The first quarter of the century in Europe abounded with “-ism’s”—art movements like Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Orphism, Constructivism, Suprematism, Dadaism, Surrealism, and others. The amount of artistic and cultural change happening there was dizzying, and the Western world watched in awe. It would be mid-century before the United States caused focus to shift to New York as the center of the avant-garde.

But before New York grabbed the headlines, one of these movements—Futurism (1909–29), blossomed first in Italy and pushed the extremes of creative innovation and experimentation. Though it focused on new ideas and technologies through the arts, this avant-garde movement was so strange as to border on the insane. Its manifesto celebrated speed, machinery, violence, youth, industry—and advocated for Italian modernization.

For example, this line from their manifesto: “We affirm that the beauty of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car with a hood that glistens with large pipes resembling a serpent with explosive breath… a roaring automobile that seems to ride on grapeshot — that is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

As with many of these cultural shifts, the movement was a jolt to the landscape of the artistic status quo.

Russian Cubo-Futurism (1913–15) owed much to the Italian movement, and but blended the exciting art style of the Cubists. Cubo-Futurism combined the newly emerging fractured Cubist work with the Italian’s dynamism of speed and modernization. This subset manifested itself in the fine arts with artists like Natalie Goncharova and Kazimir Malevich, but it was also prominent in graphic design—especially with the tradition of small, handmade books. For typographers, the vogue was asymmetrical type, white space, varying column widths, weight variations—even handwritten pages and tipped in artwork. For designers of books and printed materials, it was a revolution that voided most design rules, as you will see in the examples below. Cubo-Futurism (and others) gave rise to a new generation of typographers, especially Jan Tschichiold (1902–1972), whose book The New Typography, initially published in 1928, led to his being a leading advocate of Modernist design principles.

These book covers and inside spreads were found on the website Digital Library GPIB Russia. The open digital library contains a collection of documents and materials on national and world history. It contains books on genealogy and heraldry, history, military affairs, the sources on the history, ethnography and geography of Russia. It is sponsored by the State Public Historical Library of Russia.

