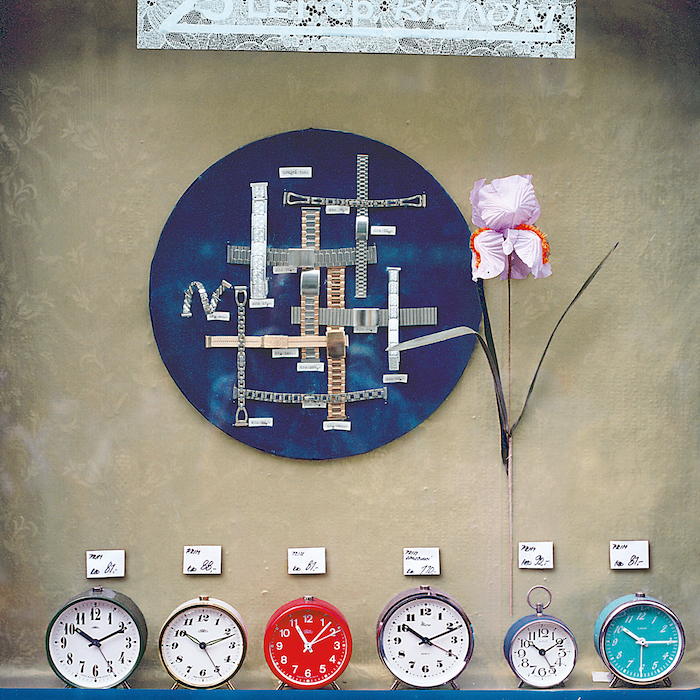

Moscow, 1990

The military shirts hang suspended, waiting for their invisible soldiers. Theatrical swathes of fabric; bombastic red stars; the surreal geometry of forms: it would be easy to mistake this display as a retro-cool art piece in an international Biennale. But it’s not. It’s a shop window in Moscow, circa 1990.

After the Berlin wall came down there was a year or two when a Westerner could travel to the former Soviet Bloc—Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia—and glimpse a prelapsarian age before shopping was Shopping, when products were simply products: no branding, no packaging, no targeted audience. The logos that adorn Western sneakers, shirts, and sunglasses were absent. Instead of the visual language of consumerism (luxury, sex, and the dream of personal reinvention) there were one-of-a-kind tableaux vivants of everyday things: lipstick, watches, soap.

Prague, 1988

I was in Budapest in 1990 and I remember well the shock of walking through those post-communist streets. Absent of homogenizing advertising, without franchises or chain stores, I felt a mixture of appreciation for the vernacular (look at that display, it’s just like a Malevich!), combined with the awareness that this was a privileged point of view: a form of aesthetic imperialism, if such a thing can be said to exist.

I was in Budapest in 1990 and I remember well the shock of walking through those post-communist streets. Absent of homogenizing advertising, without franchises or chain stores, I felt a mixture of appreciation for the vernacular (look at that display, it’s just like a Malevich!), combined with the awareness that this was a privileged point of view: a form of aesthetic imperialism, if such a thing can be said to exist.

Moscow, 1990

It was a time when communism was breaking up, literally dissolving on the street. Entrenched cynicism was giving way to gusts of liberation. An elderly man in a houndstooth jacket stopped me to talk passionately about the hardships of the communist years, the long lines and short supplies for essentials like meat, sugar, and bread. Whispered information, favoritism, and bribery could land you a coveted spot in the line at the front of these shop windows, but what you thought you were going to buy was not necessarily what you got (unless you went around the back).

It took the astute eye, the persistence, and the foresight of David Hlynsky to take 8,000 photographs of these shop windows, a heroic endeavor, both historically and artistically. A selection of these appear in the handsome new book Window Shopping Through the Iron Curtain.

Crakow, 1989

Crakow, 1989The images are simple and respectful; they are of a piece with the poignant austerity of their subject matter. They are also artful: cleverly framed, and hip to the play of reflections and angles.

Hlynsky caught that moment when the tectonic plates of the late twentieth century were shifting and the Cold War was ending. These windows, retrospectively picturesque, are the vestiges of a lost utopian ideology.

Yugoslavia, 1989

Window-Shopping Through the Iron Curtain by David Hlynsky is published by Thames & Hudson. This essay was originally published in June, 2015.

All images ©2015 David Hlynsky