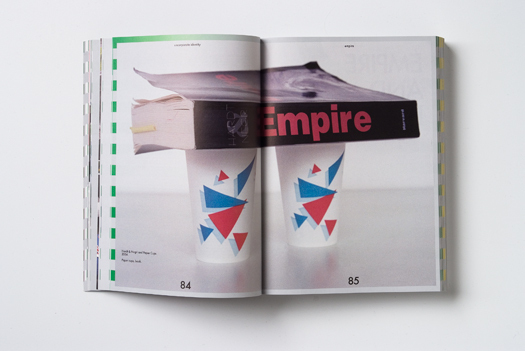

Daniel van der Velden, Society of the Query, 2009

I first met Daniel van der Velden in Brno, Czech Republic, in 2008. Among a group of outstanding designers presenting at an International Biennial of Graphic Design, I was struck by the content of Metahaven's work — politics, borders, immigration, social networks and economic theory. Metahaven is a partnership of Daniel van der Velden and Vinca Kruk (whom I recently met in Amsterdam). I have also written about a recent Metahaven project, proposals for a new graphic identity for WikiLeaks.

My fellow Design Observer OBlog critic, Rick Poynor, has described them thus: "Metahaven is one of the most theoretically informed, strategically adept and articulate groups of thinkers operating in graphic design..." — high praise from a writer who has challenged the current state of Dutch graphic design.

Daniel and I started this interview months ago when Uncorporate Identity was being published, and it dragged on as we attempted a sustained conversation by email, while we were both traveling over many months. While I share Rick Poynor's respect for the larger Metahaven project, I went into the interview troubled by some of their actual design work, as well as by the language that defines and surrounds their practice. If this interview seemed awkward and testy at times, it is probably because of these biases — which I brought into this dialogue, despite our many mutual interests and shared concerns. I have let the conversation stand as it happened, edited by both parties only for sense and clarity.

William Drenttel:

Daniel, let's start at the beginning. What is Metahaven?

Daniel van der Velden:

Metahaven is a design studio. Vinca Kruk and myself are the founders. We work together with other designers and researchers under the Metahaven name. We specialize in client-based work (publications and identities), research (which may be exhibited, printed or experienced online), and writing. Installations, art projects, communication strategies, texts, publications, interviews and public lectures are all part of our output and are situated under the general rubric of “critical design” — however welcome, unwelcome, acceptable or unacceptable such a term might be!

WD: A number of years into the practice, what are the distinctive talents and contributions of Metahaven’s two partners? What brought you together as a team in the first place?

DvdV: Our first projects dealt with the confrontation of a place — a fixed location on the map — with a flow of images, ideas and information. That place was Sealand, a former anti-aircraft platform in the North Sea, which was proclaimed an independent principality in the 1960s. Since the early 2000s Sealand has tried to be a data haven and an offshore bank, after having attempted to become a casino. A few years ago it was put up for sale on eBay. The Pirate Bay tried to buy it. Through Sealand’s online image economy we wanted to bypass the idea of a centrally organized corporate identity. Think of the difference between a corporate brand manual and a Google image search on that brand. Vinca Kruk and I, having worked on the Sealand project, realized that we wanted to do more with this idea than a one-off try at “design research.” For the past three years, Metahaven has been our full-time practice. What brought us together, aside from this concrete assignment or case study, was an interest in speculative design. The idea of fantasy and fiction being an important part of what defines a project.

WD: Is there something about how you work that suggests the abstraction of the traditional design studio as a physical place? Or it’s mutation into something networked and decentralized? When you describe Metahaven as a studio — as in artist studio, design studio — does that have historical meaning for you today? At Winterhouse, I know we’ve always struggled with whether we’re a company or a firm or a studio or an institute — but the place or space was always a big part of our life in design.

DvdV: Currently our home base is Amsterdam, but we are traveling quite a bit. The place is important — wherever it is. Our studio is located in an interesting area that is less quaint and picture-perfect than the cliché image of this city. Being based in Amsterdam, however, doesn’t make our work “from Amsterdam.” It is tempting to think that it could be from anywhere — while we share some roots with Dutch design culture, there is a sense of that culture now having become global, or at least having assumed a global style. I also would like to try to de-mythologize the idea of a networked studio. Of course a networked studio is a wildly interesting idea, and don’t we all love decentralized and leaderless networks so much more than bureaucracies and other pyramid structures — let’s say the Tea Party vs. Total Design? But the more a studio is decentralized, the more it needs coordination and management. If you are working from different locations, then your coordination standard — or set of online tools — replaces the common space you would share in a more traditional office or studio environment.

