Few crimes are as unassumingly designed as hacking. Banal knots of computerized code can bring giants like Target, Google, Apple, or Sony to a standstill, seizing their intimate data: credit card and banking numbers, damning emails and pictures, classified corporate strategies. To protect themselves, corporations have long sought to understand who hackers are and how they design their assaults.

AT&T was one of the earliest tech firms to lead the charge. In 1969, they compiled a pioneering “stereotype” of hackers and the “burglarious” tools they used to loot $4 million annually from pay telephones, at the time the most widespread, valuable technological system in operation. In Coin Telephone Larcenies, a confidential brochure printed to aid police, AT&T precisely illustrated how high tech crime was conducted. The publication is utterly unique. An official guide to a subterranean world, it offers a pre-digital chronicle of hacking, when perpetrators trafficked in lock-picks rather than lines of code.

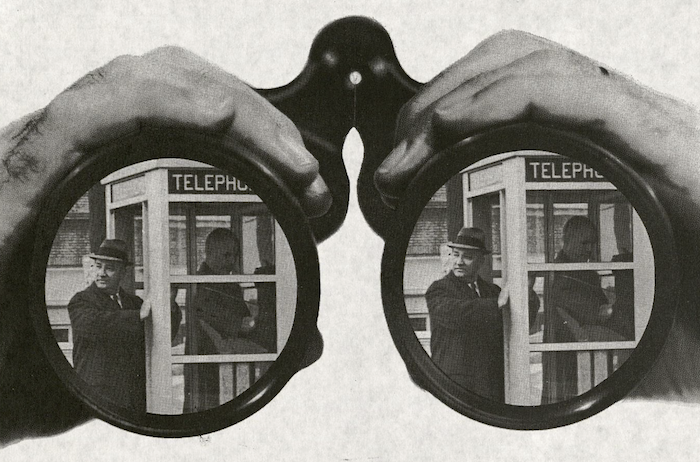

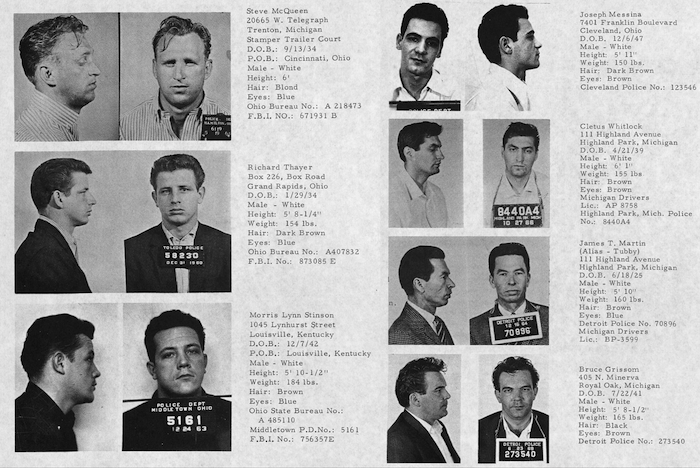

AT&T’s brochure resembles pure pulp fiction. The company portrayed phone hackers as fedora-wearing thugs, lurking in motels, roving from city to city. Although only one in forty-five hackers were apprehended on average, and only one in sixty were ultimately convicted, AT&T was determined to put faces to these crimes. Coin Telephone Larcenies is filled with mug shots. Ranging from twenty-seven to fifty-two years of age, these prehistoric hackers sport pompadours, trailer park addresses, and memorable names such as Cletus Whitlock, Raymond Lee Rust, and Steve McQueen. In selecting these suspects, AT&T framed hackers as a misguided fringe element, a characterization that persists into the present.

