This week, I attended one of the best exhibitions on graphic design I’ve seen in many years, at the Chicago Cultural Center. On display was the fascinating story of Valmor Products, an African American skin and hair care enterprise infused with good luck messaging, Hoodoo, and the incredible and influential graphics of two African American designers, Charles C. Dawson (1889–1983) and Jay Jackson (1905–1954).

The story of Valmor Products runs deep into African American culture, where in the 1920s and 30s, many African Americans used Valmor skin-lightening creams and other products advertised in the backs of magazines and in black neighborhood stores. It was illustrator and designer Charles Dawson who was the originator of Valmor’s signature human faces that were drawn in a flat linear style and portrayed jet black hair streaked with reflective patches of white. According to the exhibition, Dawson was a strong advocate of black heritage and pride, striving to create “pleasing Negro types” without exaggerating racial features. His figures suggested a mixed-race identity that also reflected that that the products were also intended for sale to other ethnic groups. The products at Valmor were targeted to African American women who wanted light skin, and though living in the North, still held on to remembered or passed down superstitious beliefs of luck and talismans from the South.

It is interesting to note that Valmor products was founded by Morton and Rose Neumann, a Jewish couple who ran the business until it closed in the mid-1980s. They employed not only African American graphic designers but sales people as well. Neumann was born in Chicago, worked for a time in New York, and eventually moved back to his hometown where he started Valmor. He sold his products under at least two names, the Valmor brand and the Madam Jones Co., though which he sold spiritual supplies, incense, talismanic oils, and other occult products.

Almost all of the Valmor products had highly sexualized illustrations and texts (like their product “Essense of Bend-Over”). Many products implied that hair treatments of pomades and oils would help men—and especially women—prevail in affairs of the heart.

Valmor advertising imagery was appropriated, then altered, by the Rolling Stones in their top-selling album Some Girls, which was designed by Peter Corriston, a top album designer of the time. Valmor also influenced the cartoonist R. Crumb, who kept Valmor products and packaging as part of his reference inspiration. As for mainstream artists, Claes Oldenburg included a Valmour catalog in his famous Mouse Museum, an exhibition of popular culture in the 1960s and ’70s. Chicago Imagist Roger Brown had Valmor incense cans at his studio and Christina Ramberg made paintings reflective of the Valmor style.

There is a book waiting to be written about the entire Valmor story. The story is packed with direct connections to African American popular culture from the 1920s to 1980s, to Hoodoo and conjure practitioners, advertising, design, typography, underground comics, and modern art.

Would we want anything else?

Installation view of “Love for Sale: The Graphic Art of Valmor Products” at the Chicago Cultural Center

Valmor ad for perfumes, c. 1930s

Example of the highly graphic cartooned style of designer and illustrator Charles C. Dawson (1889–1983).