WD: I’m sure this will come up again, but since the Metahaven starting point was “a shared interest in speculative design,” can you define “speculative design”? As opposed to what? Who else does speculative design today (or in the past) that you respect? Is design research the larger description of the practice? I suspect “design research,” too, means something specific to you.

DvdV: Design as a tool used to inquire, to research, to anticipate. Also, design as an instrument to imagine. In our understanding, the idea of “speculation” even includes just pitching for a new project, a process which many designers hate (and some clients love). Any design pitch is somewhat speculative. It gambles on the probability of future events; either a particular idea about the entity making the commission, or just the question of whether the proposal itself will be selected to become a reality. A web platform like Crowdspring, and its rising popularity among both clients and designers, shows how the pitching landscape is being reorganized. When discussed from the point of view of critique, speculative design anticipates a reality, and uses that as a critical device. That is where it really differs from pitching. Most well-known speculative designers so far have been architects. Groups like Archizoom, with their seminal No Stop City, but also earlier urbanists like Ludwig Hilbersheimer, drew urban plans that reflected political critiques of society. Speculative design presents science fiction in the here and now — think also of people like Alvin Toffler. One design approach we feel quite affiliated with is that of the British duo Dunne & Raby, whose work relates to technocracy, guided by personalized approaches to well being and risk management. We also feel affiliated with groups like Slavs & Tatars, although you might argue that our work is a little less geared toward fiction and a bit more about reality. In our work, reality is interesting because it approaches fiction; because reality often provides the strongest form of fiction. Then “design research.” You can research by design, or research for design. We try to do both.

WD: Twelve exhibitions, scores of presentations, more than a dozen “editorial and curatorial projects”: How has Metahaven managed to assemble such a large body of work in only a few years?

DvdV: The question sounds like we have done something physically hard to accomplish. Maybe that is true. Maybe it isn’t. We are all hard workers, I guess. We enjoy what we do.

WD: In your mind, is there a difference between projects you research and those you actually design and produce? And what about making a living? Are you carving out a niche of “other” work that pays?

DvdV: What we do in self-directed or research-driven projects, or in projects that don’t have a client approval at checkout in the traditional sense, is apply a set of interests that generate content. The same energy is brought to commissioned work, too. But in any client-based project the outcome is always informed by the client’s wishes and the limitations set by time, scope and budget. Often these limitations do make the actual design outcome better, but we can only really know if we see alternatives. Metahaven is always about the production of alternatives. There is no hidden niche of work; it is more about keeping the overhead low. But honestly: I am not sure whether the economical survival of a group of experimental designers is such an interesting subject for readers. Maybe you think it is.

WD: I am always surprised by the degree to which readers want to know how people make the work they make in their studio (process), how they acquire those projects (new business), and how they earn a living (finance). I’m interested in not ignoring the question, but approaching it from the standpoint of innovation. We just ran a profile on Catapult Design, a new design firm working on an NGO model, and they revealed that they only made $59,800 in year one (66 percent in donations and only 8 percent in earned income). Revealing those numbers added an important dimension to the reporting because it placed their work in a context of scale — and demonstrated that their projects are supported by a new donor-based model. So let me pose the question in a different way: as Metahaven explores new models to do speculative design and commissioned design research, have you had to invent new financial models for working with clients or partners?

DvdV: Clearly many of your readers are designers. They want to hear about the nuts and bolts of a studio rather than listening to airy waves of self-branding. They see how the field is changing and want to know how other designers deal with it. And all that is totally legitimate. However, I would like to look at what we are from the work we make rather than from our salaries. Our business model is this: you have to take everything as an opportunity and be very entrepreneurial about your work. You have to mix paid assignments with self-directed work; don’t assume that self-directed work is going to be the final solution. It won’t be. Design and clients belong together. We agree with Guus Beumer, Dutch curator and design writer, that redesigning design is not just up to the designers, but also up to the clients: if we need different answers, we also need different questions.

