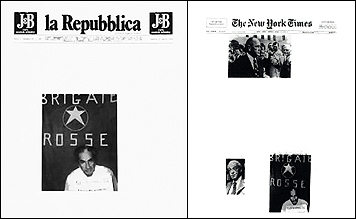

In the series Modern History (1978), the artist Sarah Charlesworth photocopied the front pages of newspapers and reframed the news by blocking out all the text, leaving only the masthead and photographs in their relative positions.

The recent controversy over whether or not to air the photographs sent to NBC News (sent posthumously by Cho Seung-Hui, the Virginia Tech gunman) reignites the moral paradox at the core of all crisis reporting. War correspondents, photojournalists and media pundits have long fretted about such decisions, which present countless questions about empathy (a subjective sentiment) and ethics (an objective obligation) and remind us that pictures, in case you were wondering, are profoundly complex.

Right or wrong (and one could argue both or either), the stills of an angry 23-year old wielding twin handguns on camera are just as disturbing as the images of bodies hurtling out of flaming windows on 9/11. (Some might argue that, because the killer himself both took and mailed the pictures to NBC, they are more disturbing.) It is perhaps fair to suggest that both events — along with their indelible imagery — have now been assured their respective places in the picture pantheon of modern-day tragedy. But does that mean they should be blasted across the front page of every newspaper all over the world?

Twenty of the world's largest news websites place the dominant homepage image in the upper left. Source: Eyetrack III, 2003.

When does a picture solidify a news story, and when does it merely sensationalize it? After seven-and-a-half hours of deliberation, argument and what we can only hope was a fair amount of soul-searching, NBC News "selectively chose certain limited passages and material to release" because, in the words of one of its more seasoned journalists, "We believe it provides some answers to the critical question, why did this man carry out these awful murders?"

Decisions about words and pictures are made by editors and publishers, designers and photographers — but they are consumed by a public fully capable of an entire range of emotional responses. Widespread misinterpretation is just as possible — indeed, as plausible — as any of the intended communications that we expect from our news media. (The growing speculation that Mr. Cho's media overexposure could so easily lead to copycat crimes testifies to this epidemic, especially if you're one of those people who thinks that there's too much crime on television anyway.) With the advent of citizen journalism, viral video and blogging, this territory grows even murkier: truth-telling, factual evidence and reality itself are not so easy to identify, let alone assess. And yet, whether by habit, instinct or sheer impatience with reading, we routinely assume that pictures speak louder than words. To this end, the labor-intensive research studies undertaken by the Poynter Institute and the Eyetrak team remind us how people look at computer screens and television screens and yes, at newspaper pages. Such studies present objectified data and thereby reinforce what many of us may have already known: bigger is usually better. Further evidence reveals that the space occupying the top left is privileged real estate.

Yet as reassuring as it may be to know this, it doesn't really go to the heart of the problem. It is hard to imagine that the repetition of Cho's likeness — a visual cue for the massive murders at his hand — would have been any less demonic had it been nudged to one side. Simply put, it's not an issue of placement so much as one of perverse saturation. And no amount of compositional ingenuity can possibly reverse that.

While testing 46 participants' eye movements across several news homepage designs, Eyetrack III researchers noticed a common pattern: the eyes most often fixated first in the upper left of the page, then hovered in that area before going left to right. Source: Eyetrack III, 2003.

In all fairness to the study, Eyetrack's disclaimer admits their research is "wide" and not "deep" — suggesting that it doesn't pretend to solve everything. Yet the news industry's preoccupation with how people digest information somehow begs the question: how does what we see — and the order in which we see it — affect us? And why should we care? Similarly, why do we need to look — if indeed we need to look at all? Perhaps because there is something about seeing the news that reminds us it's real, that it actually happened, and that there's material evidence to prove it. For multiple reasons (too much time to fill, for one) repeated exposure to the same story is the prevailing style in most 24/7 reportage. And so it goes, a tautological symphony of regurgitated images — ever expanding, never silent, feeding an incessant public appetite for tangible evidence. It's the new manifest destiny, greedy and territorial: this is truth by reiteration, not so much a reinforcement of fact as an annexation by conjecture.

Meanwhile, images — at turns cryptic and expository — engage our minds in ways both wonderful and weird. We take and make them, seek and share them, upload and publish them, distort and freeze-frame them. We are all visual communicators now: even Cho Seung-Hui chose to tell his story through pictures. (While NBC News claims its treatment was sensitive, the network also virtually cemented the killer's notoreity: as of this writing, more than twenty of the twenty-five leading news websites cited in the Eyetrack study posted either Mr. Cho's photograph or a portion of his video — or both — on their sites this week, many of them on the homepage.) Mercifully, serious and responsible journalists — and God bless them for this — remind us that veracity is a core conceit of the news: words and pictures don't tell just any story, they tell the story — the real, raw, newly-minted facts that deserve to be told. In this view, pictures of a gun-flinging madman may indeed have their place. But to the untold scores of people whose lives have been forever scarred by a senseless, incalculable human loss, these pictures are gratuitous and terrifying and mean, no matter how big, or small, or aligned to a left hand corner. And shame on all of us for needing to be reminded why.