What does it mean to mourn in the modern world? I raised this very topic when I was invited to speak to the designers at Facebook several months ago. And I have not been able to forget it.

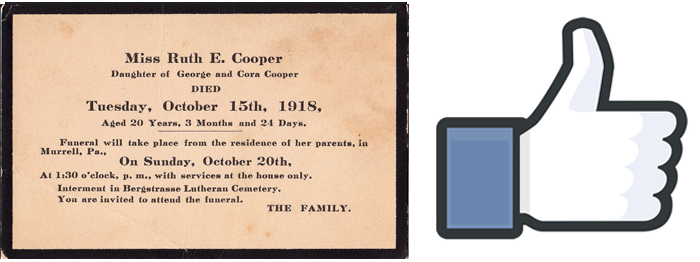

When a death is announced on Facebook, the only way to express sympathy is with a “like” button. The visual and emotional limitations of this practice are staggering, not only because our technological sophistication sits so far from our human (yes, communicative) capacity to express complex emotions, but because we lack the visual vocabulary for doing so. Even, and perhaps especially, online.

And what does the thumbs-up emoticon actually mean, here? I like that you shared this? I feel your pain?

True, the custom of sending black-bordered condolence notes through the post may seem ridiculous to the time-pressed denizens of social media communities. Yet as antediluvian as it may seem, this classic social ritual succeeded because it was governed by a simple, and rather brilliant, design conceit. Instantly readable—a simple black border connoting death—it immediately telegraphed the purpose and poignancy of the information it contained: someone has died, and now you know it. You might, upon receiving this news, experience any of the following feelings: sympathy, empathy, sadness, grief. You “liked” none of them.

These are sentiments that benefit from a patient heart, begging the question: can grief be processed, compacted, made into an icon? Put another way: how is it that we have progressed this far without a common visual vocabulary capable of expressing sadness?

Perhaps this shows us the limitations of icons. (Designers: take note.)

There’s something morally absurd about this topic, particularly when you consider that a quick online search for mourning stationery turns up some quick results on Etsy, where it’s being marketed as fodder for Halloween party invitations. Am I being sentimental? Perhaps. But none of us are exempt. Death, eventually, awaits us all.

Go ahead, if you wish, and “like” this post. But next time you learn of the finality of someone else’s life, think, for just a moment, before you minimize the enormity of that passage by clicking on a link—let alone one with a thumb in the air. Make no mistake: death is a part of life and condolence is not only a necessary act, it is a social one. It does indeed take a village, and I, for one, am grateful for mine. (I speak from personal experience here.) There simply must be a better way to visualize it on screen.