We do not currently rely on donations, but on “for profit” design commissions, research grants, writing and teaching. Vinca teaches editorial design at ArtEZ, a design school in Arnhem, The Netherlands. She also is a mentor at the Design Academy Eindhoven IM Masters, an interesting and influential program the output of which consists of concepts that may become products or services. I teach at the Sandberg Institute design department — the master program of the Rietveld Academy. And since 2007, I have been a critic at Yale University’s MFA in Graphic Design. This is an outstanding and inspiring place for every reason I can imagine. Neither Vinca nor I have a fixed job contract of any meaningful size anywhere. We rely on the trust and support of clients, partners and institutions.

The Sealand Identity Project, 2004 from Metahaven, Uncorporate Identity, 2010

WD: Let’s talk about your work, then. Your Sealand project in 2004 helped put Metahaven on the map. Looking back at the project, do you find it iconographic of your work — “Oh, those are the folks who created that country in the North Sea”? Has such a well-known project proven helpful or a burden to accomplishing new work? Are you planning future projects concerning Sealand?

DvdV: We will soon start a design project about an international organization that does the type of things Sealand originally hoped to do as a data haven. [WD added after publication: see WikiLeaks post here.]

WD: Your work reveals both respect for and deep suspicion of the power of borders. Did that interest derive from your graphic design proclivities, or is design the medium through which you express long-held, deeply rooted philosophical insights?

DvdV: A border on a map is, literally, a graphic device. It is the line dividing two territories. I guess we have always been into borders because they do politically what graphic shapes do visually. Design is absolutely the medium to grapple with this kind of issue. Despite the fact that we live in a connected world of mobility — or maybe even because of it — the power of borders is increasing. Border protection is on the rise, not just geographically but also electronically. Our book Uncorporate Identity contains the example of European countries boasting colorful, Miro-styled tourist identities, while in African countries, these same countries broadcast shrill, dystopian video clips saying: “Don’t try to come here.” An open door for one person is a closed gate for another.

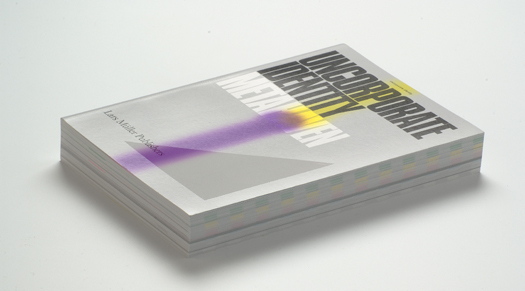

Metahaven, Uncorporate Identity, 2010

WD: Given your interest in the shifting identities occasioned by the European Union, what do you think of England’s first coalition government since World War II? Is it a reflection of contemporary Europe’s increasing fluidity, or of an increasing fracturing of political discourse?

DvdV: We are really interested in the new British government. No doubt it will provide a model for reforms elsewhere. Our 2009 project Stadtstaat referred, in terms of a visual science fiction story, to a Facebook State — though set in Germany and Holland. The Conservative campaign ran an incredibly glib and smartly-crafted rhetoric of Thatcher meets Obama. Unsurprisingly, we heard some ideas that would make F.A. Hayek — the father of neoliberalism — smile. But we also heard ideas we know from people like Cass Sunstein, or Clay Shirky, or Charles Leadbeater, for that matter. The Conservatives have married Thatcher’s small government with crowdsourcing, “Fawlty Towers” with the TED speech. Being familiar with the language, I think the British are being sold a utopia consisting of austerity packages full of thin air. The problem, frankly, is not the embrace of social media by the government but the unbalanced view taken of social dynamics as a whole. That is where the utopian danger is. The state is an incredibly important filter, and if it gives way to social dynamics believing that these are always and universally good — just because there is now YouTube and Twitter, because people post their own content and are nice to each other in online communities — that is a mistake. Above all, it is a human experiment with anarchy. This is why we remade the original Sex Pistols “Anarchy in the UK” tour poster for Icon magazine, with Facebook, Twitter and YouTube featured as bands. It is why we have done projects like Stadtstaat. That said, before you dismiss me as yet another Westphalian hooked up to big government, I agree that something has to be done if public deficits are so high. There is no reason why governments should not reform, but the current strategy conceals the real deal: the mass transfer of risk from the public sector to the people. And the term “austerity” is just so uninspiring.

WD: Alice Rawsthorn recently caused a firestorm with a New York Times article that praised Metahaven’s work as “a quest for meaning in a Dystopian Era” while trashing the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum’s 2010 Triennial as “earnest. …too dry, too cautious, too back-to school.” I assume you saw the Triennial exhibition when you were in New York doing events around your new book.