++++

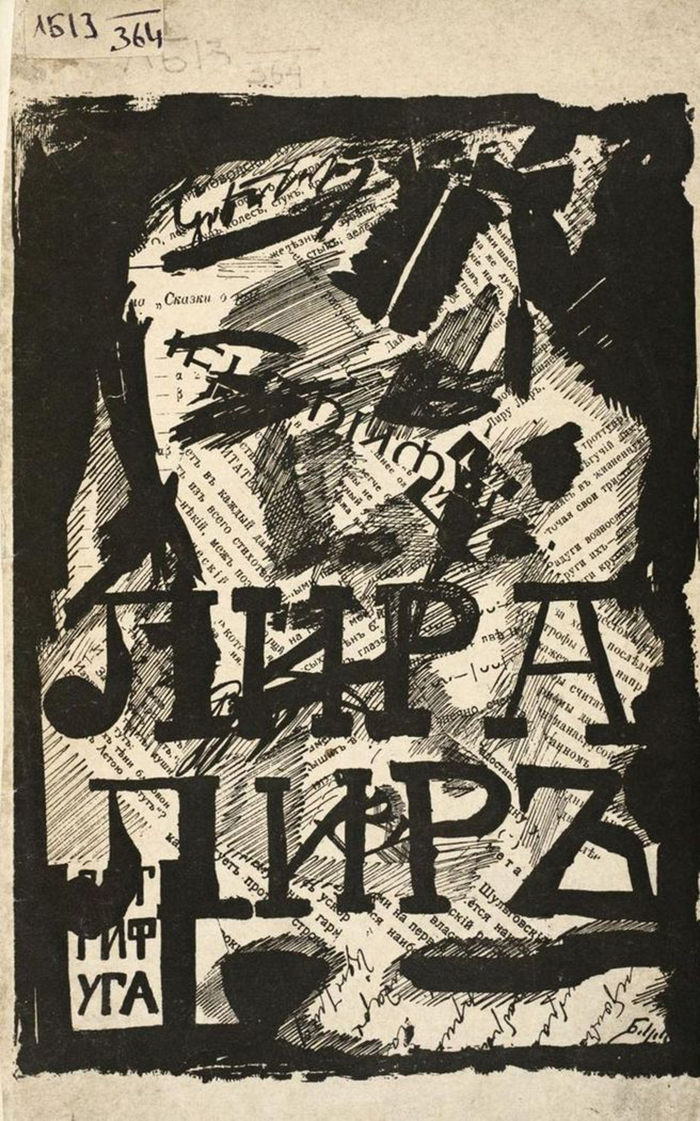

Sergei Pavlovich Bobrov (1889–1971), Lira Lira: The Third Book of Poems

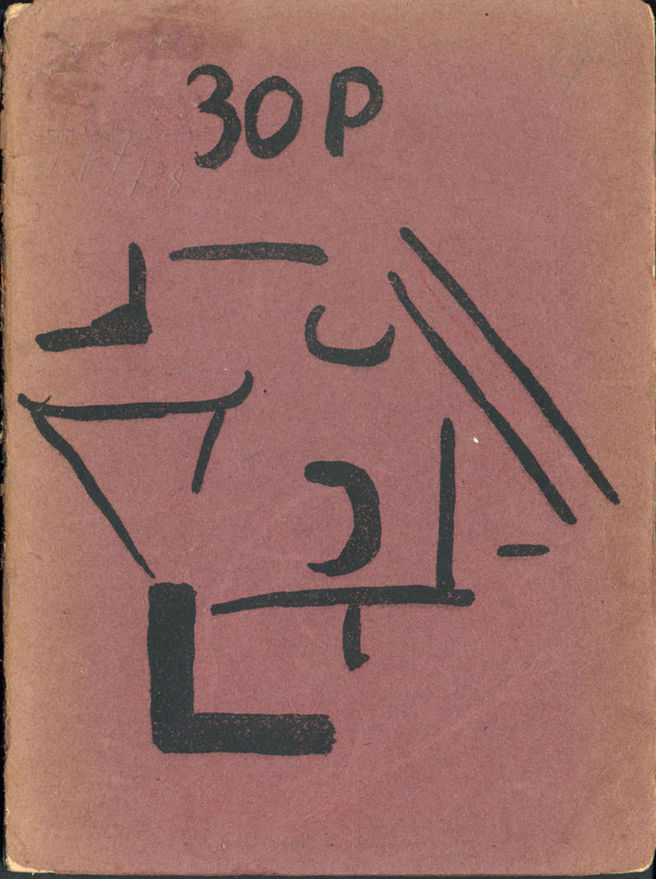

Nikolai Aseev (1889–1963), CDR

Nikolai Aseev (1889–1963), CDR

