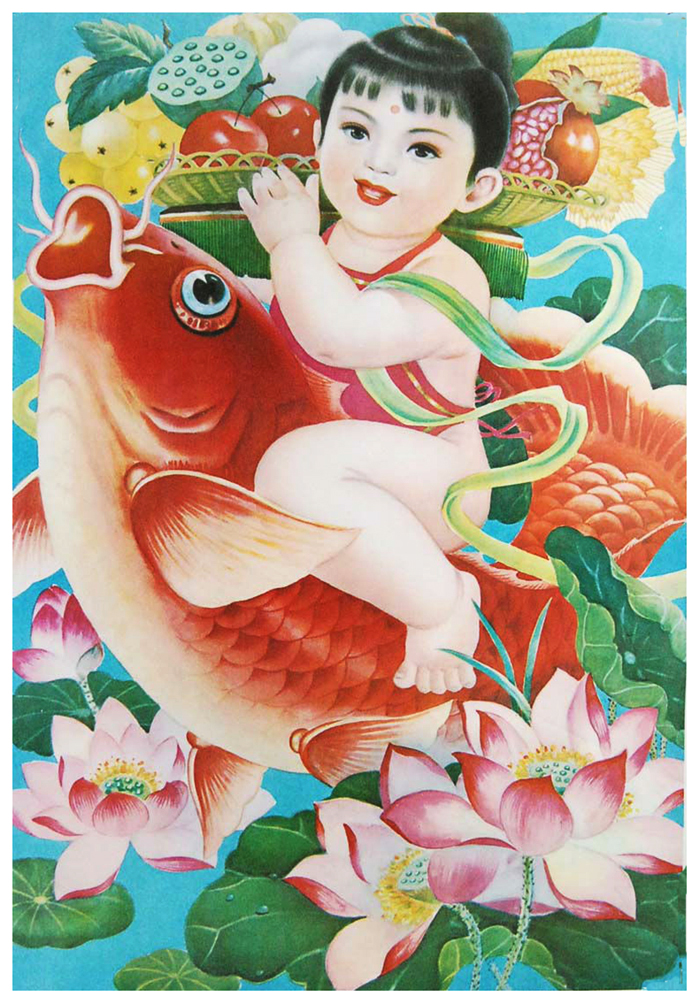

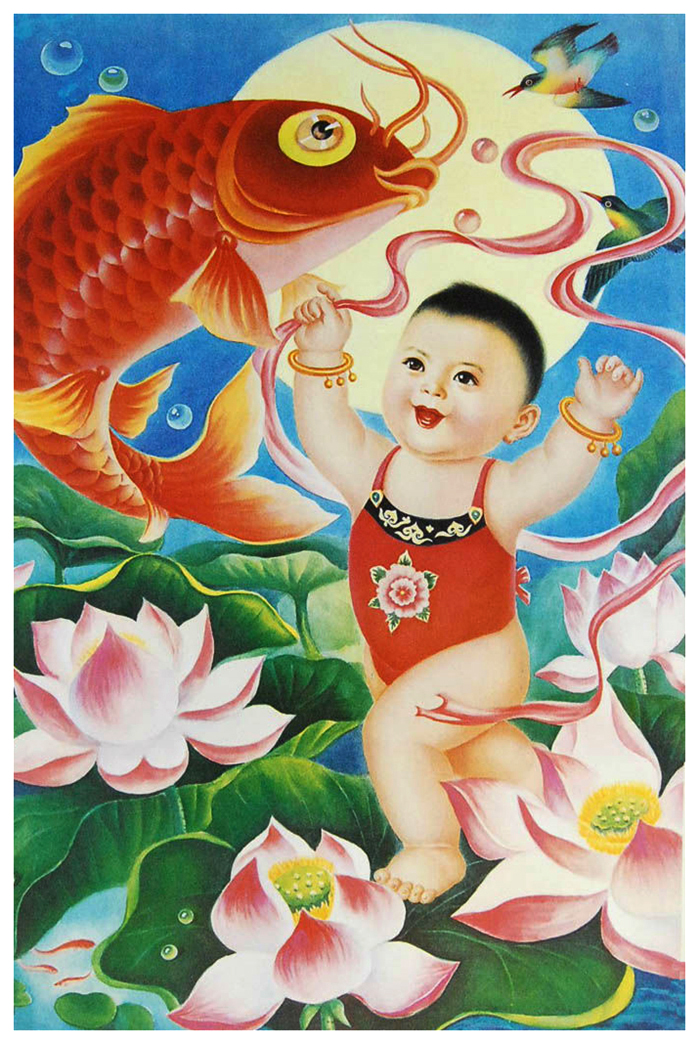

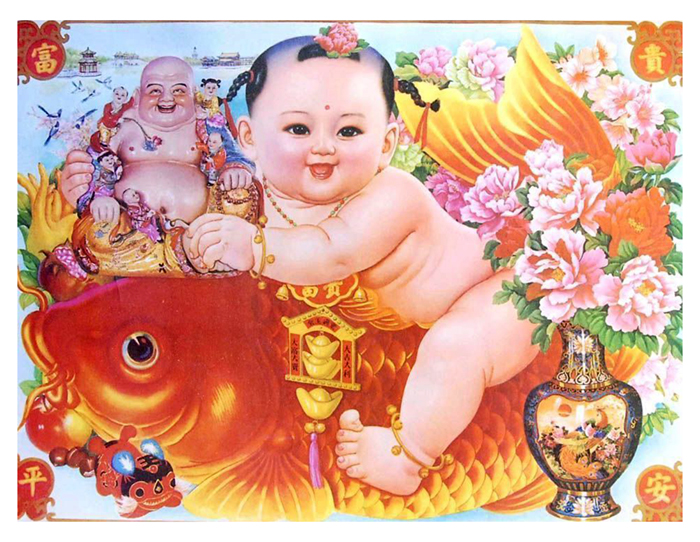

