The savagery, intimidation, and horror of the recent decapitations by the extremist rebel group Islamic State have been transmitted via social media and television to the entire world. They cannot be justified or excused. But at the same time we shouldn’t ignore the fact that beheading is a powerful visual metaphor that runs deep within Western culture. It saturates our myths, religion, politics, and art.

What follows is a highly subjective visual history.

++

Caravaggio’s Head of Medusa

The myth of Medusa

Medusa was one of the three Gorgons and the only one who was mortal. She had serpents for hair and a face so ugly that “all who gazed at it were petrified with fright.” One look from her turned the gazer to stone.

Perseus promised to cut off Medusa’s head to stop Polydecetes from marrying his mother. Athena overheard his vow and, being an enemy of Medusa’s, gave Perseus a polished shield so that he could see Medusa’s reflection without risk of being turned to stone himself; Hermes gifted him a sword made of hardened gemstones.

Perseus eventually found the Gorgons asleep, “among the rain worn shapes of men and beasts that had been petrified by Medusa.” He used the shield to find her reflected image, swung his sword with Athena’s help, and decapitated her in one stroke.

Is this not one of the objectives of the IS: an attempt to turn us into stone, to literally petrify us with fear?

Michelangelo’s David and Goliath on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

David and Goliath

In another canonical Western narrative of a decapitation, stone plays a pivotal, yet far different, role. Goliath, supreme fighter of the Philistines, steps out from behind the line of battle twice a day to challenge the Israelites. He dares them to send out a fighter for a one-on-one battle that will decide the outcome of the war.

David takes up the challenge and declares, “I will strike you down and cut off your head.” He picks up five smooth stones from a brook and puts them in his shepherd’s pouch. David confronts Goliath, the two exchange declarations and threats. David approaches the battle line, slips his hand into his bag, takes out a stone, and slings it at the Philistine. “The stone sank into his forehead,” and Goliath topples over. He lands face down and David uses Goliath’s sword to cut off his head.

It hardly needs to be said: the IS’s use of video footage is slung at a well-armed Goliath, a stone aimed at a giant’s forehead.

Gentileschi's Judith Slaying Holofernes

Judith and Holofernes

Blood and lust. In the apocryphal Book of Judith, the Jewish heroine (“beautifully formed and lovely to behold”) sets herself the mission to stop the Assyrian general Holofernes from destroying her hometown of Bethulia. She removes her widow’s mourning clothes, bathes, and anoints herself with ointment. She adorns herself with a tiara, bracelets, rings, earrings, and anklets. She gives her maid a skin of wine, a flask of oil, dried fig cakes, and loaves of fine bread to carry, along with some utensils. Together they set off.

They cross a valley and are stopped at an Assyrian checkpoint. Declaring that they have useful tactical information, they are shown to the Generals’ tent. On seeing her, Holofernes is “beside himself with desire for her. He trembled with passion and was filled with an ardent longing to posses her.” She gets him drunk and he passes out.

With her maid standing by her side, she takes the sword that hangs from his bedpost, grabs his hair, and with two strong strokes, chops off his head.

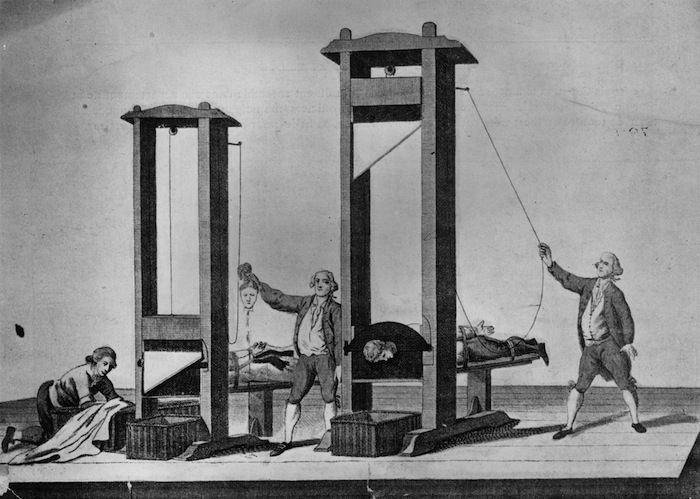

A French engraving depicting a guillotine at the time of the Revolution

The French Revolution

During the third week of August 1792, a device known simply as The Machine, or the guillotine, was set up in front of the Tuileries at the place du Carrousel. It represented a new method of industrialized killing, a far more efficient means of execution than the previous processions, elaborate spectacles, and drawn-out deaths by hanging or being broken on the wheel.

This new technology was presented to the National Assembly by Joseph Guillotin, who portrayed it as a humane form of capital punishment that was democratic. The Machine knew no class distinctions: the common criminal was executed in exactly the same way as the nobleman. “The mechanism falls like thunder; the head flies off, blood spurts, the man is no more,” he was reported to have said.

It was left to a member of the Academy of Surgeons, Dr. Antoine Louis, and a German harpsichord maker, Tobias Schmidt, to build the first prototype, which was tested on corpses. Finding it successful, the guillotine became the technology of choice as the Jacobins ruthlessly eliminated their opposition. At its most efficient, twelve heads could be decapitated in five minutes. The Machine also became known as The National Razor. It sheared the heads off approximately 17,000 people.

In the town of Lyon blood gushed so plentifully from under the scaffold that citizens complained that the drainage ditches were overflowing. The French Republic was born in a river of blood.

Terrorism is not a twenty first century phenomenon; the word was first used in 1795 to describe this critical moment in European history. Terrorism is not just about “them,” it is also about us.

Marc Quinn, Self (Blood Head)

Self Reflection

Made from eight pints of the artist’s own blood, Self is an auto-decapitation, an artwork that takes death and turns it inside out. Instead of the blood that gushed like wastewater into the drainage ditch in eighteenth-century Lyon, here blood is cast and preserved with infinite care (at minus-18 degrees Celsius). The execution here is not corporal, it is technical and art historical.

Made from eight pints of the artist’s own blood, Self is an auto-decapitation, an artwork that takes death and turns it inside out. Instead of the blood that gushed like wastewater into the drainage ditch in eighteenth-century Lyon, here blood is cast and preserved with infinite care (at minus-18 degrees Celsius). The execution here is not corporal, it is technical and art historical.

First created for the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1991, Quinn has made a new Self every five years. He has said that the series was inspired by Rembrandt’s self-portraits. “With Rembrandt, it’s really about him at every point and his personality, whereas mine is like a repetition of the same thing. It’s more of a twenty-first-century vision of progress.”

What does Quinn mean by that? In Rembrandt’s self portraits, the artist gazes back at us, his mirror. His eyes are open. In fact what is so astonishing about Rembrandt’s self-portraits is their penetrating and inquisitive gaze. The painter is scrutinizing himself without vanity. And it’s a human, flawed, and compelling vision as a result.

Self is the opposite. The eyes are closed, like a death mask, impenetrable. There is no spirit of the self here, as in Rembrandt. Here the presence is biochemical: plasma and DNA.

Maybe that is what Quinn, the son of a physicist, means by a twenty-first-century vision of progress: our contemporary Western impulse is to quantify, to understand the world as ones and zeros, and our humanity as a series of genetic codes.

Ironically, just as western European culture is reaching for a technological sublime in art and in science, with overtones of sci-fi cryonetics, the sinews of religion and history are simultaneously keeping us tied to the bloody origins of our humanity.