Anniversary street art features a blackboard with lyrics from a popular song, “Without the Communist Party, There Would Be No New China." Image courtesy Roman Sharf

On July 21, 1921, some 50 men, including an obscure educator named Mao Zedong, gathered illegally in Shanghai to form a party devoted to radical populist ideas. In 30 years, they wrested power from the Kuomintang, the Nationalist Party of China, and established the People's Republic of China. After a number of disastrous cultural and economic engineering programs that left tens of millions dead, and more than 20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) remains formidable, not hesitating to suppress any hint of opposition. With some 80 million members — more than twice the population of Canada — it’s the largest political party on earth, wielding control over a fifth of the world’s population and its second largest economy. On July 1, the CCP launched festivities marking its 90th anniversary.

Topiary design outside Beijing’s Wangfujing subway station. Photos here and below: An Xiao Mina

Recent coverage in The New York Times and Washington Post has focused on large-scale commemorative events. These are certainly visible, especially here in Beijing. Youku, China's YouTube-like video service, features a whole series of celebrations from CCTV, including dance routines and patriotic music. Tiananmen Square hosted tens of thousands revelers and contines to feature a flower-carpeted hammer and sickle that glows bright red at night for all on Chang An Boulevard to see. But accompanying these grand gestures throughout July were multitudes of smaller interventions, from newspaper banners to billboard messages on the approach to Beijing airport that temporarily colonized the platform normally occupied by commercial advertising.

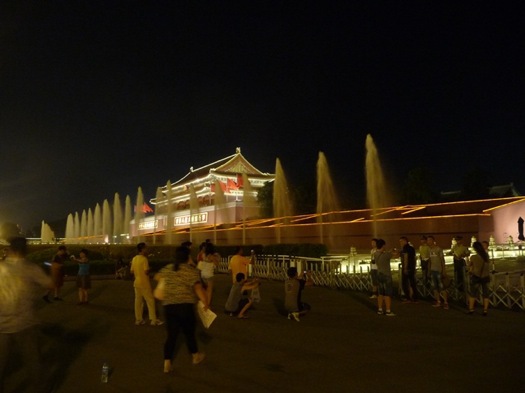

Across the street from Tiananmen Square, tourists snap photos beneath fountains spurting water in time to the music pouring out of loudspeakers.

Much is made of design for political campaigns in democratic countries, where a system of competing parties forces new innovations in the use of media. But what is the role of design in a one-party state? What does a campaign look like in a country where the people cannot elect their leaders? Tania Branigan, in a recent Guardian feature on the growing demand for Mao Zedong impersonators this month, shed some light on the celebrations: ...it seems necessary to keep today's members in awe of the glory of the past, hence a busy campaign complete with revolutionary tours, red song concerts and a new patriotic movie that sprinkles its account of the party's creation with a host of star cameos aimed at younger viewers. As the party moves ever further from its roots — the new film is co-sponsored by Cadillac — it exploits them to bolster its relentless, Leninist grip on political power."

In the heart of Beijing, near the Drum and Bell Tower areas, rickshaws bear bumper stickers exhorting the anniversary. This neighborhood is popular with foreign and Chinese tourists, but the messages are clearly aimed at a Chinese-speaking audience.

I moved to Beijing this year with stereotypes of Red Communism, as I pictured Mao's omnipresent gaze over the capital from his perch outside the Forbidden City. I've heard my fair share of hong'ge, or red songs, and I think of the Chairman every time I pull out a renminbi note. But in July, traveling around Beijing and then to Shanghai, Suzhou and Tianjin, I found the daily visual reminders of the CCP more subtle than I had imagined, even during this time of celebration. It felt closer to an advertising campaign than a traditional propaganda push.

Anniversary celebrations were less visible in Shanghai than in Beijing. On a cab ride, I hastily photographed this one promoting innovation and transformation in addition to congratulating the Party.

Commemorations in the Beijing subway blend into the general consumerist background — just another message promoting everything from banks to toothpaste to iced tea.

The media strategies are “not that new,” explained Anne-Marie Brady, a researcher of Chinese propaganda and media at the University of Canterbury. “The main model for the transformation of China's propaganda work is the West.” Since 1989, the Party's Central Propaganda Department has refined its messaging techniques, borrowing heavily from other nations. Professor Brady cited research from her forthcoming book, China's Thought Management: “China has also adopted many of the means of persuasion more commonly seen in Western democratic societies such as spin doctors, political PR, and careful monitoring of public opinion. The inspiration for China’s new policies have become increasingly eclectic over the years since 1989; the US, Japan, Mexico, Singapore, France, Germany, Sweden, and North Korea have all been models in different aspects of society, while the Soviet Union under Gorbachev and post-communism in Serbia, Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan have served as anti-models.”

Beijing Times developed a page one header highlighting the anniversary and used a similar format for section heads.

Throughout my wanderings in China, I've seen party slogans and logos comfortably positioned alongside product advertising. Anniversary messaging, the majority of which exhorts viewers to “warmly celebrate the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party” appears next to NBA star photos and McDonald's logos. On the subway, I watched a television feature on CCP history transition to a history of Michael Jackson music videos. As I clicked through online social media like Sina Weibo and Tudou, I saw web banners prominently displayed that evaporated with a click.

On Beijing's oldest subway line, small TV screens featured videos narrating the party's history. A few minutes later, the screen switched to clips from Michael Jackson music videos.

The photos displayed here offer a glimpse of these design strategies. From instant messenger cartoons to rickshaw bumper stickers, the 90th anniversary celebrations have been a multi-platform effort. China’s radical experiment in leadership, now almost a century old, is interwoven with high-speed trains and sky-high skyscrapers, with blockbuster movies from Hollywood and Hong Kong, and with microblogs, IM and 3G iPhones.