The thing always happens that you really believe in; and the belief in a thing makes it happen.

—Frank Lloyd Wright

How many times can a man rise up from the ashes of his life—the murder of his wife, bankruptcy, imprisonment, savage attacks from the press—and still be able to design some of the most iconic buildings the world has ever seen? What makes a man persevere?

Frank Lloyd Wright always believed in himself, and it propelled his success, and it gave him unshakable confidence in the face of tragedies that would have broken a lesser man. But that supreme self-confidence also drove him to abandon his wife and six children, flaunt the law, and spend his money recklessly on rare Japanese art, custom cars, and handmade clothes. He was a man driven by his own genius, prone to excess, and haunted by his childhood.

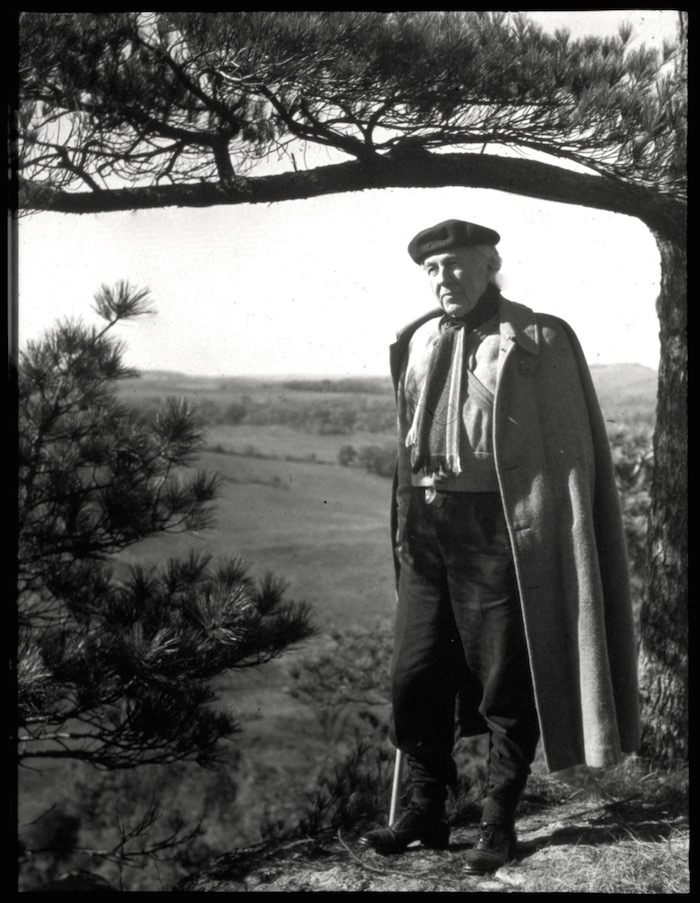

Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin | photo: Ken Hedrich

Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin | photo: Ken HedrichAt the age of sixty-eight, after enduring twenty years of near penury, he staged a triumphant comeback that lasted until he was ninety-two and climaxed in a visionary building that stunned the world.

Wright was a self-mythologizer, the architect of own his own story, a man who invented his image (flowing cape, dramatic hat, superfluous walking cane) as skillfully as he drafted his buildings. He anticipated the cult of the celebrity artist. You can see this in the pages of his autobiography, and in his interview with Mike Wallace, conducted just at the end of his life. As playwright Arthur Miller said of him, “he was a great romantic, a man of style … who Orson Welles would love to have played.”

There are defining moments in everybody’s life, where the road forks and everything changes. Wright had a number of dramatic turns but the one that scarred him the deepest was the murder of his greatest love, Mamah Cheney, the woman he had left his wife and children for.

Mamah and Wright fled public scandal by running away to Europe for two years, but on their return to America Wright built a stunning house for her—Taliesin—on the land where he had grown up, and where, as a child, he had been enchanted by the beauty of nature (the imprint of those summers would be the inspiration for his visionary ideas of organic architecture). But the idyll of Taliesin was forever destroyed the night Mamah was murdered by an ax-welding cook, and the house set on fire.

Frank Lloyd Wright home and studio, studio view, Oak Park, Illinois | photo: Jon Milller Hedrich Blessing

He was determined to rebuild, and he did. This was the place where he would later experience crushing financial pressure and two more devastating fires. But he always rebuilt, just as he did his life. His career would take him to Germany, Italy, Japan, England, and New York, but he would always think of Taliesin as his home.

Wright was deeply traumatized by his catastrophic losses, and suffered from a kind of PTSD of the soul, but when it came to his work, he was supremely confident, even arrogant. When a client once complained of water leaking from the roof onto his desk, Wright said, “well, move your desk.” His belief in his own genius was unyielding. It was rooted in the fierce encouragement provided by his mother, starting from when he was a child, when she hung architectural prints of English cathedrals in his boyhood room.

At the end of his life was another formidable woman: Oglivanna (as she was known). She steered him through bankruptcy and near homelessness, when Taliesin was foreclosed on. And it was she who conceived the brilliant idea of forming a kind of work camp for aspiring architects, a place that would provide financial stability, and enable his extraordinary creative comeback. It was also a place where apprentices could rub shoulders with the Master. The Master who once, pressured by a client who had waited for almost a year to see the plans for his house, sat down at his drafting table and in one extraordinary creative burst designed, in three hours, Fallingwater, one of the most stunning houses ever conceived.

He was a flawed, complicated, self-deluding, but supremely gifted man. If Frank Lloyd Wright hadn’t existed, you couldn’t have made him up.

Fallingwater | photo: Bill Hedrich

Adam Harrison Levy is collaborating with Susan Josephson on a film treatment of Frank Lloyd Wright's life.