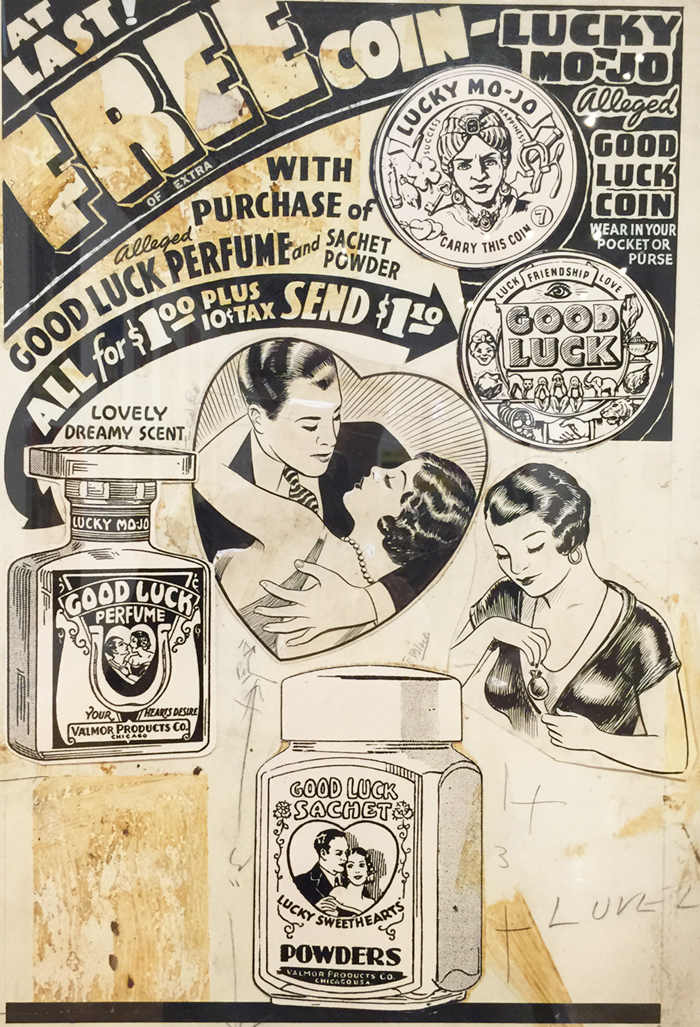

Original paste up for advertising, exhibiting good luck coins and perfume. Art by Charles Dawson.

Installation view

An example of the sexually explicit advertising of the Valmor line.

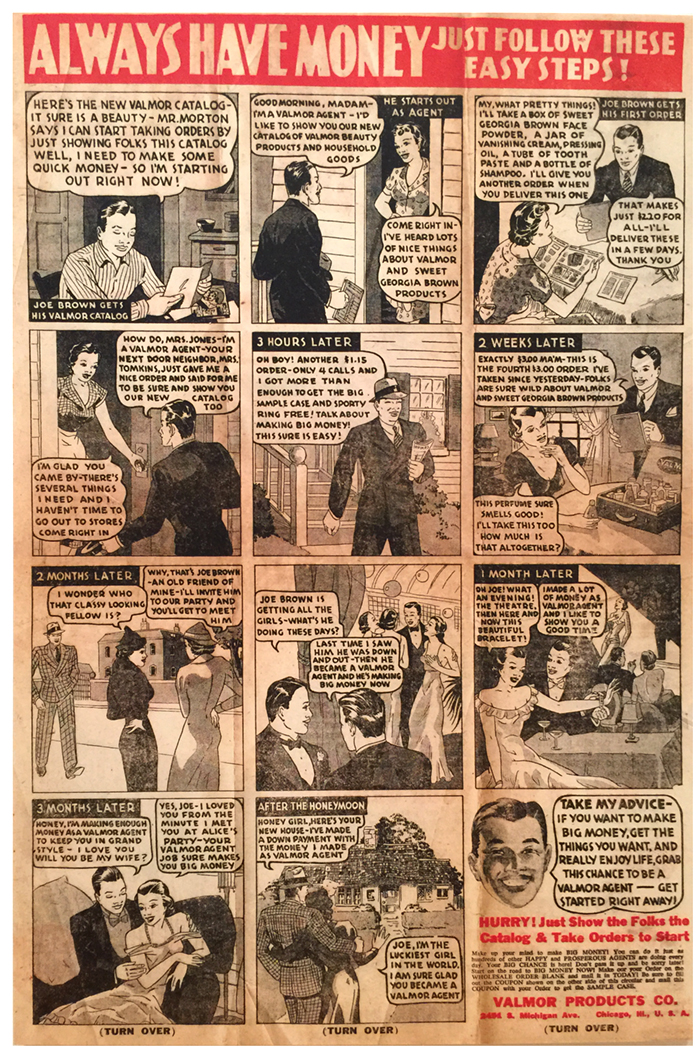

Graphic display of a Valmopr label for Mojo Brand Oil. Advertising page of cartoon illustrating how one could get rich selling Valmor products. Art by Jay Jackson.

Advertising page of cartoon illustrating how one could get rich selling Valmor products. Art by Jay Jackson.

