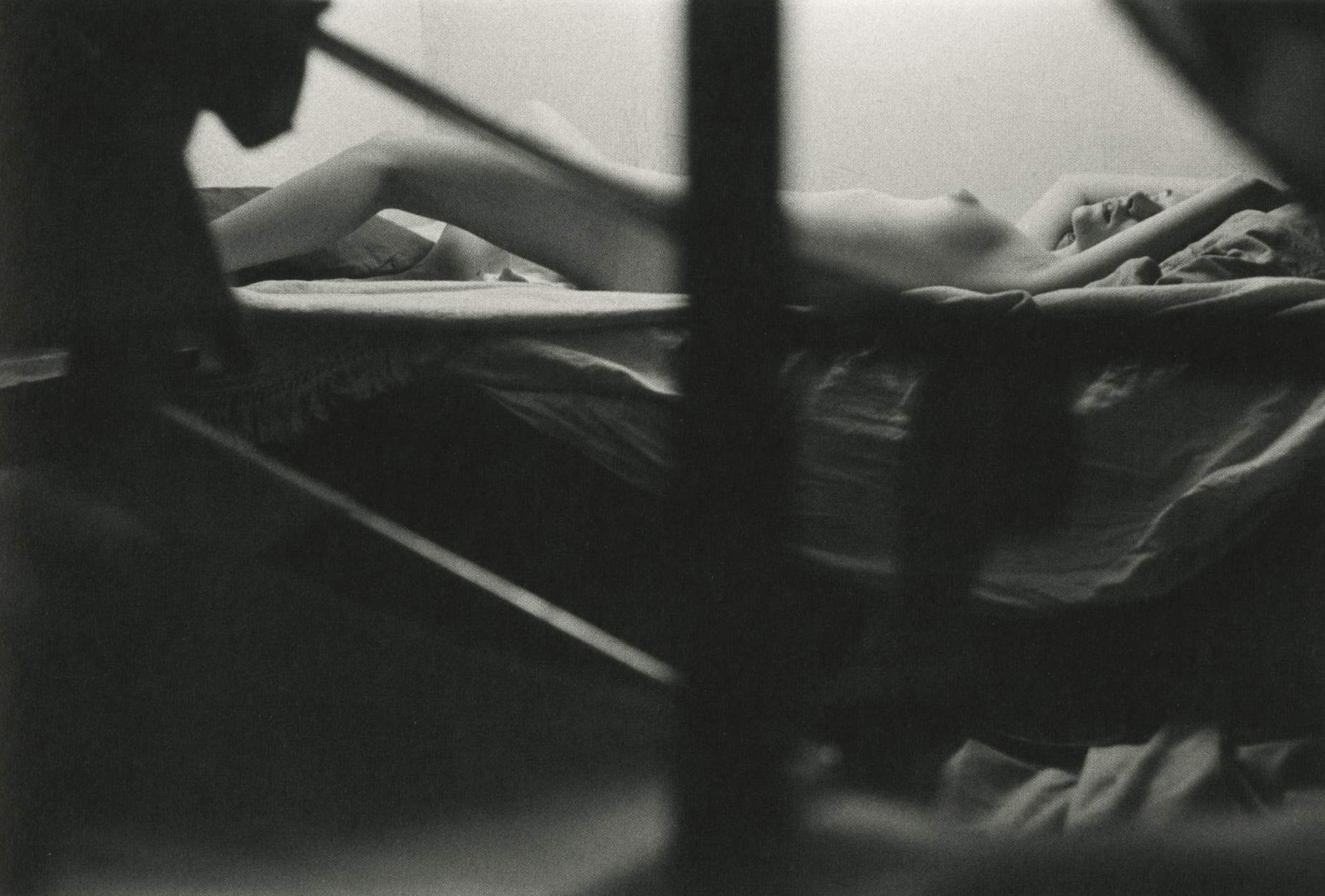

Fay, 1958

His work is compositionally innovative and psychologically astute. His distinctive eye for mirrored reflections, fragmented frames, and enticing bodies is clearly evident. His work in black and white is as significant as his work in color.