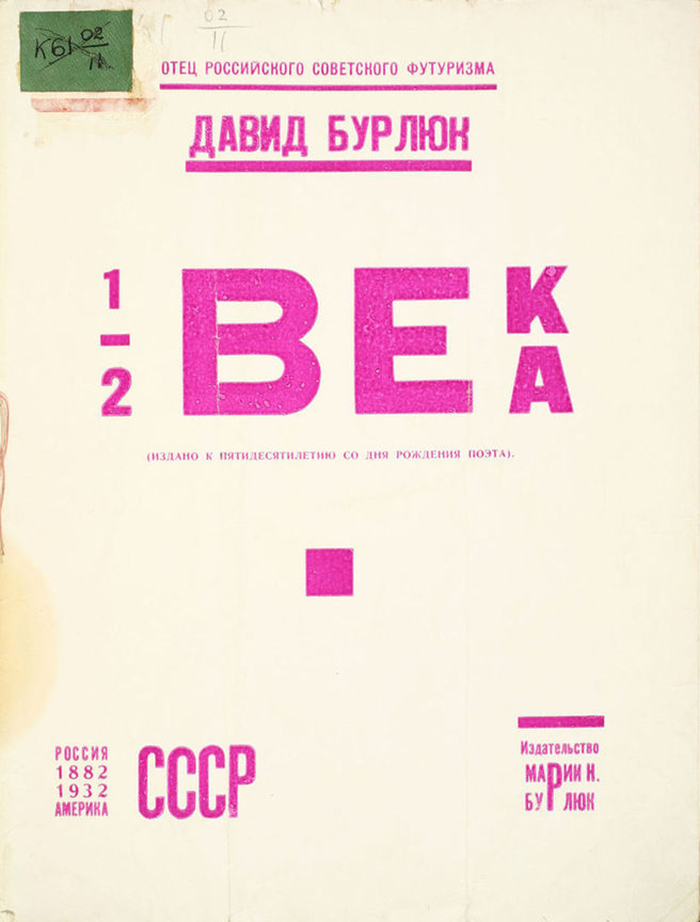

David Davidovich Burliuk (1882–1967), 1/2 Century

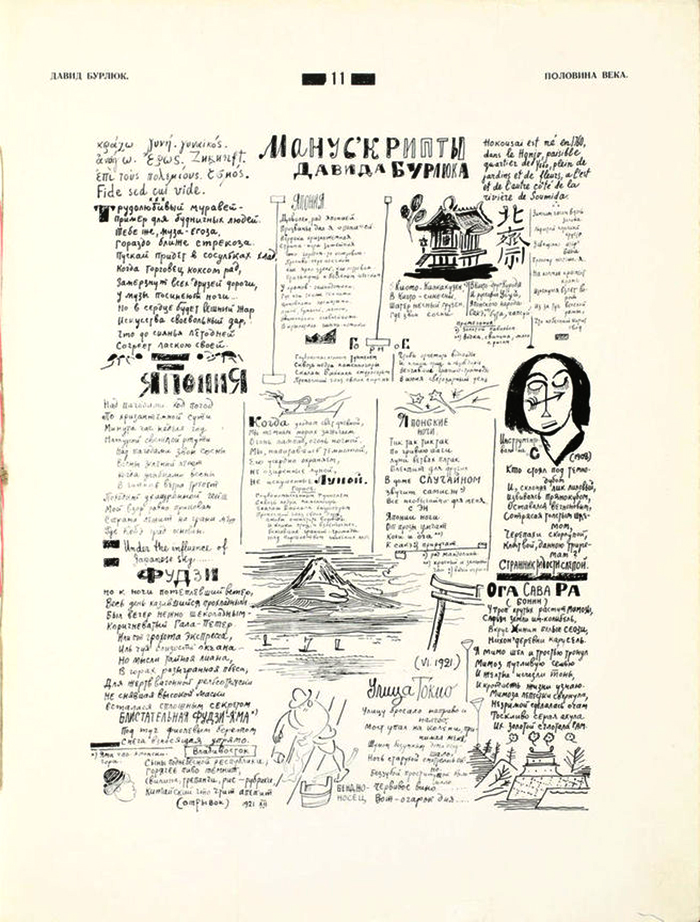

Interior of 1/2 Century

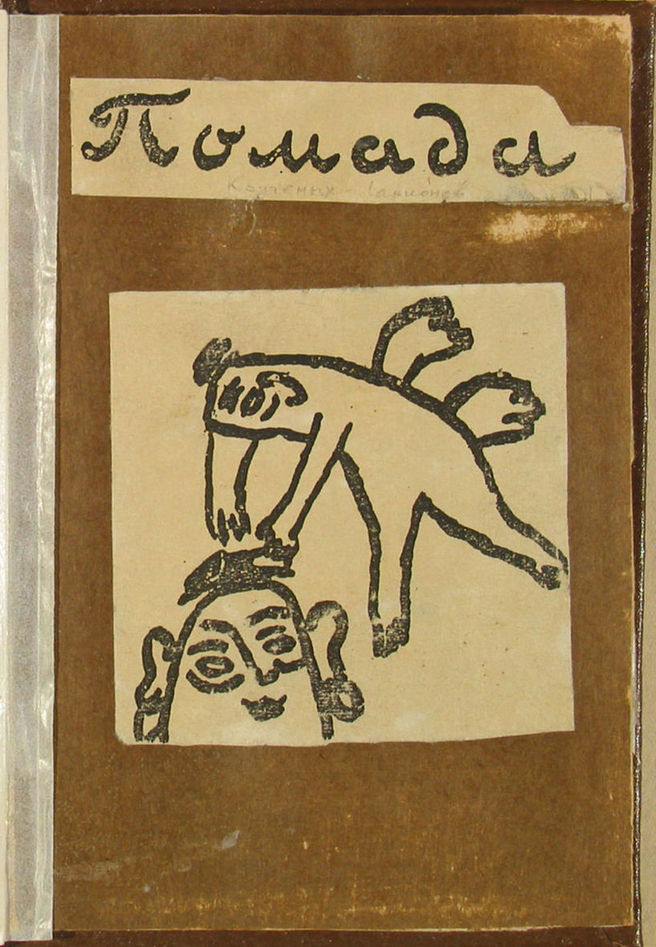

Eliseevich Alex Kruchenykh (1886–1968), Lipstick

