I loathe being a patient, but I am utterly fascinated with medicine as a lens for understanding contemporary society. So is Tod Lippy, editor of Esopus, the most recent issue of which is themed "Medicine.” With this issue, Lippy, who describes himself as “something of a hypochondriac,” has demonstrated a fundamental principle of pharmacy—that at the proper dosage, a substance otherwise poisonous can be palliative.

Wrapped in a matte image of rainbow-labeled medical charts (Lippy told me they are from his own doctors’ office), Medicine is a dossier of how humans (and Americans, in particular) metabolize health and illness.

The volume, which I didn’t put on the scale, but would guess is in the 90th percentile for weight, includes contributions from physicians, archivists, musicians, phlebotomists, and even interior designers. It passed its eye test with flying colors by including sumptuous reproductions of historical documents, ephemera, and original art. It’s audiological performance is pretty good too—pasted into the back cover is a CD of specially commissioned songs, each based on, wait for it, an “organ.”

But beyond the many visual and sonic puns that run throughout is a deeply serious investigation of the human condition. I teach history of medicine (which might have something to do with my ambivalent relationship to medical care). This includes helping medical students to think beyond biochemistry, to recognize that their therapeutic advice can also take the form of meditations on what it means to be alive and to die.

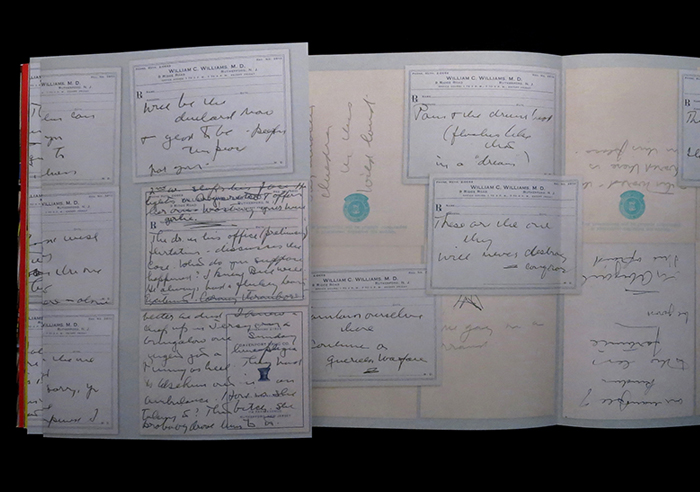

Until I opened this volume of Esopus I had not known that poems William Carlos Williams’ had written on his own prescription pads were in the archives of my own institution. Even though such materials will be harder to access while Yale’s Beinecke Rare Books Library and Archive is under construction over the next year, readers of Medicine can hold their own reproduction of a letter typed by Williams. In it, he explains that being a doctor will never be as important to his identity as being a writer.

Archival material © 2015 the estates of Paul H. Williams and William Eric Williams

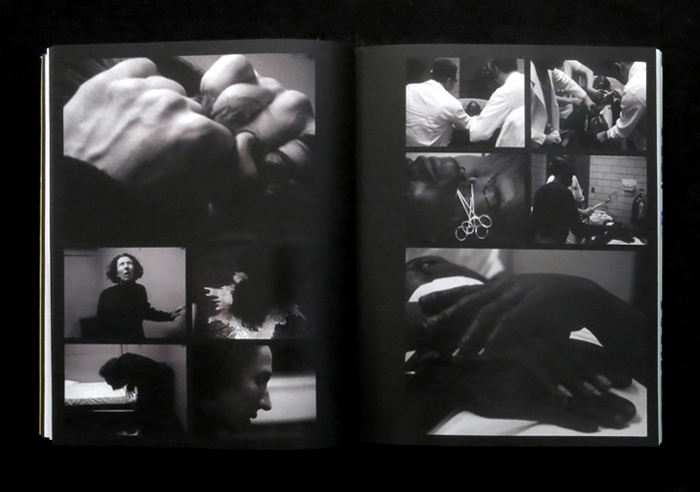

However, medicine is often less lyrical. Paul Austin, an ER doctor for over twenty years, provides the observation that “An emergency room can sometimes seem like the small end of a very large funnel of misery.” Here he presents slices of Frederick Wiseman’s cinema verite classic The Hospital. Stilling film into its component cells brings new life to scenes from a late 1960s New York City emergency room. One spread features a single frame of hands engaged in a surgical procedure, arranged such that they appear to be reaching in not only to the guts of the patient, but the gutter of the book itself.

©1969 Frederick Wiseman. All rights reserved.

In my teaching I emphasize that whether or not we are sick, medicine—and various processes of medicalization (birth, exercise, aging, addiction, and so forth)—infects the experience of being alive. And for this reason, I will be prescribing (er, assigning) Medicine.

http://www.esopus.org/