What are your reactions to this show and what is says or doesn’t say about contemporary design? If you could have included one project from anywhere in the world that was not in the show, what would it be and why?

DvdV: I don't agree with your assessment of Alice Rawsthorn's review of our book Uncorporate Identity, and of that Cooper-Hewitt show. It seems highly exaggerated to call the review a “trashing.” What Alice Rawsthorn did was compare both projects — the show and our book — on the premise that they started from similar concerns yet answered them very differently. I don’t feel comfortable talking about the show on the terms you are suggesting, primarily because I haven’t seen it, although photographs of it looked very good, as did the list of participants. But mostly because to me it seems legitimate to give very different answers to concerns that in one way or the other inform all of us. Is it not a good thing that a global economic crisis inspires the Cooper-Hewitt and Metahaven to give very different answers to the questions that arise from it? I am absolutely for pluralism in that respect. I find the idea that “praising” one thing means “trashing” the other quite depressing. And again, I don’t think it is true in this case.

WD: I think you’re being humble, or maybe politely politic. Obviously, Ms. Rawsthorn wrote her review from the standpoint of comparing approaches — that was already a “pluralistic” premise. What was so surprising was that she invoked a small design studio in Amsterdam in introducing a critique of the National Design Museum and its important biennial exhibition. So maybe “trashed” is overly charged, but here in New York, well, people were surprised by the comparison, and by the degree and tone of the critique: “lacked … chutzpah,” “trounced intellectually by MoMA,” “too dry, too cautious, too back-to-school.”

Without having seen the show, is there anything you wish to add about the comparison between Metahaven and the Cooper-Hewitt? Minimally you should be proud that your work is framing a discussion across an ocean — a real border in your vocabulary. Isn’t there something very much of an “uncorporate identity” theme in the comparison?

DvdV: What you are asking of me is to review a review — one that juxtaposed our work to an exhibition I haven’t seen. It is true that we are a small studio and that Amsterdam is a much smaller city than New York. But New York has many tiny studios of two, three, four people. The fact that something is small, or comes from a small place, is indie, or underground, in my view does not inherently invalidate its comparison to something bigger and more recognized. Apparently the competition as you frame it is not just between New York and Amsterdam, but also within New York — exemplified by the comparison between MoMA and Cooper-Hewitt. Besides that, how many shows does the National Design Museum run every year? And the Cooper-Hewitt show also got its proper review in The New York Times later on.

WD: Uncorporate Identity wasn’t entirely spared in Alice Rawsthorn’s Triennial review. She wrote that it “wallows in … complexities.” For me, Uncorporate Identity seems unnecessarily dense, at times almost inpenetrable. I’m not talking about its theroetical language (“a concatenation of voids and other polemical shapes,” to quote an early sentence in the book). The book includes so much raw documentation that I have trouble finding projects or clear exposition of intent and learning — even regarding subjects that deeply interest me. I assume on some level you want the work to speak for itself, but in the world of your design research, why this piling on of documentation? In other disciplines, especially science, research is published with an abstract, conclusions and findings, methods and results, and finally discussion of issues, notes and references. Why place so little emphasis on conclusions and findings, much less on clear abstracts. In other words, why not publish research that is more like research?

DvdV: I disagree with your idea that Uncorporate Identity presents a “piling”of raw material and documentation but I do agree that the book is a dense reading experience and that raw material is part of it. Uncorporate Identity is not a textbook. Neither is it a self-help guide. The book crosses a wide range of topics all concerned with the construction of identity, and these do not end at a single conclusion, but rather point to a similar direction. Design deeply adheres to the certainties of form and corporate structure, but these certainties have been hollowed out and we need to go beyond them.

Presenting documentation and projects is part of what the book does, of course. Four years of research and making went into it. Incorporating this work straightforwardly is part of letting the book be the book and not trying to suggest a greater narrative than there actually is, other than by links that readers can find through some of the words, and by visual devices the book frequently uses — terms like “brand,” “network” and “management.” There are essays with the titles “Brand States,” “Europe Sans,” and “Symbol Squatting” that do draw conclusions, as does an interview with the former Sealand cypherpunk/hacktivist Sean Hastings, who advocates the necessity of bearing arms in his radically libertarian-authoritarian model of anti-statehood. There is also plenty of material about graphic design and identity, like the essay on black metal music and its logos. Have you considered that black metal music was played to prisoners in Guantánamo Bay as a form of physical torture?