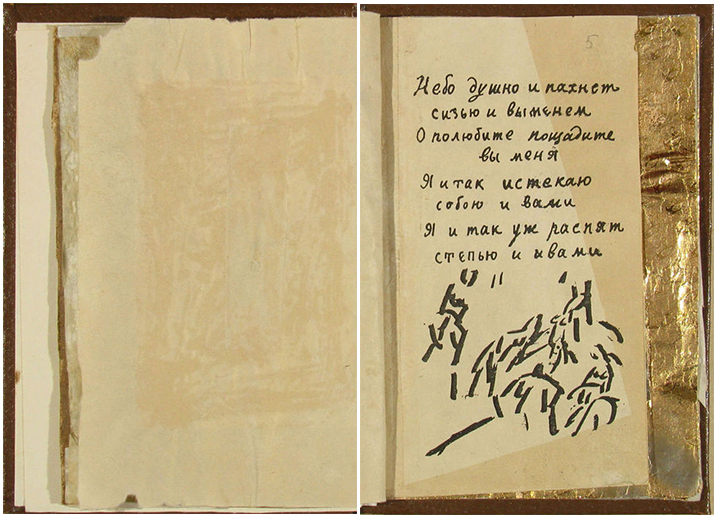

Spread from Lipstick

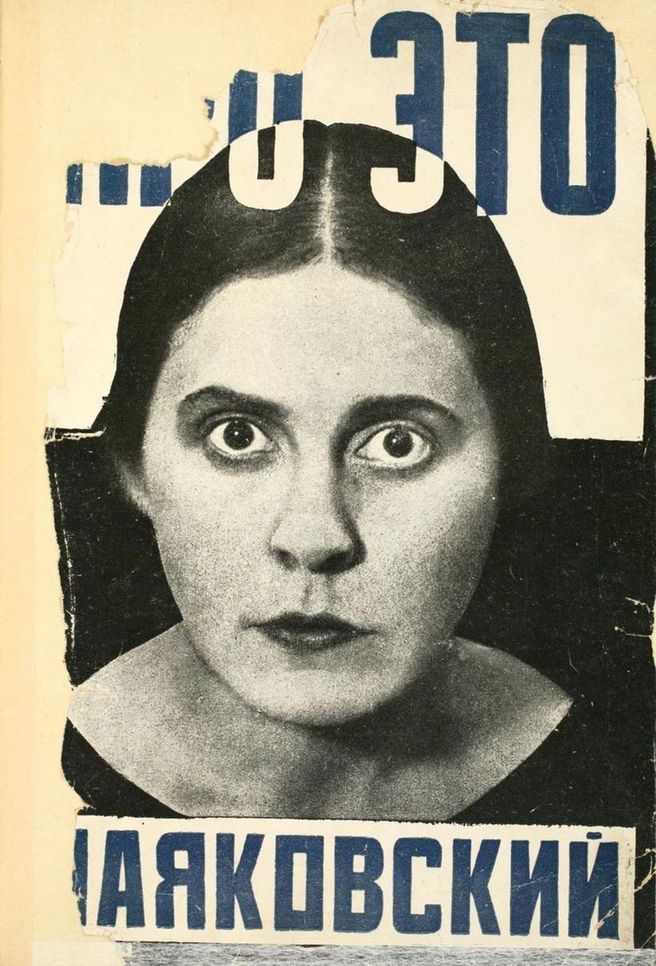

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1893–1930), About This

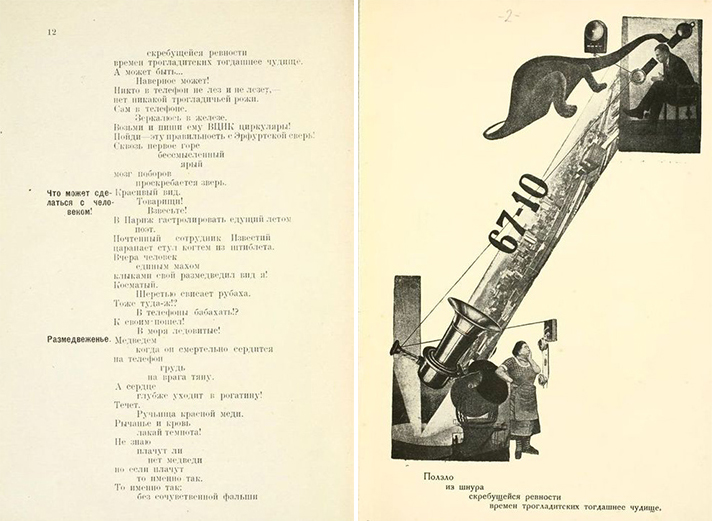

