camera. In either scenario, the world is mediated through an electro/mechanical box and the content of the resulting “photographs” is in the selection process. When I began, I was making screen shots of aesthetically interesting blocks around my neighborhood. Growing up in Utah, I suppose I have always had a kind of penchant for the grid system of street layout and like so much of the West, Phoenix was originally laid out in 1/4 square-mile blocks. Over the years as development restrictions changed, those blocks have been creatively divided and sub-divided. Initially, I planned to digitally composite the screen captures into fabricated cities. But the more time I spent with them, the more I realized that the ideas I wanted to explore — land use, water use, development, class, socioeconomics — it was all right there. They needed no modifications. All I needed to do was present them as they were. So that is what I did.

JF: Since this comes from Google, what kind of print quality do you get when making prints?

BD: The initial process involved digital stitching of multiple screen shots. As I progressed, I figured out quicker ways of accomplishing the same task. As captured, I have enough resolution for quality (300 ppi) 20x20-inch prints. Typically, I exhibit them in 3x3 or 4x4 grids and have also exhibited them individually as 8x8-foot decals applied directly to a gallery floor. The quality is pretty high, but in either case, the prints exhibit some compression artifacts as would be expected from internet-sourced material. I just consider it part of the language of the web.

Modular City

A series of images appropriated from Google Maps depicting 20 half square mile blocks of the greater Phoenix metropolitan area.

© Bryon Darby

JF: You worked as a graphic designer for a while and then switched to photography after getting an MFA in photography at Arizona State University in 2011. How has your design eye informed your photography?

BD: I worked solely as a designer for only about a year after earning my BFA in graphic design in 2001. Though I took on freelance design work for many years, my primary focus has been photography since mid-2002. I suppose I have always worked with a sort of rigidity that lends itself well to design. I also work very systematically and embrace a process of make, evaluate, adjust, repeat. I put a lot of emphasis on the act of making and the importance of leaning through the work. I am also an object maker with fairly high expectations with regard to craft. I am sure much of these sensibilities were influenced by and carried over from my design background. As a professor at the University of Kansas, I currently teach photography to quite a number of graphic design students. My design students definitely see the world a little differently and I am often impressed with their ability to organize space and reduce the three-dimensional down onto a two-dimensional plane.

JF: You have created a few series on airplanes. What's your fascination with planes?

BD: I do have somewhat of a fascination with airplanes. It's hard not to marvel at a 875,000 pound hunk of of metal flying through the air at 600 miles per hour. Also, despite the fact that I fly quite often, I have a pronounced fear of flying that seems to only heighten my borderline-obsessive interest in airplanes. But in truth, that work came not from an interest in flight but rather a response to place. At the time I was living directly within the flight path of Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport. Living in Phoenix, I was stuck by the magnitude of flight traffic. Below the flight path there is an almost constant roar of engines. Every few days I would even find myself in the sudden blink of an aircraft's shadow hurling across the pavement at 175 miles per hour as it approached the landing strip. I was trying to make work that spoke to the experience of living there and airplanes were an integral large part of that experience. It was also very productive work, so I kept with it.

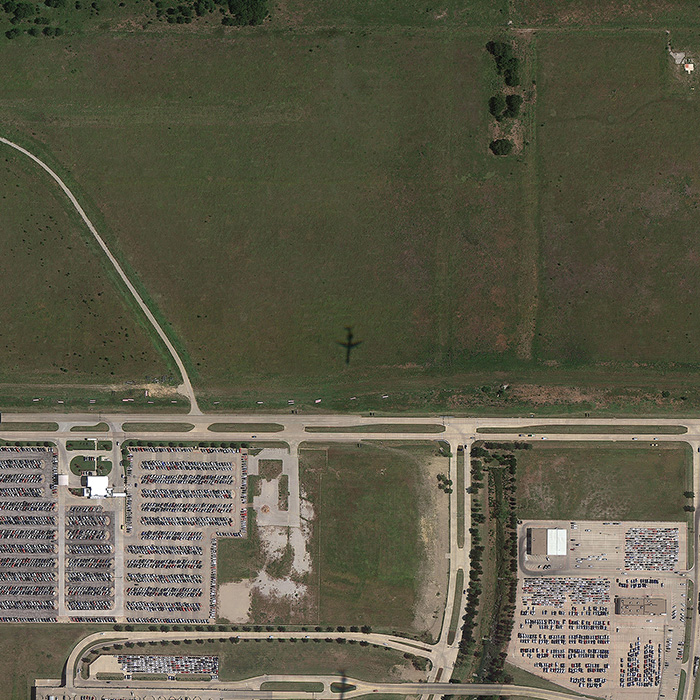

JF: With the series “On Approach” you have images of airplanes in flight from directly above. Are these from Google Maps as well? Did you search flight paths at airports in order to find these?

BD: Yes, those images are also gathered from Google Maps. While pursuing maps I stumbled upon a jet approaching the Phoenix airport. I quickly looked to see if I could find other Google-captured planes near airports. Turns out, it's not that uncommon. If you look around the flight path at any major airport on Google Maps, you'll probably find an airplane or two.

On Approach

A series of images appropriated from Google Maps that showcase the flight paths of airplanes all over the globe.

© Bryon Darby

JF: With your series “Persistent Aircraft” you take a different perspective—you are on the ground looking up. Plus you switched to black and white. Could you elaborate on this series?

BD: Much of why the flight path work was so productive for me is because I could continually switch up my methods and speak about the experience in a new way. While the "Seventy Flights in Ninety Minutes" composite speaks to the volume of air traffic in the Phoenix area, the "Persistence" series speaks more about, well, persistence – the idea that those aircraft are embedded into the very fabric of that particular place. The work was made with a hand-held medium format camera over the course of just a few hours. I stepped out onto my front porch, drove along my usual route, and took pictures of planes as I saw them. The choice to use black and white was motivated mostly by familiarity with and cost of materials. However, I do like the resulting stark, graphic quality. This same approach was expanded over a 5-day period resulting in the "Encountered Aircraft" book and series.

Persistent Aircraft

A series of images photographed by camera from the ground in and around the flight patterns of the Phoenix airport.

© Bryon Darby

JF: Finally, what’s next for you? Any exhibitions or books coming up to watch out for?

BD: I have an incredible amount of work on the back-burner that I haven't found the time to finalize. I have returned to Phoenix a few times to finish up unresolved ideas – including a 9-hour, 9-panel flight path panorama. Last summer I had a residency at the Center For Land Use Interpretation in Wendover, Utah. The work I made was centered around the historic airfield and its current primary use as a landing pad for casino junket flights. Much of the work that resulted from the residency is currently on display at the CLUI Exhibition Hall in Wendover. I have also just begun a new project related to farming with a collaborator here in Kansas. We'll see how it goes!

JF: Thanks for your time Bryon.

BD: Thank you, John! I really appreciate it.

This interview was originally posted in July 2014.