To my knowledge, there is no other design book, except for Wally Olins’s writings on public diplomacy, that has taken serious issue with the branding-related concept and practice of “soft power” (a term coined by Joseph Nye). Other ideas Uncorporate Identity brings to the fore that have not normally been raised in the graphic design debate include David Singh Grewal’s contributions on “network power.” The premise of our book, and of the concept of “network power,” is that globalization isn’t the global distribution of political consent, but the global adoption of standards that eventually leave values and ideologies up for grabs. We think these ideas are relevant, even though the presentation is admittedly dense and people have to do some work to access them. The attempt should be made especially if we want designers to become more adept partners at talking to business and science, and if we hope that design is going to be asking the right questions in order to give better answers.

That said, the book never actually promises the reader anything like a scientific, or popular science research method, with abstracts and conclusions. On the contrary, the editorial strategy of a “concept album” is announced on the back cover.

Now that Uncorporate Identity is finished, we would like it to exist in the world. A few hundred are going to have an interesting new wrapper — look out for these. People will either love it or hate it. I think it would be best instead to go where our common interests meet.

WD: Well, our common interests are great or we wouldn’t be having this discussion. I remember seeing a marvelous presentation you gave in Brno and thinking, “Finally a design practice that is engaging politics, bringing discussions of graphic design into the terrain of mutating and emerging national and global identities.” Uncorporate Identity is complex and challenging, as it should be. The issues in the book are complex and challenging too. So this discussion is hardly about whether I like the book or not. But maybe it can be explained further, or maybe just discussed in a way that opens its complexity up to new readers.

A common interest, I suspect, is how we move the graphic design debate into these realms of politics and networks, and what the implications are for how we talk about such work. As you note, “People have to do some work to access [our ideas].” In our own practice, I am continually challenged by just how ill-prepared I am as a graphic designer to do substantive work in education and healthcare, much less in any zone touching hard science. Would you say a bit about how science plays a role in your work, and how you think it will create new challenges for your practice in the next decade?

DvdV: From that afternoon in Brno I remember your own presentation, along with Jonathan Barnbrook’s and Linda van Deursen’s. After my presentation you immediately advised me to show less work — I think, an early warning of our differences: your preference for clarity and simplicity, and mine for avalanche, at the time maybe even much more so than now. Your talk showed how you have always been compelled to do design yet are driven and inspired by non-design topics that ranged from poetry to politics. I feel related to that idea and familiar with its problems. I’d say, however, that is what design is essentially about. Design is about the world, other people, other things, via you the designer, the gatekeeper. You are the filter. In my view, one of the most intriguing books you designed is the National Security Strategy of the United States, created after September 11. This was a book you sent to me straight after we had first met in Brno. I think of it as a document with historical value.

WD: When I published the National Security Strategy of the United States in 2002, it was the act of a frustrated citizen who had the tools of graphic design and publishing in his hands. The New York Times had only published excerpts of this new U.S. policy, but it was immediately clear that this document, freely available on the White House website, foretold the future — America would engage in a war on terrorism on its own terms, without regard to international law or the Geneva Conventions. (The torture at Abu Ghraib was clearly foreshadowed here.) To publish it only 48 hours after the new policy was released (of course, after fixing a few typos in the original document) was the real accomplishment: making it a book moved it beyond recent news into another, more permanent zone. Ironically, it is the least interesting design we have ever created, but perhaps the most influential book we have ever published — it sold 20,000 copies the next year, all through private distribution. Looking back, I believe this was the first time I used my role as a graphic designer and publisher to further purely personal political goals, and with no client agenda or backing. This was not design research or a designer-as-author endeavor — this was simply an act of political outrage. The design was in the act, not the execution. I’d like to believe that publishing this blight on American values had an impact, but it was solid journalism (by writers such as Mark Danner, to name just one) that would ultimately tell the real story of this misguided U.S. policy.

DvdV: One obvious question in response would be how and if that political outrage for you needed to have a visual component. A designer is essentially a double agent. The core of design work has a Machiavellian, diplomatic quality that becomes stronger the more relevant it is. At the same time, we have principles, values, and even dogmas we won’t bargain with.