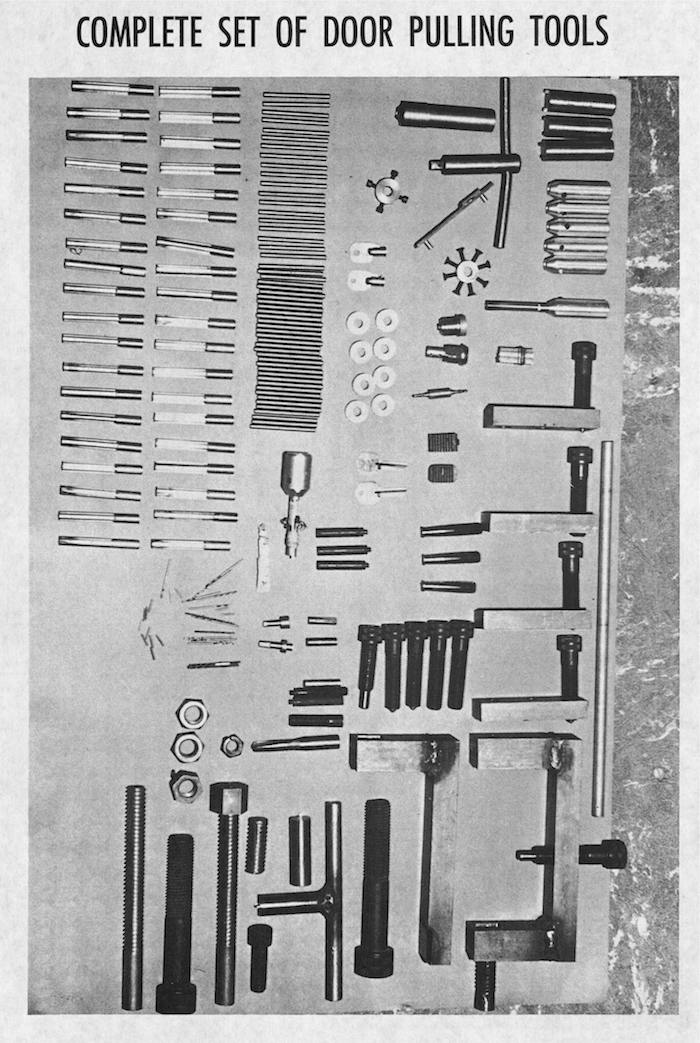

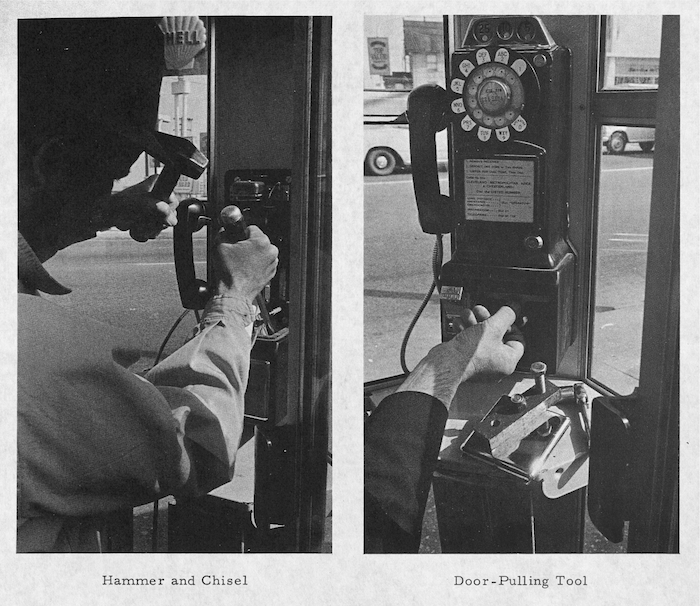

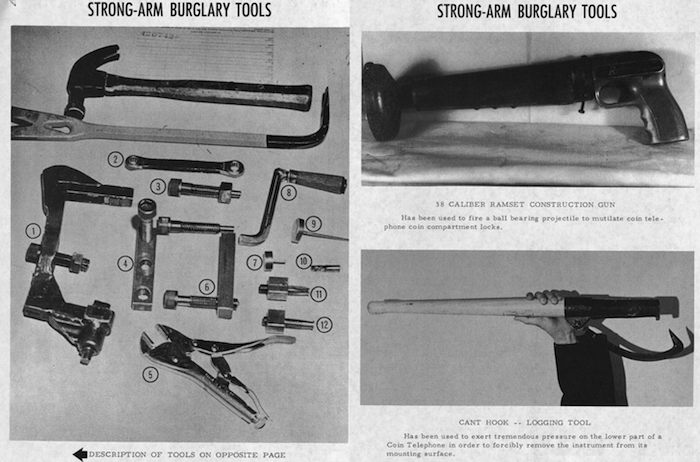

AT&T divided hackers into two camps based upon how they designed their instruments. The first group, composed of “sophisticated” lock-pickers, employed plugs and vises, hammers and grinders—even spare steak knives. In two minutes flat, these humdrum “door-pulling tools” could pop open a pay phone’s cash box without damage. Lock-pickers ranked first on AT&T’s most wanted list since their hacking often went undetected, allowing for an effortless getaway or repeated robberies. A lock-picker’s penchant for wearing an “attractive looking suit,” carrying an attaché case, and “leaving the scene in a nice looking car” abetted their slippery nature.

.png)

By contrast, lock-pickers’ brutish brethren the “strong-arms” were easily spotted. Wielding crowbars and logging hooks, these hackers ripped pay phones from their fixtures and carted them off, prying into their cash boxes later in the backseat of a car or a motel room. If this required too much patience, strong-arms opted for “shoot outs,” punching phones open with ball-bearing-loaded construction guns. Given their outrageous methods, strong-arms had a much greater chance of being caught.

Despite identifying hackers in the Coin Telephone Larcenies brochure, and detailing how they designed their heists, AT&T admitted that these criminals would remain elusive. Like contemporary hacking groups such as Anonymous, most hackers in the 1960s worked inconspicuously as they ransacked a vastly dispersed technological system. Even with advanced knowledge of lock-pickers and strong-arms, policing every pay phone would prove impossible. Only innovations in design, AT&T opined, might deter hackers and staunch the millions they plundered each year.

