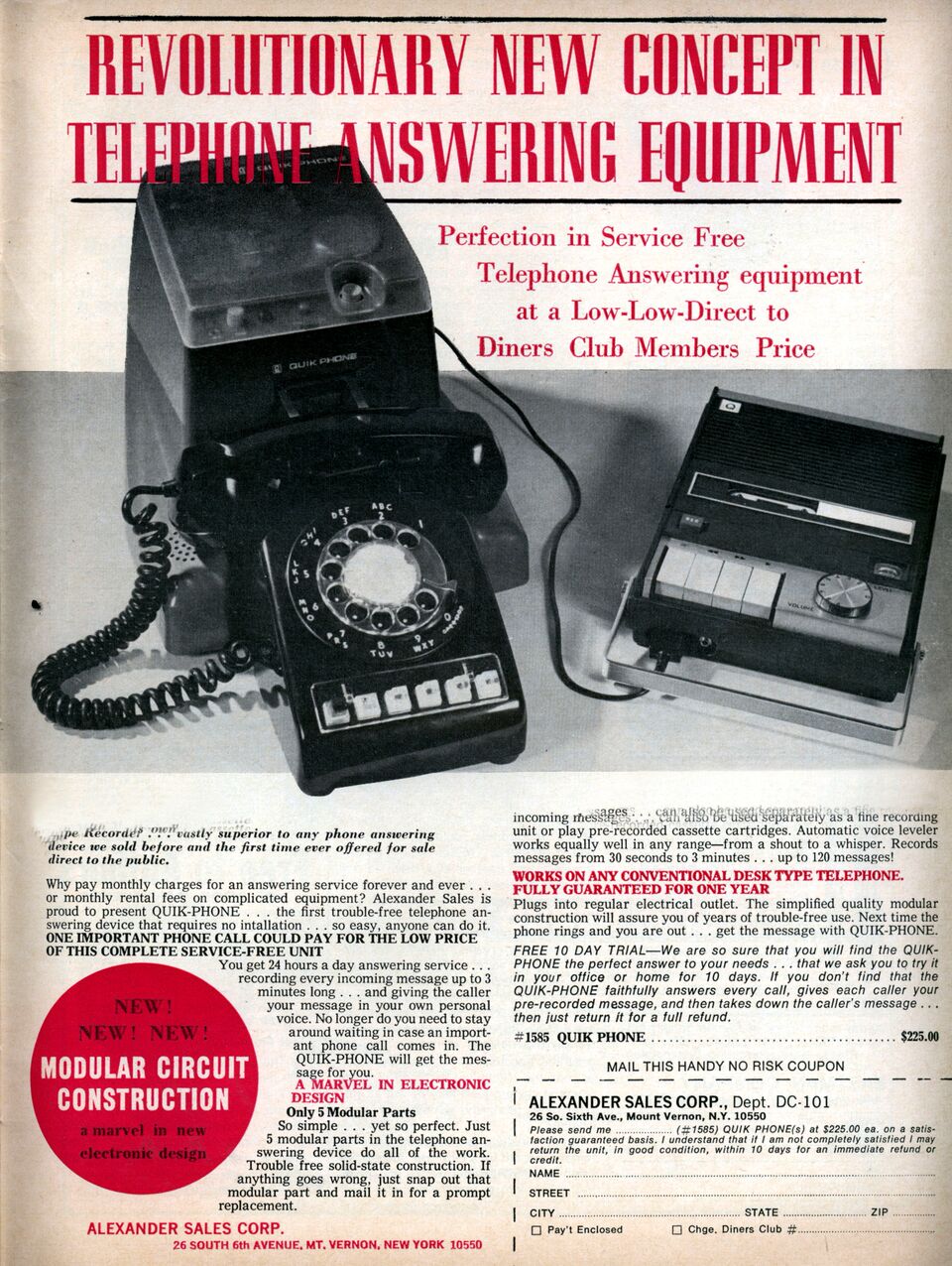

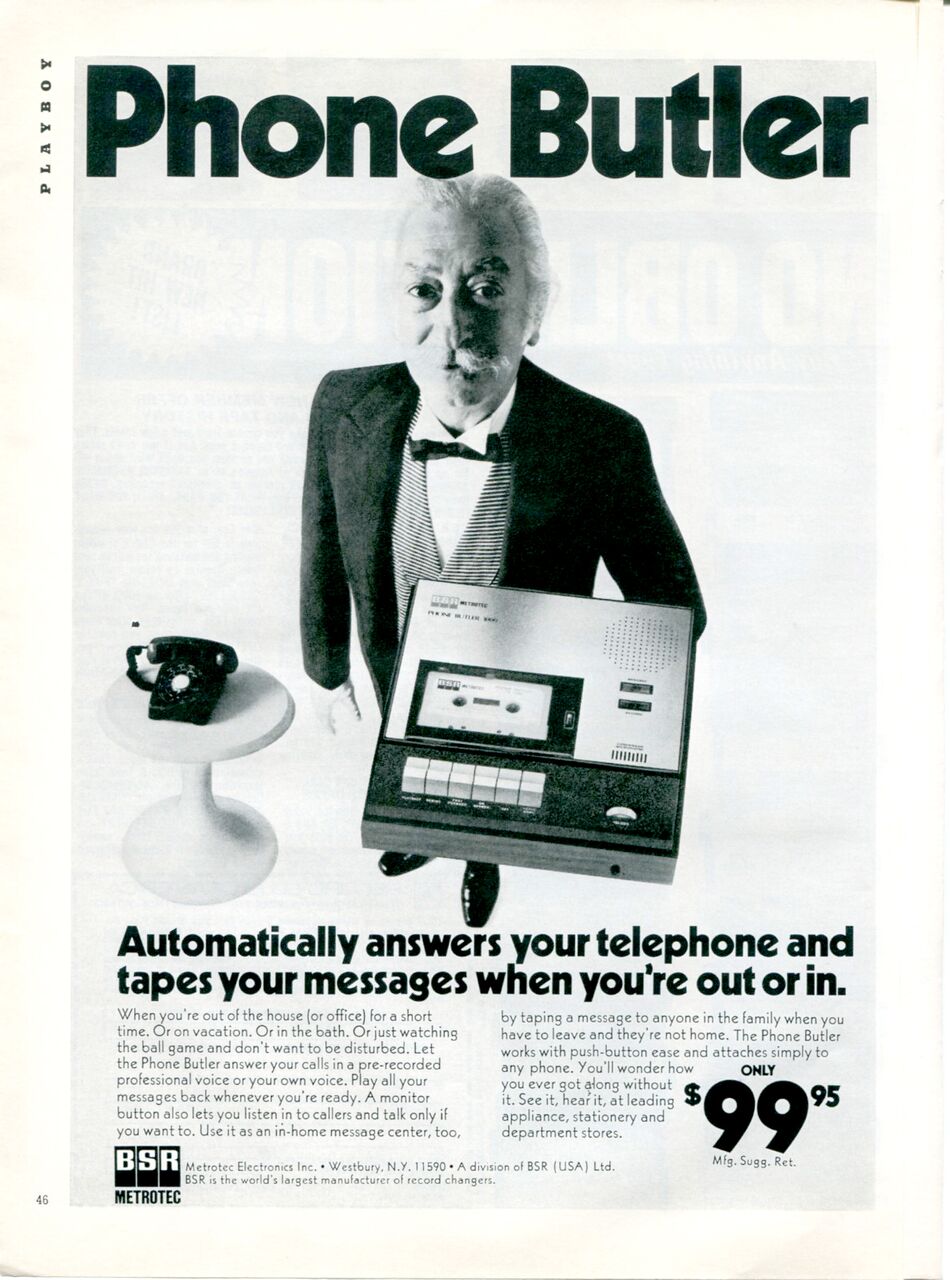

Thomas Edison once referred to the telephone as an invention that annihilated time and space, “bringing the human family in closer touch.” As a prognostication for the portable freedoms of the future, he couldn’t have been further from the truth. Today, our phones may be smart, but they’re hardly conduits for closeness. But where answering machines are concerned, he may have been rather prescient. When N. W. Ayer launched the “Reach Out and Touch Someone” campaign for AT&T in the late 1970s, it may well have been a response to the growth of answering machines like the one featured here: this one—published in a 1974 issue of Playboy and billed as a butler—was, like all of them, a programmable recording device that effectively eliminated the tether connecting you to your desk, thereby liberating from a kind of onerous, if involuntary house arrest. Answering machines were to the 1970s what VCRs were to the ’80s—a way to capture and compartmentalize time itself—that ultimately represented a significant paradigm shift with regard to personal scheduling and time management. Big and clunky, retrofitted with plastic cassettes and thick power cords, these machines were social media before we had the term.

