This essay was first published on October 6, 2008.

The spring of my junior year in college, I decided that the ultimate fulfillment of my two passionate interests — Italian and graphic design — could only be met through the deft maneuvering of post-graduate study at the Politecnico in Milan. Heading into what was clearly an economic recession, I figured the other side of the pond held enormous potential for my newly-minted approximation of adult life: affordable food, cute guys, a 24-7 chance to practice my Italian and — oh yes — advanced study in my chosen profession. It was, by all indications, a win-win situation.

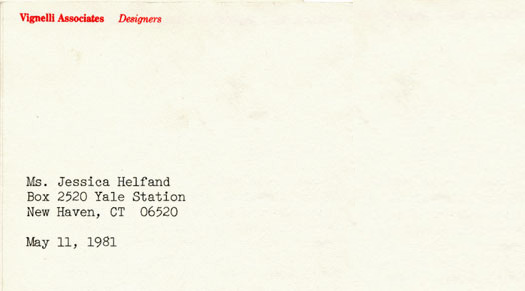

Yet even more brazen than this was my decision to ask for advice outside the confines of my narrow, yet fairly solid pantheon of advisors. No, I didn't ask my parents, or my professors, or even a number of rather sensible grad students I knew at the time. Instead, I headed straight to the top, and wrote to Massimo Vignelli.

And he wrote back.

A century from now, when the current climate of celebrity bad-boy culture is written up as the self-immolating series of disasters it so often seems to be, such examples of kindness may be so rare as to be altogether forgotten. Common wisdom suggests that celebrity is inversely proportionate to generosity, and time and time again, star antics bear this out. At the unparalleled top of the heap are movie stars (and the paparrazzi who stalk them) followed by professional athletes, musicians and — this just in — the newly deprived financiers of Wall Street. From last year's Alec Baldwin to last week's Christian Bale to this week's Bobby Brown, it's a foregone conclusion: anyone really famous can't be nice.

Arguably, where designers are concerned — and here I am referring to famous designers — there may be evidence of a similar trend. I have seen my share of pretentious, affected, and indeed, nasty designers, who see themselves as somehow superior to the younger, unseasoned types of people who occasionally approach them for advice: in fact, I've been meeting people like this most of my adult life. Some of them were my teachers, others my employers, and all I can say as I approach that abyss of transcendant self-awareness (as far as I can tell, the only benefit of my incipient slide into middle age) is that it was absolutely not necessary for any of these people to treat me as a slave, or a half-wit, or a peon in their exalted, myopic universe. And yet, they did.

So how to explain people like Massimo Vignelli, who didn't know me, who had no reason to write back to me, but did? Or Bradbury Thompson, who annually treated his entire class of thirty-plus graduate students to lunch? Or, for that matter, Steve Heller, who found time from publishing a new book, say, every fifteen minutes or so, to give me my first break as a writer? I was once even the beneficiary of the famously charitable designer/writer/humanitarian Dave Eggers, whose unsoliticited email I've always been tempted to frame.

Email from Dave Eggers, following the publication of Reinventing the Wheel.

I have heard that Milton Glaser will never accept a social invitation if it means canceling a class, because his students come first. This makes him a rock star in my book, and makes me wonder if we should start teaching ethics in design school. If charity begins at home, how can we proclaim new and progressive agendas of social change without examining ourselves, our students, our profession?

Consider the alternative. Some years ago at a charity event, a certain well-known designer (who shall remain nameless) maneuvered his tall, slender frame past me in order to ensure himself strategic proximity to a particular item in the silent auction. He shoved. I fell. He won.

I was about 7 months pregnant at the time.

How about the tale of a certain well-known design studio in New York City, whose partners literally stole an intern from another, perhaps equally (if not more) well-known design studio? I wish I could report that the names of the offending studio partners were mud, except that such mudslinging would have required cooperation in stooping to this level. Which, as it turned out, the owners of the other studio refused to do.

True, it is much more common — and clearly more fascinating — to hear tales of the abuse of privilege, stories of the kinds of trainwrecks and disasters that fuel tabloids in a way that actual kindness inevitably fails to do. Even blogs aren't inuired from this condition: speaking about this with Ellen Lupton and members of her graduate class at MICA last spring, the consensus was that snarky comments from our readers here on Design Observer are much more engaging to peruse. All true, and even understandable: such is the foundation of any provocative, spirited debate. At the same time, I suspect that most of our contributors (myself included) probably prefer substance to snark.