Spread from About This

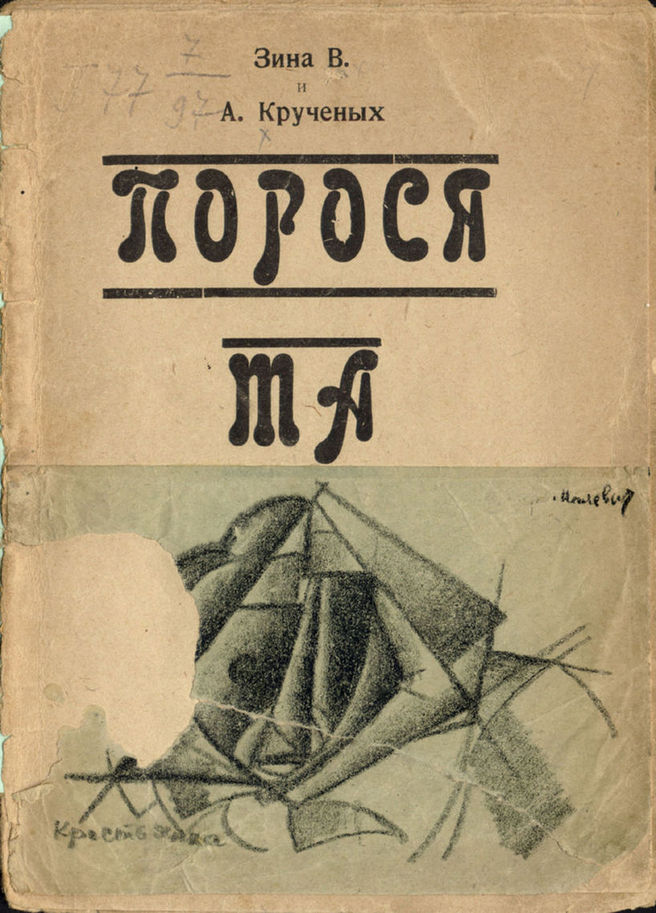

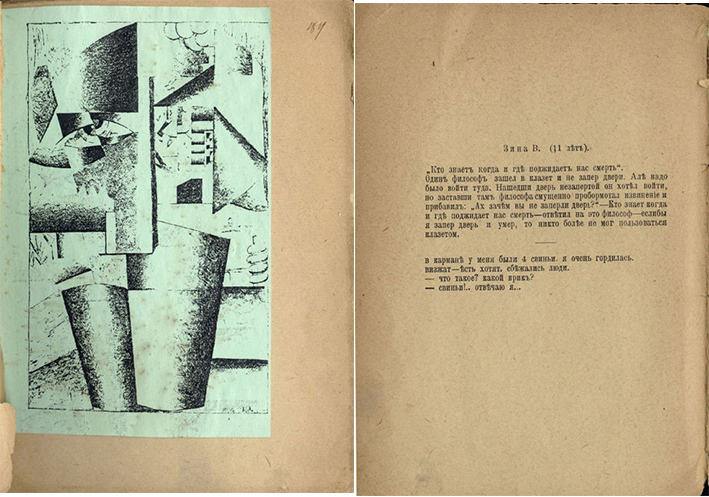

Eliseevich Alex Kruchenykh (1886–1968), Piglets

Spread from Piglets

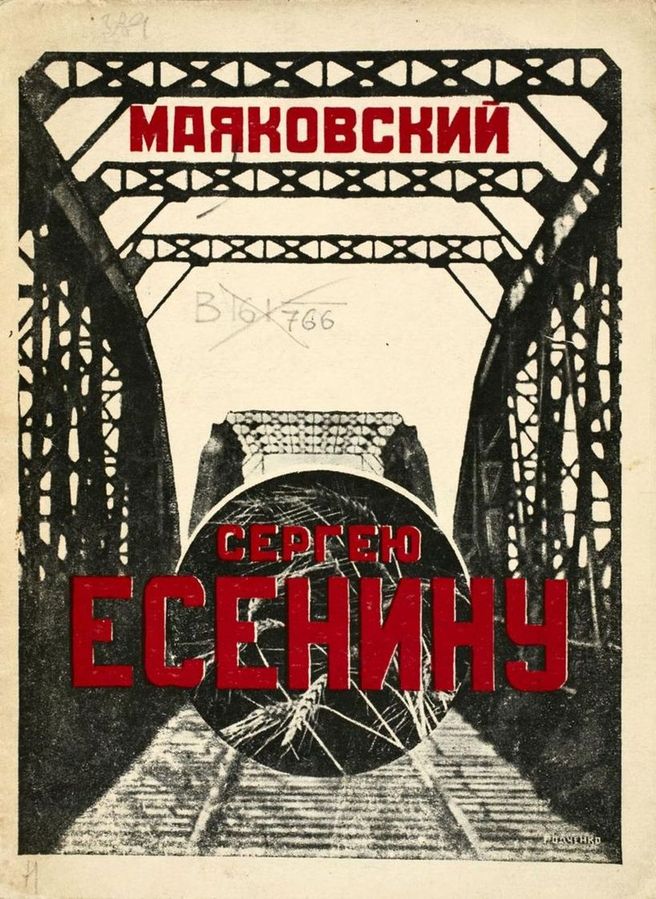

