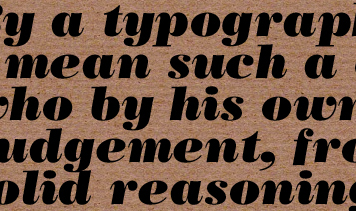

From Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises or the Whole Art of Printing, 1683-4. Letterpress broadside on paper towel, 1980.

When I was an undergraduate student and stumbled onto a course called Introduction to Graphic Design, one of my first assignments was to typeset — yes, with cold metal type — a quote by Joseph Moxon. As a typographic rookie, my understanding about the principles (let alone the nuances) of designing with letterforms was negligible, as were my research skills. Better investigative strategies might have led me to discover that Moxon was a seventeenth-century printer whose puritanical upbringing was reflected in a kind of zealous precision with regard to everything he touched.

Clearly, I didn't get the memo. So while my classmates produced elegant specimen sheets with evenly-spaced letterforms, I went into the bathroom, grabbed a few feet off the paper towel roll, and printed a long, scroll-like thing in 48-point Poster Bodoni Italic.

I was told I had no future as a designer. Today, my efforts would have been applauded.

Some years later as a graduate student in the same school, our first exercise setting type digitally required us to do the same thing on a composing stick: we made four book covers on a Vandercook, then with Moxonesque fastidiousness, duplicated our efforts in what I can only imagine was Quark 1.0. By then, my understanding of typography had perhaps matured, however marginally, and I used regular paper. But the prophecy stayed with me, its residual messsage boiled down to this: if you can't follow the brief, if you can't be responsible, if you can't follow the rules, you have no right being a designer.

Today, nothing could be further from the truth. And while the fundamental principles still apply, who would dare to suggest, in a classroom or elsewhere, that there are even any rules to follow? In the age of ubitquitous computing, the exigencies of computational rigor bring their own rules: code it wrong and it doesn't work. Tag it improperly and nobody can find it. But that's only part of it: the real shift is that following the rules only takes you so far. Even Paul Rand, that most orthodox of principled designers, knew this: "You must first know the rules," he once said, "and then break them in an intelligent way."

But who is to say what's intelligent — or not — about rule-breaking? When I was a student, the assignments and their expected outcomes were intentionally conceived as chore-like, specific and frankly, narrow. This was the age of zero tolerance: deviation from a designated format was neither an approved approach nor an acceptable method. (Today, the opposite is more likely to be true: a student who does not expand his or her approach to a project is strongly encouraged to do so.) Odd, in a way, that the lion's share of my faculty then — a generation who came of age in a climate of wartime resistance and later, post-war optimism — should have been so resistant to what might have been much more experimental shifts in expression. (When Oskar Schlemmer made those goofy costumes for his Triadic Ballet, was he hailed as a visionary or reprimanded for disrespecting geometric purity?)

This strikes me as a chapter in the social and cultural history of this profession that has yet to be examined. There was, twenty years or so ago, a certain amount of consensus around the notion that imposed limitations bred a certain amount of freedom. Good work emerged when the tension between structure and freedom was clear: this was, after all, one of the fundamental goals of the page-grid, an armature or foundation upon or within which the content — of, say, a book or a poster — could be safely placed. Similarly, such a predisposition was in many cases a kind of essential component in curriculum-building: the rule-based brief was intended to promote an awareness and understanding of principles: color, balance, harmony, composition, hierarchy, symmetry, etc.

What a bore. Today, you can go pretty much anywhere online and get a crash-course in things like the "rule of threes" — the fast food equivalent of a design degree. More committed design students pursue a different path, matriculating in programs across the world in which design is examined in a much broader, more inter-disciplinary context. Making form is no longer framed by the kinds of principles that characterized my own education, and it's a good thing, too. The world has changed a lot since Ronald Reagan was in office. What a relief to know that design has changed a little, too.