True disclosure obliges me to report that the same individual who resisted the aforementioned mudslinging was, in fact, equally generous when it came to me. A few years after my dreams of grad school in Italy were pragmatically dashed, I was back at Yale and — knowing of his appreciation for Bembo — I sent him a floppy disk with a digital variant that a classmate had designed. It sent a nasty virus spewing through at least a dozen of his studio's computers — a fact which, notwithstanding, resulted in his sending me a beautiful thank you note acknowledging my gift. He didn't avoid my calls, or vilify me for my inexcusable transgression, or pull the kind of rank he so easily could have pulled given the fact that he was well-known and I was, frankly, a nobody. "So maybe my next call should come during a trip to New Haven and we can have another brunch," he wrote on his studio's elegant letterhead. I used it as an excuse to phone him and ask his advice — over brunch, maybe?

Turned out he wasn't free for brunch. He was, however, free for dinner. And a few years later, he married me.

Yet even more brazen than this was my decision to ask for advice outside the confines of my narrow, yet fairly solid pantheon of advisors. No, I didn't ask my parents, or my professors, or even a number of rather sensible grad students I knew at the time. Instead, I headed straight to the top, and wrote to Massimo Vignelli.

And he wrote back.

A century from now, when the current climate of celebrity bad-boy culture is written up as the self-immolating series of disasters it so often seems to be, such examples of kindness may be so rare as to be altogether forgotten. Common wisdom suggests that celebrity is inversely proportionate to generosity, and time and time again, star antics bear this out. At the unparalleled top of the heap are movie stars (and the paparrazzi who stalk them) followed by professional athletes, musicians and — this just in — the newly deprived financiers of Wall Street. From last year's Alec Baldwin to last week's Christian Bale to this week's Bobby Brown, it's a foregone conclusion: anyone really famous can't be nice.

Arguably, where designers are concerned — and here I am referring to famous designers — there may be evidence of a similar trend. I have seen my share of pretentious, affected, and indeed, nasty designers, who see themselves as somehow superior to the younger, unseasoned types of people who occasionally approach them for advice: in fact, I've been meeting people like this most of my adult life. Some of them were my teachers, others my employers, and all I can say as I approach that abyss of transcendant self-awareness (as far as I can tell, the only benefit of my incipient slide into middle age) is that it was absolutely not necessary for any of these people to treat me as a slave, or a half-wit, or a peon in their exalted, myopic universe. And yet, they did.

So how to explain people like Massimo Vignelli, who didn't know me, who had no reason to write back to me, but did? Or Bradbury Thompson, who annually treated his entire class of thirty-plus graduate students to lunch? Or, for that matter, Steve Heller, who found time from publishing a new book, say, every fifteen minutes or so, to give me my first break as a writer? I was once even the beneficiary of the famously charitable designer/writer/humanitarian Dave Eggers, whose unsoliticited email I've always been tempted to frame.

Email from Dave Eggers, following the publication of Reinventing the Wheel.

I have heard that Milton Glaser will never accept a social invitation if it means canceling a class, because his students come first. This makes him a rock star in my book, and makes me wonder if we should start teaching ethics in design school. If charity begins at home, how can we proclaim new and progressive agendas of social change without examining ourselves, our students, our profession?

Consider the alternative. Some years ago at a charity event, a certain well-known designer (who shall remain nameless) maneuvered his tall, slender frame past me in order to ensure himself strategic proximity to a particular item in the silent auction. He shoved. I fell. He won.

I was about 7 months pregnant at the time.

How about the tale of a certain well-known design studio in New York City, whose partners literally stole an intern from another, perhaps equally (if not more) well-known design studio? I wish I could report that the names of the offending studio partners were mud, except that such mudslinging would have required cooperation in stooping to this level. Which, as it turned out, the owners of the other studio refused to do.

True, it is much more common — and clearly more fascinating — to hear tales of the abuse of privilege, stories of the kinds of trainwrecks and disasters that fuel tabloids in a way that actual kindness inevitably fails to do. Even blogs aren't inuired from this condition: speaking about this with Ellen Lupton and members of her graduate class at MICA last spring, the consensus was that snarky comments from our readers here on Design Observer are much more engaging to peruse. All true, and even understandable: such is the foundation of any provocative, spirited debate. At the same time, I suspect that most of our contributors (myself included) probably prefer substance to snark.

True disclosure obliges me to report that the same individual who resisted the aforementioned mudslinging was, in fact, equally generous when it came to me. A few years after my dreams of grad school in Italy were pragmatically dashed, I was back at Yale and — knowing of his appreciation for Bembo — I sent him a floppy disk with a digital variant that a classmate had designed. It sent a nasty virus spewing through at least a dozen of his studio's computers — a fact which, notwithstanding, resulted in his sending me a beautiful thank you note acknowledging my gift. He didn't avoid my calls, or vilify me for my inexcusable transgression, or pull the kind of rank he so easily could have pulled given the fact that he was well-known and I was, frankly, a nobody. "So maybe my next call should come during a trip to New Haven and we can have another brunch," he wrote on his studio's elegant letterhead. I used it as an excuse to phone him and ask his advice — over brunch, maybe?

Turned out he wasn't free for brunch. He was, however, free for dinner. And a few years later, he married me.