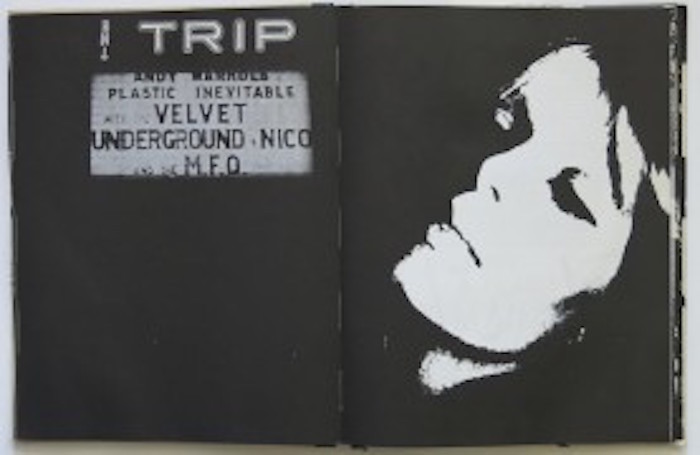

It’s been called a pop-up book for hipsters, but Andy Warhol’s Index (book) is much more than that: it’s an artist’s book that turns the very concept of an artist’s book inside out with glamorous insouciance. It’s a product of Warhol’s Factory—industrial rather than hand crafted, a commercial collaboration rather than a work of an individual artist. The high-contrast black-and-white photographs of Edie Sedgwick, Lou Reed, John Cale, and Nico exude seductive splendor. The typography is proto-punk.

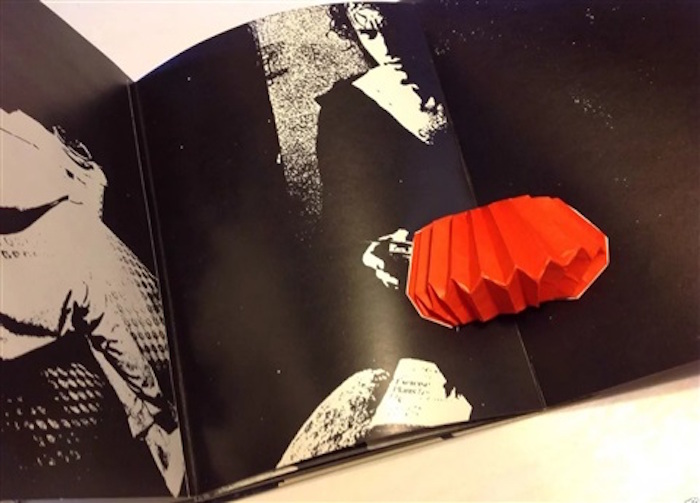

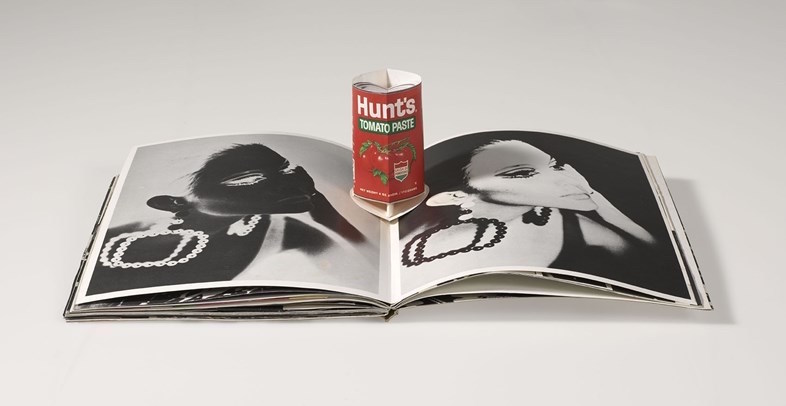

Additional features elevate the book into the realm of experiential art: paper pop-ups of a can of Hunt’s tomato paste, a castle, a bi-plane, and a red accordion that squeezes out a note when you turn the page. Also included, like treats in a box of Cracker Jacks, is a silver balloon and a set of stamps with Warhol’s signature (if you dip the panels into water his autograph disappears). But the ultimate insert is a flexi-disc LP that is an audio meta-textural moment: Nico, Lou Reed, and John Cale discussing a mock-up of the book itself (three dummies were produced until a final version was agreed upon). A Velvet Underground track plays in the background. The book is a multi-dimensional and a multi-sensory experience.

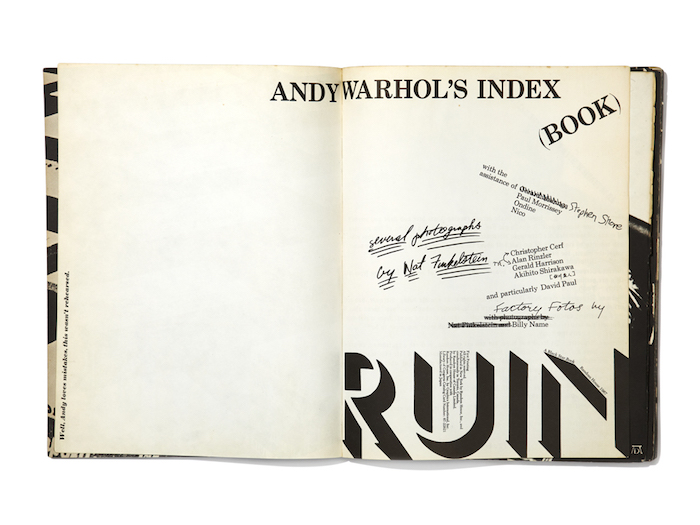

The book is radically innovative in another way: it takes the standard artist interview and subverts it with insouciance. Billy Name, who was in charge of the book’s production (Alan Rinzler brought the idea to Christopher Cerf at Random House, David Paul was the designer and Graphics International manufactured the pop-ups), had originally conceived of it as a literal index of Warhol’s films. But when Random House demanded actual text, Billy Name hunted through the files at the Factory for interviews that would satisfy the requirements.