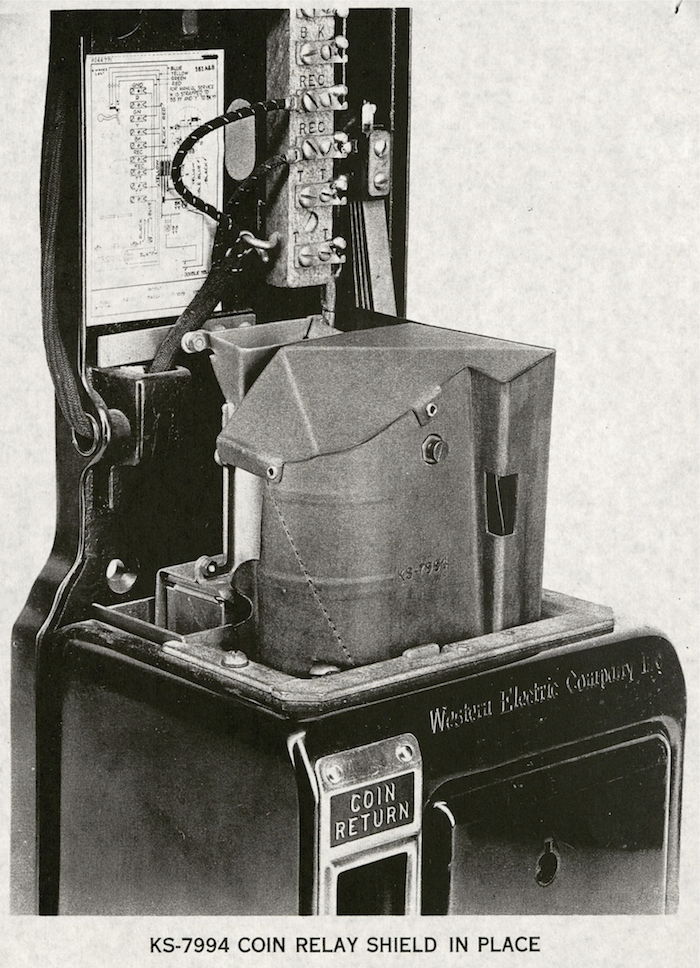

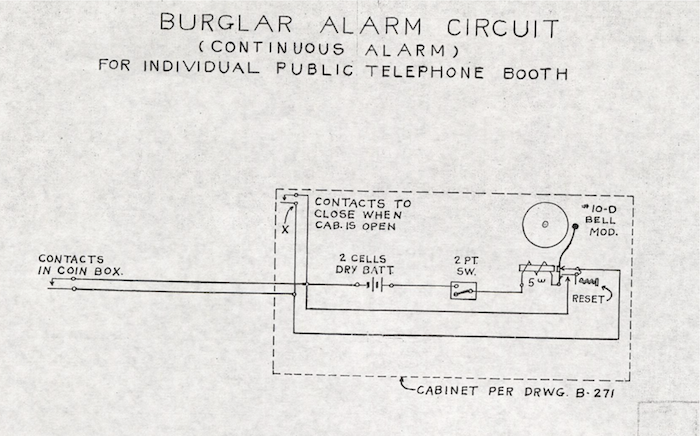

As the 1960s ended, AT&T launched an array of veiled defensive strategies, matching the invisibility of hackers. First, the company’s design team at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey, forged “coin relay shields.” These galvanized sleeves of protection hidden within cash boxes could withstand gunfire at close range. Seeking ever more imperceptible types of security, AT&T engineered a “talking pay phone” outfitted with a silent alarm. Hidden in the phone’s cash box, this miniature sentry sent electronic alerts to AT&T personnel at even the slightest provocation from a lock-picker.

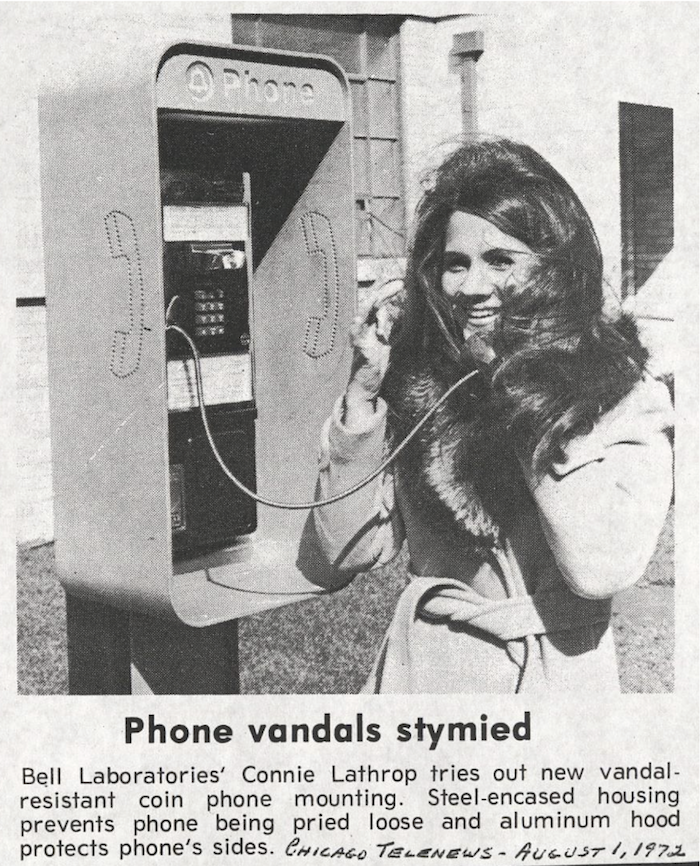

At their shrewdest, AT&T’s designers crafted aluminum hoods for pay phones. The rugged housings were a simple, ingenious way to prevent strong-arms from peeling pay phones off their fixtures with crowbars. Yet the design did not announce itself as a security measure. Rather than bring unnecessary attention to criminal activity, AT&T’s designers hoped most customers would think the hood was a form of weatherization, shielding pay phones from snow, rain, and harsh sunlight.

Downplaying its real purpose, the aluminum hood succinctly captures the tenor of hacking culture. Despite occasional high-profile news coverage, hacking remains a cloak-and-dagger affair, in which monolithic organizations wage a concealed, complex war against unseen assailants—a contest of design thrumming far beneath the surface of everyday technologies.