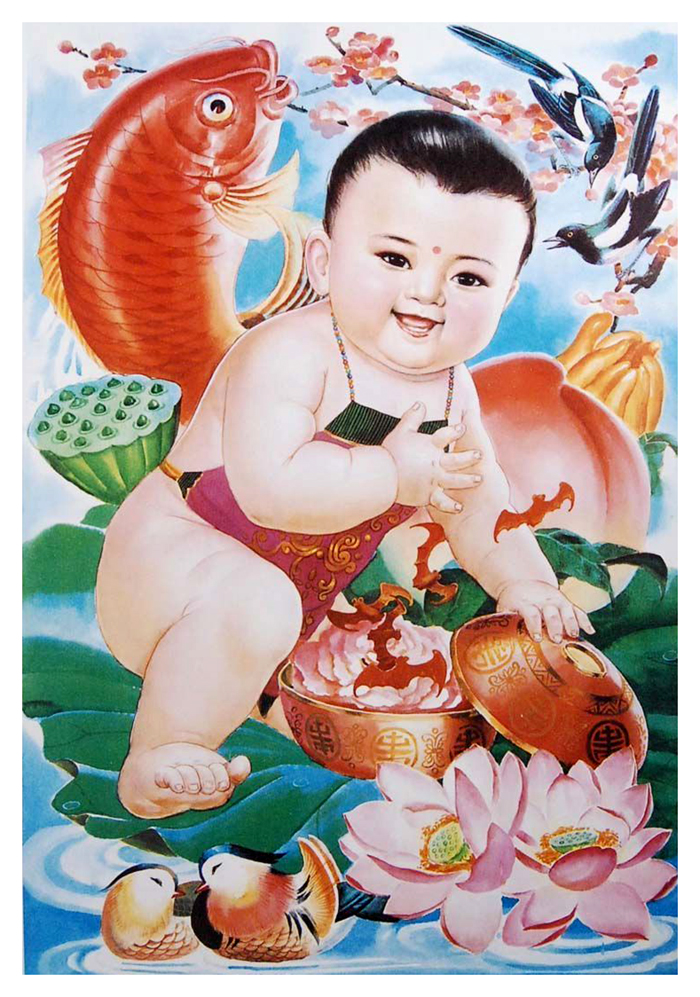

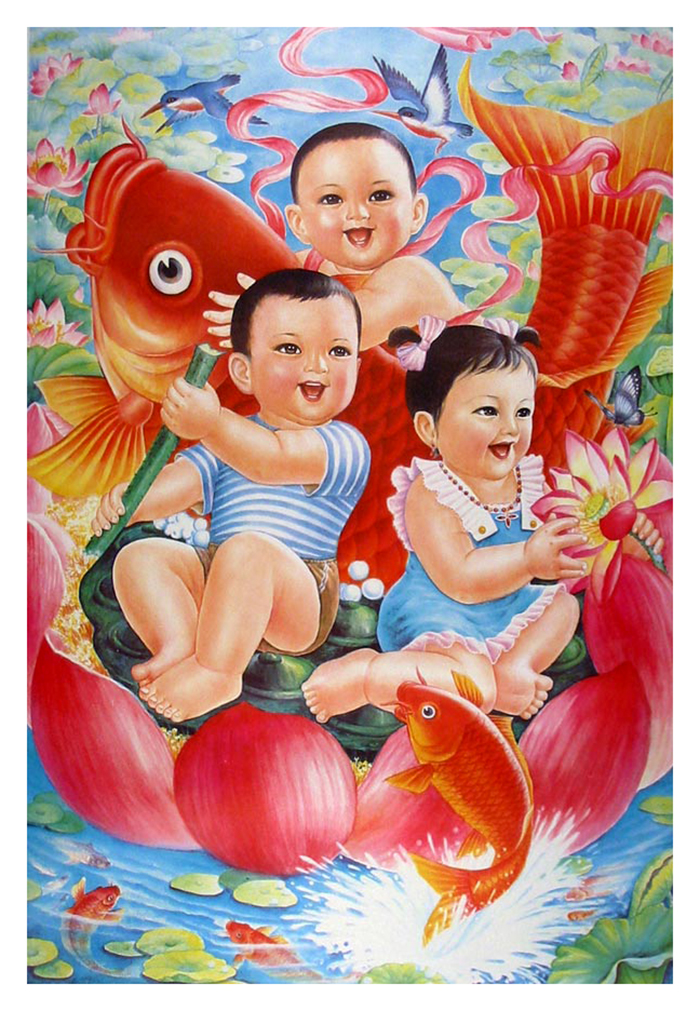

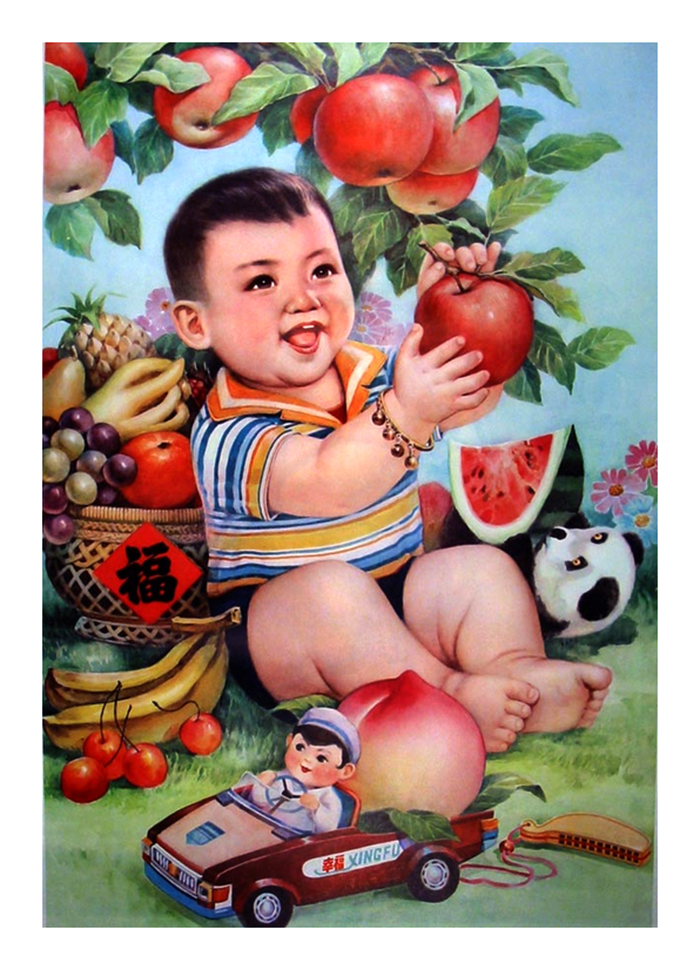

During the late 1970s and ’80s, China was awash in New Year prosperity posters of chubby, rosy-cheeked babies, many astride or cavorting with huge goldfish.