He chose interviews that were “like Warhol Factory stuff (as opposed to New York Times or Art in America stuff).” These are interviews that through Warhol’s evasiveness and cunning undermine expectations of the artist interview. They are in stark contrast to the interviews of the previous generation of artists, the Abstract Expressionists: the profundities of Mark Rothko (“The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them”) or the sincerity of Jackson Pollack (“Something in me knows where I’m going, and—well, painting is a state of being. … painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is”).

Instead, in an interview by Joseph Freeman, which is printed in the book, you get this:

“Do you think pop art is…”

“no.”

“what?”

“no”

“do you think pop art is…”

“no … no I don’t.”

“why did you leave commercial art?”

“uuuhh, because I was making too much money at it.”

“Is your present work more satisfying?”

“uuuh, no.”

It’s easy to dismiss Warhol as being silly here, just as people in the art world initially dismissed the Campbell's soup cans as being trivial. But in the same way that Warhol distorted the shiny banality of advertising imagery (see the smudgy graininess of a Campbell's soup can silkscreen) he was also subverting the conventions of artist interviews.

In fact, in 1966 he upended a televised interview with the art critic Alan Solomon in a comically deadpan way. Perched on a director’s stool in front of an enormous silkscreen of Elvis, dressed in his characteristic black leather jacket and dark shades, Warhol at first shakily evades the condescending questions but gains confidence when he slyly suggests that Solomon tell him the words he wants to hear and he’ll just repeat the answers. Solomon interprets this as insecurity and offers to guide him through the interview. Warhol turns the tables on him. “You just tell me the words and they’ll come out of my mouth.” Solomon swivels back and forth in his chair uncomfortably. “Let me ask you some questions and you can answer,” he says patronizingly. “Oh no,” Warhol says gaining more control, “you repeat the answers, too.” “But I don’t know the answers!” replies Solomon, with hint of panic in his voice. He tries to look nonchalant but it’s too late: his authority has been stripped away.

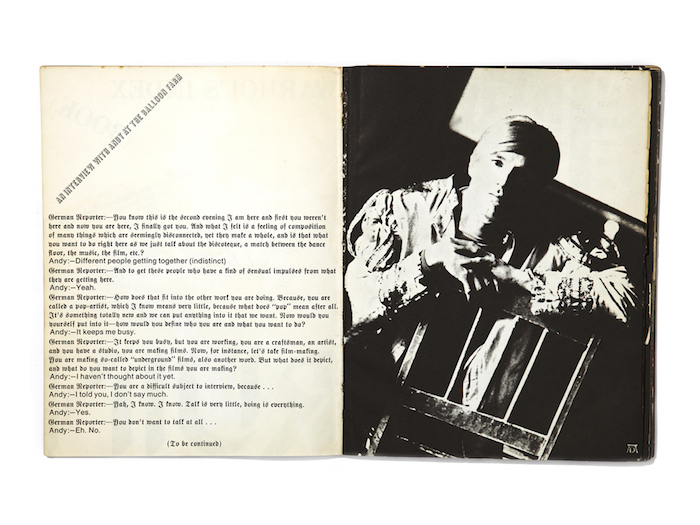

A meaningful interview is a form of collaboration. Gay Talese, a writer known for his meticulous in-depth reporting, has described how he becomes “a partner in their own understanding of themselves” with his interviewees. Warhol actively resists such psychological probing. In another interview in The Index (book), a German journalist poses the type of earnest semi-academic questions you could imagine a critic from Art in America asking. When he asks a convoluted question about how Warhol defines himself as a Pop artist he gets this reply: “It keeps me busy.” Warhol evades self-revelation as effectively as his commercial imagery evaded the language of painterly representation.

Warhol could also be flirty, which is another diverting tactic. Back to the Freeman interview:

“What color are your eyes?” asks Warhol.

“I think they are blue but my mother says they change a lot.”

“They look … they look brown.”

“Yeah that’s what she says. She says at night they look brown.”

“Well, why did you say they were blue?”

“Because that’s the color I’ve known all my life. She says they’re blue.”

“Really?”

“Yeah, they’re blue”

“They’re brown.”

“They’re blue.”

“They’re brown.”

“Yeah, I mean, you know, it’s not my fault. I just thought they were blue.”

Warhol was distrustful of interviewers because he was wise to their ways. He understood how the form, seemingly true-to-life, was in reality a fictional construct that could be edited to suit the interviewer’s ends. “I’ve found that almost all interviews are preordained,” he says in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (which was not written but spoken into a tape recorder), “They know what they want to write about you and they know what they think about you before they even talk to you.” Warhol used sly humor and seeming naiveté to skillfully evade and confuse. He would even purposefully give out different autobiographical information to various outlets and watch with amusement as it circulated through the media landscape. He took delight in figuring out what newspapers and magazines a person read by what they repeated back to him. “It was like putting a tracer on where people get their information.”

In a 1963 interview Warhol had famously said, “I think everybody should be a machine.” But he was no machine when it came to being interviewed, quite the opposite. He was a cunning manipulator of the form, playing with it as self-consciously as he did other aspects of popular culture. A few years after Index (book) was published, he would take the reigns into his own hands by publishing a new magazine, Interview.

Warhol By the Book is up at the Morgan Museum & Library until May 15