Many of these photographs are powerfully emotional: the nudes exude a compelling sensuality and the portraits are a complicated mixture of observance and empathy.

Jean, 1948

I can’t be objective about this work. After publishing a short profile of Saul on Design Observer, I began to visit him at his East Village apartment twice a month for about three years. Those visits were humorous and intense, strange yet reassuring. He was my mentor, confidant, and friend. But he could also be critical and cruel.

Our conversations often went deep. The photographs of his father, his mother, and in particular, his sister Deborah, come freighted with stories: a weighty legacy of broken expectations (his father’s) as well as with pain and loss. His sister glows in these photographs with heartbreaking beauty and promise.

Deborah, c. 1947

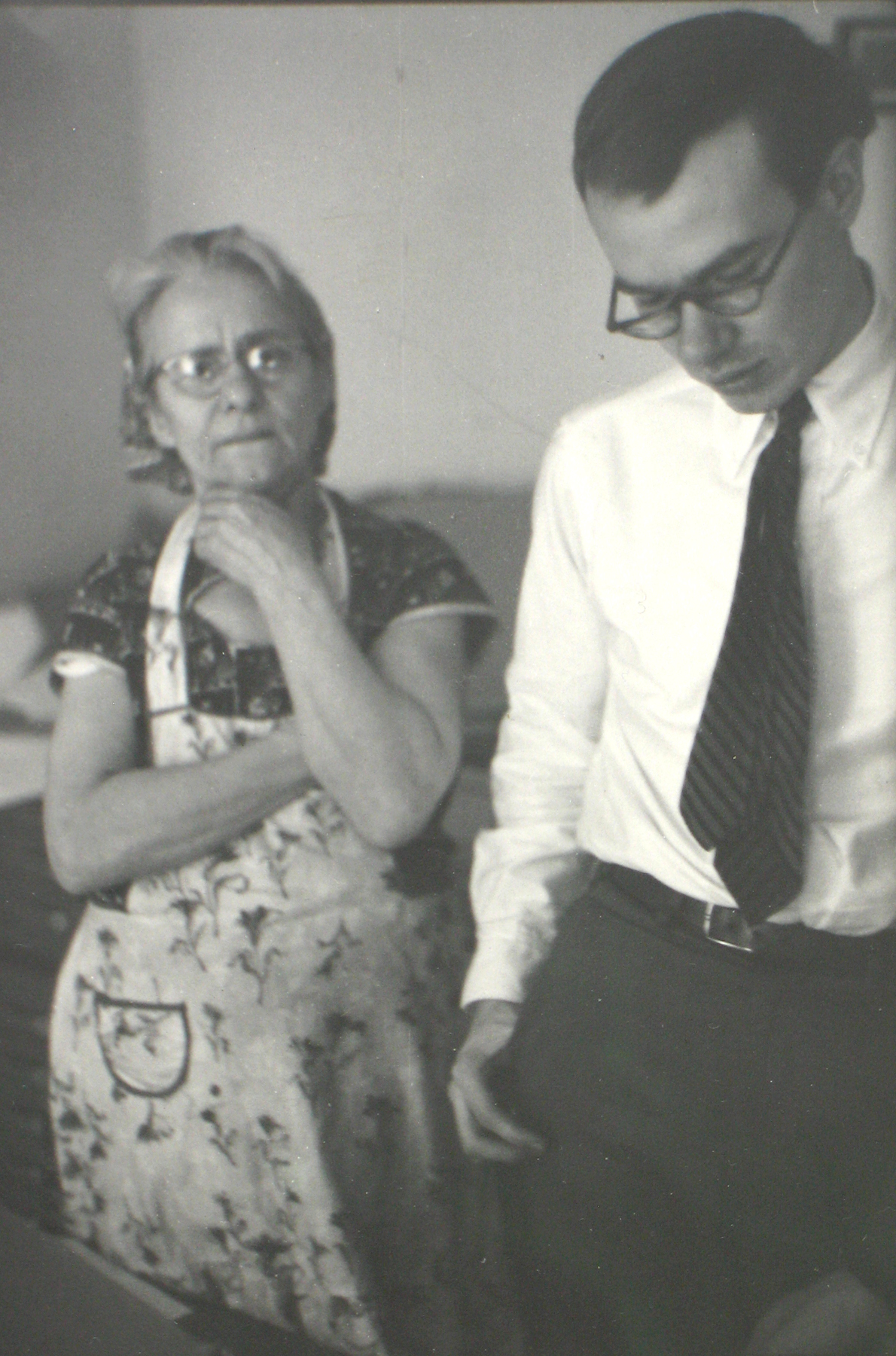

There are glimpses here of people who will raise art world eyebrows: Marcel Duchamp, Diane Arbus, John Cage, Andy Warhol. But these are anything but star struck pictures; we see Duchamp’s back, Warhol as a yet-to-be-famous waif with his mother, Cage intent during a rehearsal: semi-private, intimate moments. “The art world is a funny business,” he said to me. “It’s the perfect place for phonies.”

Andy Warhol and his mother, 1950

Saul stubbornly stayed on the periphery of the art world and as a result he was forgotten for nearly forty years. And yet, remarkably, his life did momentarily intersect with some of the great artists of his time: Willem De Kooning, for example, admired his paintings, Garry Winogrand admired his photographs, and Robert Frank would give him an affectionate squeeze when they bumped into each other on the street.

It’s a misrepresentation to categorize Saul as a loner, although, later in life, he preferred the company of a few close friends to bustling social occasions. He was more expansive in the late 1940s. In the photographs of Richard Pousette-Dart we catch the enthusiasm of a new and budding friendship. Given his family background, and his temperament, he was attuned to the undercurrents in the lives of his friends and he inevitably captured their emotional intricacies.

