Everybody loves an underdog. Especially if the underdog is the woman who wrote the screenplay of Rocky (under the pseudonym Julia Sorel), is the author of five novels and is an Obie award winning playwright, and, wait for it, was once a championship female wrestler (under the name of Rosa Carlo “The Mexican Spitfire”).

She is also an extraordinary, but overlooked, Pop artist.

Her current show at the Garth Greenan Gallery is a barnburner. There are jabs of sex and violence, a flurry of exquisite miniature collages, and at least two bare knuckle left hooks.

Marilyn Pursued By Death (1967) is the most powerful. It exemplifies Pop: appropriation of image and a fascination with popular culture delivered with the graphic punch of advertising. In 1963 Drexler was clearly in the ring with the big boys, emergent Pop artists like Warhol and Lichtenstein, but her work is more painterly, less shiny and machine-tooled.

In the painting, two figures race across a void, mirror images of each other: white shirt, black pants, sunglasses, their bodies outlined in a vibrating red line. Who is Death? A paparazzi is one guess I heard while visiting the gallery. Lee Strasburg, Monroe’s acting guru (whose influence, along with his wife Paula, is often cited as the trigger for Monroe’s artistic and psychological demise), was another. In a 2007 interview, Drexler says the scene originates in a photograph taken in June 1956, on a day when Monroe and Arthur Miller were pursued by reporters while driving to Miller’s home in Roxbury, Connecticut, where they were to hold a press conference announcing their upcoming marriage.

One of the cars, driving at speed on a twisty country road, lost control and crashed into a tree. The New York bureau chief for Paris Match, Mara Scherbatoff, was thrown from the vehicle and lay dying in the road. Monroe fled her car and was followed by her bodyguard (unbelievably, there is footage of this, including a brief shot of Monroe bolting from the car). The accident was an ominous foreshadowing of what turned out to be a disastrous marriage. It was an even greater foreboding of the deadly relationship between the press and celebrity that reached its apotheosis in Princess Diana’s death in another car pursuit forty-one years later.

But Drexler’s Marilyn Pursued by Death isn’t reportage, in fact it’s just the opposite. Drexler slices the image from the news, drains it of realism, and sets it aglow with almost mythic significance.

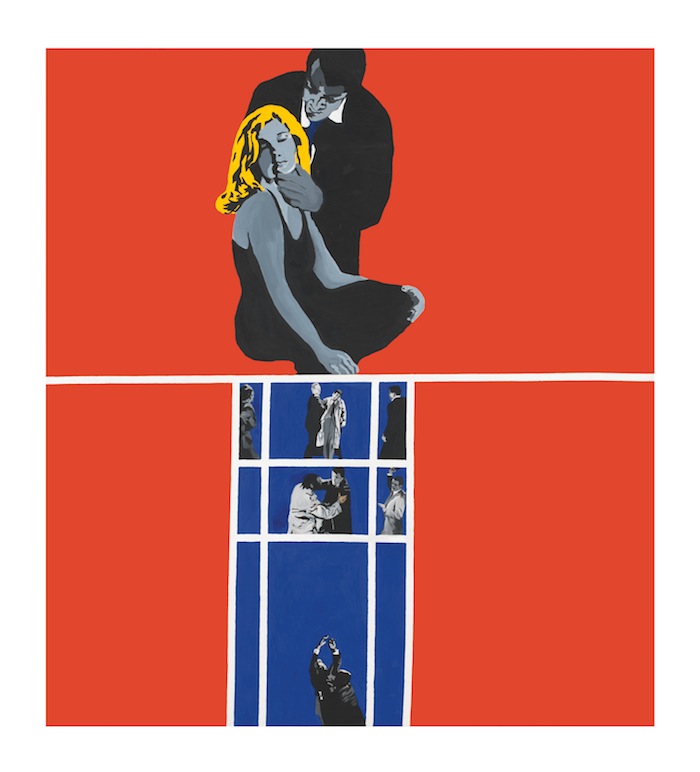

Love and Violence (1965) is another example of Drexler’s ability to montage sex, violence, and the movies, and lift her images above the quotidian plane. Super saturated colors highlight the movie-frame-like stills. In the top half of the painting, love seems to be about the desire to dominate, and a reflexive refusal to submit. Down below violence is an intimate struggle, a pas de deux performed to the rhythm of death. Are love and violence both of these things, one shot following the other, the two frames combining to make a whole?

Drexler offers no solutions, but clearly delights in posing defiant questions. She challenges boundaries by intercutting the vulgar with the sublime.

Rosalyn Drexler: Vulgar Lives is on view at Garth Greenan Gallery in New York until March 28.

© 2015 Rosalyn Drexler / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York