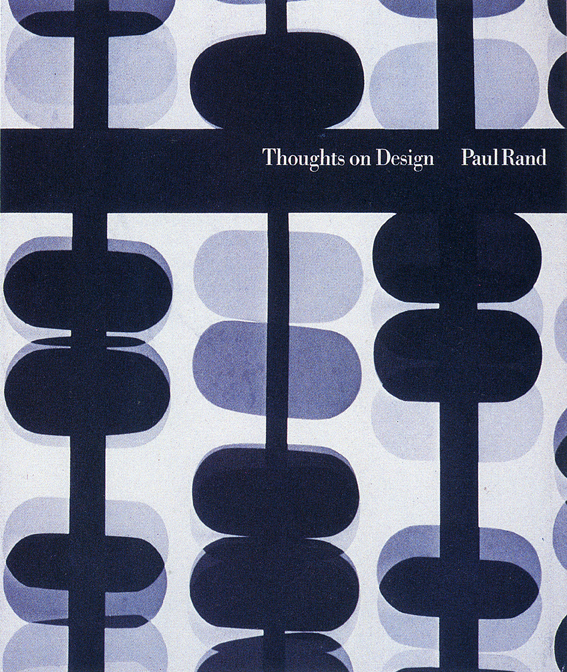

On one of my first trips to New York in the 70s, I was in the bargain basement of a large chain bookstore on Fifth Avenue when I saw a tall stack of square books, so clean and abstract it was almost a piece of sculpture. It was the third edition of Thoughts on Design by Paul Rand. Unbelievably, they were selling for a dollar. Even more unbelievably, I only bought one.

When Paul Rand sat down in 1947 to write the book that would become Thoughts on Design, he was 33 years old. The designer, born in Brooklyn as Peretz Rosenbaum and largely self-taught, was already a sensation. Appointed chief art director at the fledging advertising agency William H. Weintraub & Co. just six years before, he was credited with revolutionizing the clichéd and buttoned-down world of Madison Avenue by introducing the bracing clarity of European modernism. The effect was startling and immediate. Rand’s signature appeared on book covers, posters, and ads. Classified ads looking to hire designers began specifying a “Paul Rand type.” No one needed to ask what this meant.

Despite this sudden fame, Rand’s career had barely begun. His logos for IBM, Westinghouse and ABC Television — all would be incorporated in the book’s subsequent editions — were still in the future. So were his induction into the Art Directors Hall of Fame, his receipt of the AIGA Medal, his position on the faculty at the Yale School of Art, and all the awards and accolades that would establish him as his country’s greatest graphic designer by the time he died in 1996. 33 years old was, perhaps, early for a book, but Rand was ready.

Paul Rand admitted all his life that he was insecure as a writer. It was his passion for his subject — the power of design and its capacity to contribute beauty, intelligence and wit to everyday life — that made him such an effective one. In his day job on Madison Avenue, he had learned the virtues of saying more with less. As a result, Thoughts on Design is almost as simple as a child’s storybook: short, clear sentences; vivid, playful illustrations. It is only 96 pages long.

Ostensibly, it is nothing more than a how-to book, illustrated with examples from the designer’s own portfolio. But in reality Thoughts on Design is a manifesto, a call to arms and a ringing definition of what makes good design good. This, perhaps, has never been said better than in the book’s most quoted passage, the graceful free verse that begins Rand’s essay “The Beautiful and the Useful.” Graphic design, he says, no matter what else it achieves, “is not good design if it is irrelevant.”

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy once said of Paul Rand, “He is an idealist and a realist, using the language of the poet and business man…He is able to analyse his problems but his fantasy is boundless.” He would go on to write other books, but that balance between passion and practicality was never displayed better than in Thoughts on Design. Its message is still relevant. Nearly 70 years after its original publication, it remains, for me, the best book ever written about graphic design.

This essay is adapted from Michael Bierut’s foreword to the 2014 edition of Paul Rand’s Thoughts on Design, published this month by Chronicle Books.