Dick and Adele, 1947

And then there are the women: languorous, inviting, and challenging by turns. They are almost always achingly beautiful and enticingly sensual.

Fay Smoking

His nudes are never predatory. What makes them compelling is how complicit these women are; they seem to be collaborating in his process of taking a photograph of them. They stretch and curl and smoke, mostly in bed, and they show us who they are, unadorned.

I would often see these photographs scattered about his apartment. His tables were stacked with books and bills and watches and pens, and often a photograph of Fay or Barbara or Inez would peek out from under one of the teetering piles, a surprising and tantalizing glimpse of sensuality.

The piles shifted from week to week as he burrowed to retrieve a monograph or fish out an old letter. So the photographs would churn as well, like lava bubbling up to the surface and then sinking back down.

When one of these photographs would emerge into sight, he would often talk about these women: an inner history of love and despair. Some were lovers, but by no means all. One was the daughter of a close friend, one was a model, another was the wife of a friend who would occasionally show up at his door late at night, seeking consolation from her difficult marriage, and with whom he never slept.

But some of the most evocative images are of women with whom he did share a bed. In particular Barbara, who is a captivating and unforgettable: a subtle mixture of fragility and strength.

Barbara, 1951

His nudes go beyond carnal desire and touch something more lasting and mysterious. Deeply versed in the traditions of Western painitng, he aimed, in his humble yet ambitious way, for the universal: “I search for a bit of beauty here and there,” he once told me, “and I’m pleased when I find it.”

Editor’s Note: Early Black and White is a two-volume set. This post is about Volume I: Interior. A second post will discuss Volume II: Exterior.

The exhibition Saul Leiter runs September 18–October 25, 2014 at Howard Greenberg Gallery

All images © Saul Leiter/Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York