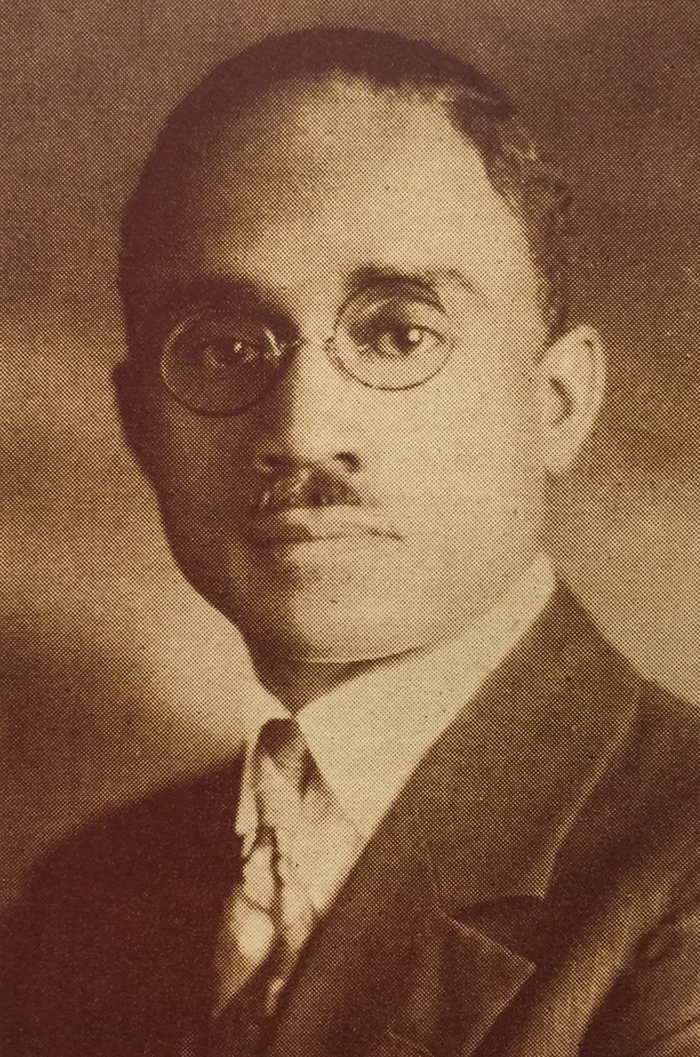

Charles C. Dawson (1889–1983)

Jay Jackson (1905-1954)

Label for Lucky Brown Brighten Cream. Art by Jay Jackson.

Label for Sweet Georgia Brown Lemon Fragrance Lotion. Art by Jay Jackson.

Advertising for Jickey Sweet Perfume, with the phrase “put on your jickey every day.”

Viewers photograph the Rolling Stones album cover, which was created by Peter Corriston by appropriating original art from Valmor.

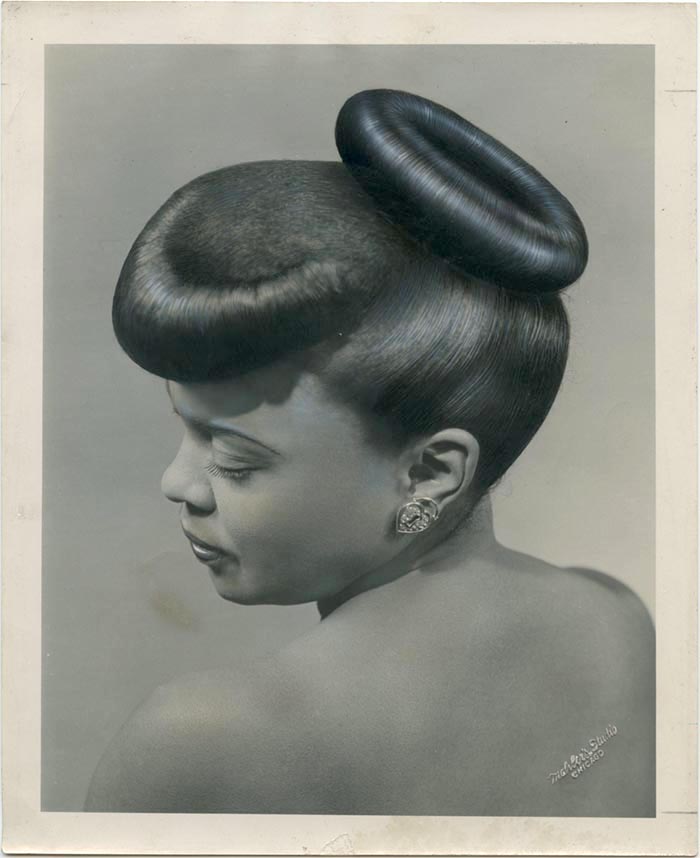

The display included examples of models used by Valmor for product advertising.

An original, highly retouched gelatin silver print used by Valmor in product advertising. Collection of John Foster.

All photographs by John Foster