Whimsical and kitschy to Western eyes, the aim of these posters was to wish health, fortune, and good luck for the coming year. Pumped out by artisans and designers working for the Chinese Communist Party, these posters were printed by the millions and distributed free in the country’s rural outposts during the New Year Festival. One account reported that as many as twenty different versions of the posters would appear in some provinces in the same week. Other versions appeared on calendars, all meant to perpetuate the notion that all was well across the country.

The posters were well-liked and enjoyed for the good cheer they brought to the lives of hard-working farmers and rural villagers. Another contingent, pregnant mothers, enjoyed seeing images of fat, healthy babies, hoping good luck would come to their own offspring. Goldfish have long been a symbol of bounty and surplus in China, so putting one or two of these with fat babies was natural. Other symbols, like the peony flower, assured noble status and wealth.

Vintage posters like these are highly collectible today, though reproductions are easily had.

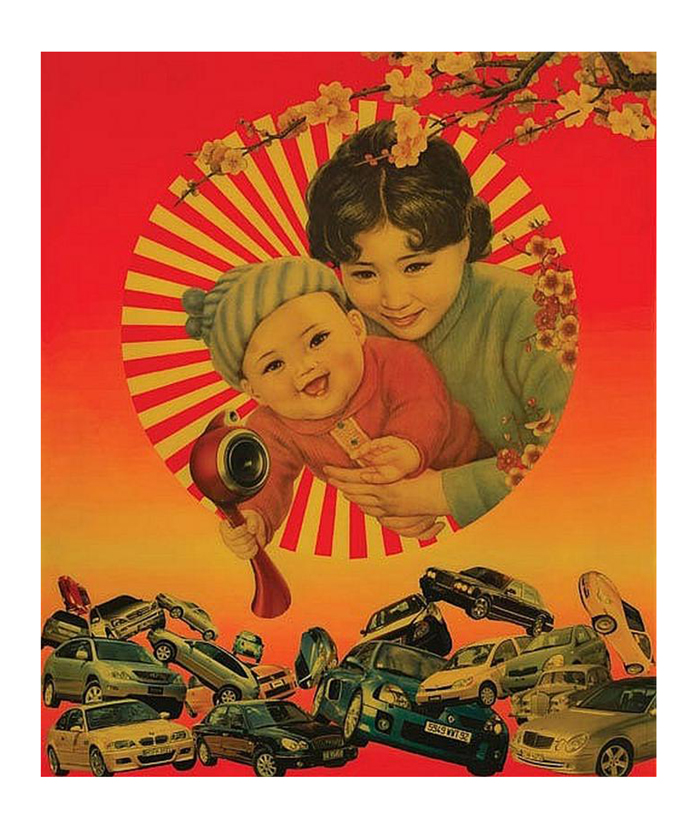

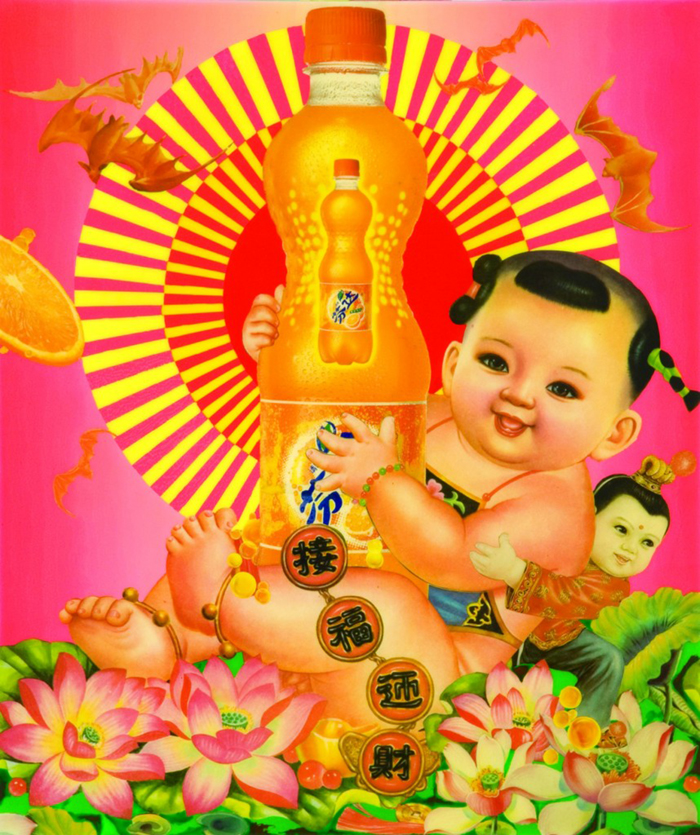

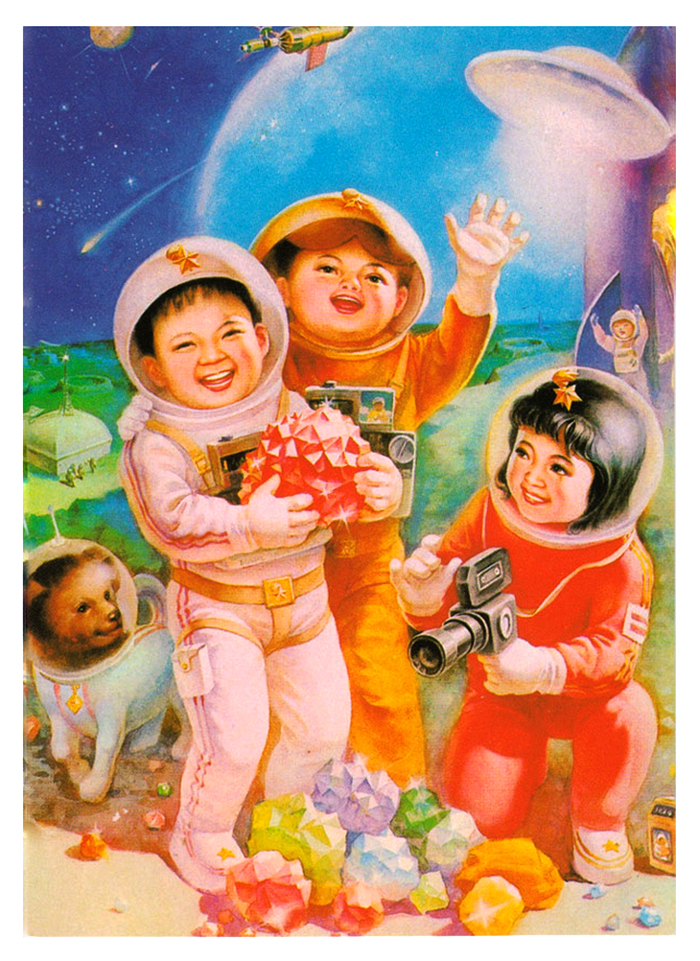

In a creative response to the propaganda machine of old China, three Chinese artists known as the LUO Brothers—Luo Wei Dong (b. 1963), Luo Wei Guo (b. 1964), Luo Wei Bing (b. 1972)—make art that parodies the propaganda posters of the 1980s. For the last fifteen years, the brothers’ art has been a mash-up of this traditional Chinese poster with garish examples of Western consumerism—things like televisions, mobile phones, chewing gum, and brands like Coca-Cola and McDonald’s. The LUO Brothers imagery echoes the pop art movement in the United States more than a half-century ago, but it is nonetheless relevant.

Luo Brothers | Double Happiness (The World's Most Famous Brands Series), 2008 | © LUO Brothers

Luo Brothers | Untitled, 2009 | © LUO Brothers

Below: Luo Brothers from The World's Most Famous Brands Series