You could be at home screening your calls, pretending not to be at home. You could get a friend to record your outgoing message in a funny voice. You could duck or posture, wax poetic, or call in sick without a GPS tag to smoke you out. Wait Wait—Don’t Tell Me, the NPR weekly news quiz, still lures participants by offering winners a chance to have scorekeeper emeritus Carl Kasell record their outgoing messages. Today, digital devices offer an essentially unlimited amount of message real estate, which you can dial in remotely to retrieve at will—but it was not always thus.

You could be at home screening your calls, pretending not to be at home. You could get a friend to record your outgoing message in a funny voice. You could duck or posture, wax poetic, or call in sick without a GPS tag to smoke you out. Wait Wait—Don’t Tell Me, the NPR weekly news quiz, still lures participants by offering winners a chance to have scorekeeper emeritus Carl Kasell record their outgoing messages. Today, digital devices offer an essentially unlimited amount of message real estate, which you can dial in remotely to retrieve at will—but it was not always thus.

Messages were once the raw material of so many of our lives. We saved the ones we loved, jettisoned the ones we loathed, replayed the voices we longed to hear over and over again. Linda Pastan, the former poet laureate of Maryland refers to this as “the accidental mercy of machines.” People didn’t poke or ping, post or tweet. They had voices, and they knew how to use them.

To read the complete article buy a copy of Observer Quarterly 1: The Acoustic Issue.