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1893–1930), Sergei Yesenin

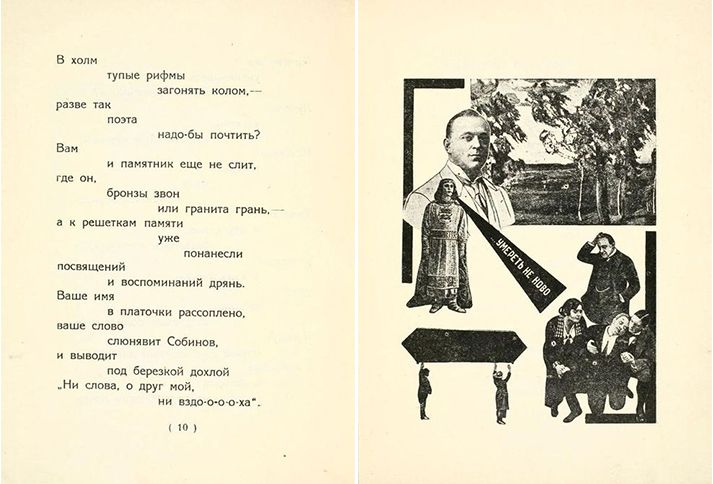

Spread from Sergei Yesenin

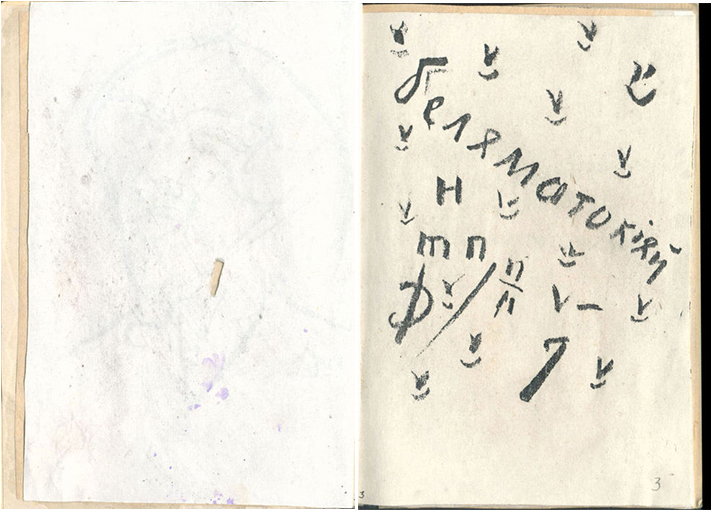

Spread from book by Alex Kruchenykh Eliseevich (1886–1968)

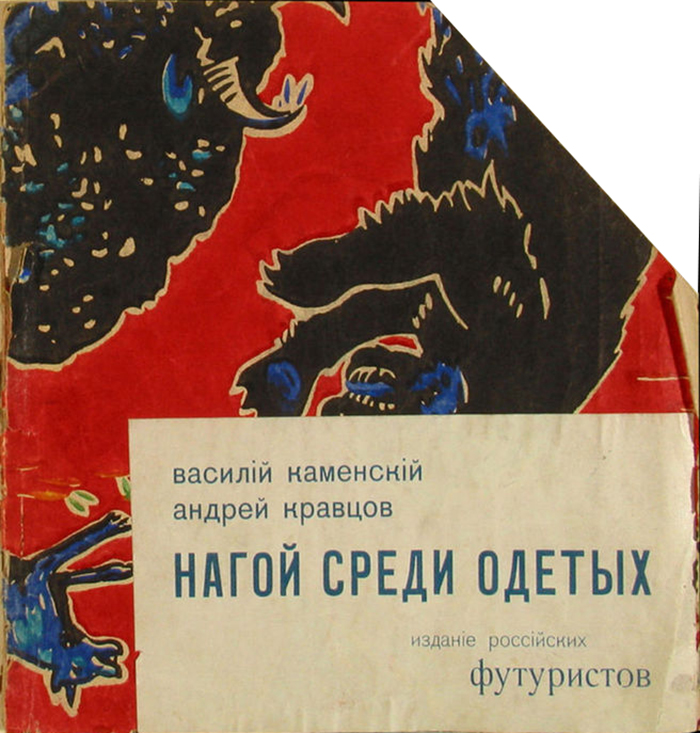

Vasily Vasilyevich Kamensky (1884–1961), Kravtsov Andrey

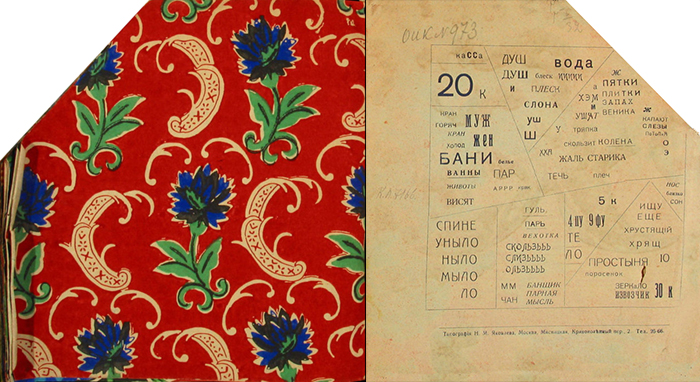

Inside spread from book by Kamensky Vasily Vasilyevich (1884–1961)