About science, if we want to look at that, we need to resolve some of the misconceptions about the scientific character of the humanities. In my view the scientific method consists of you trying to prove your own hypothesis wrong. We are, unfortunately, not even close to a scientific model for design or design research. But we can use the social sciences as an influence and source of information for some of the issues we want to tackle with design.

WD: The borders of design disciplines are themselves dissolving, and you have declared architecture more influential in your work than graphic design. Do you think there will be such a thing called “graphic design” in 20 years? Does that term deserve to go the way of “commercial art”? If so, what should replace it?

DvdV: “Design” will stay; I expect the rubric to absorb most of the smaller factions of design. The slow disappearance of the “graphic” prefix is now evident in places that emerge as new design economies and have not gone through the print stage first.

We have started work on a new publication. It will be about this Facebook State idea, and the way that social media are affecting political sovereignty and value, our lives being monetized into “reputation currency.” Do you have thoughts about the notion of “monetizing the social”?

WD: I’m fascinated by ratings and rankings. For decades here in America, the Nielsen ratings determined what we got to watch on television, and effectively how millions in advertising revenues were split among the media channels — “monetizing the media.” Network presidents fell on the swords of their ratings. But for viewers, this entire process was distant — explained in secret code and with an arcane vocabulary. But today rankings are in fact like monetary denominations. Lady Gaga beat Barack Obama to 10,000,000 Facebook friends yesterday. A visitor at Winterhouse showed me his 500 Tumblr friends today. Design Observer will reach 200,000 Twitter followers in the coming weeks. We are measuring our lives — and friendships — in a new currency of rankings and numbers. I think this is one very real aspect in which “monetizing the social” is moving across borders into the sphere of networks. (I can just see a new graphic currency built on this premise.) To turn the question back at you, are you seeing examples where such monetization is having a positive social impact? Or places where designers are at the center of such impact?

DvdV: What I respect about the work of Andrew Keen, author of The Cult of the Amateur, is that he looks at the consistency between the 1960s’ hippie ideology, the 1980s’ free market ideology, and the 1990s technology ideology — merging in the participatory and anti-authoritarian ideology of social media. And I think he is right about that consistency. Looking at these skyrocketing numbers of friends and fans you just mentioned, it is hard not to imagine that this “boom” in social capital might be followed by some sort of meltdown. Not because we have a rational reason to expect that to happen, but because that is what generally happens after a bubble bursts. I agree that social media and social currency do have a real and at times positive impact on how people organize themselves and “get things done,” but I am arguing for a balanced view of social dynamics. People do more than cuddling and socializing.

You can see that the engineers and designers of the system want something simple that is for the good; there is no reason to doubt their sincerity, but social dynamics are not always centered around good news, and they are not always in themselves good and for the better. The UK government already has had to disable a participatory feature in their website that lets citizens propose state cutbacks. The things that popped up in this section were silly jokes, and blatant racism. Now there is something very insincere about switching that feature off, if you claim to be about how people are instead of how they ought to be. Silly jokes and racism are part of human nature and hiding that under the carpet will not make them go away.

Technically social media require an interface or platform, broadband internet and a device to get there. The only actors who can switch off whole parts of the internet are governments (or corporations, or hackers). The more authoritarian a state, the more effective a social media platform is in helping to counteract that government. A liberated Iran means the end of Twitter’s revolutionary potential in that country. The fact that everyone uses social media doesn’t make them better, but it makes them more influential. Actors also gain quantifiable influence. You mentioned your obsession with ranking, so I imagine you glancing at your social statistics a little like staring at an investment portfolio that rapidly increases in value. You close your laptop and you know you’re relatively well off. Andrew Keen is right in identifying the parallels between free market capitalism and social media, because they thrive on the same dynamic. Currently in our studio are a few F.A. Hayek books around, and one by Glenn Beck. This link to capitalism brings us further into the idea of social currency. There is a lot of experimentation with alternative currencies and some of that is really interesting too. We’re interested in radicalizing the scenarios — like, what if you acquire not financial debt through unpaid credit card bills but social debt through unreturned generosity? There have always been punishments for people who did not pay back their debts and there always have been people being banned or excluded from communities. This is a matter of law, and there is no law without jurisdiction. If we are really getting to operate more like tribes, as the author Seth Godin believes, then that jurisdiction may be tribal law. Alternative currencies potentially warrant a punitive “state within a state.”

Another issue, and this might take another conversation, is the relationship between branding, reputation and the law. Since branding is effectively reputation management, you can consider libel and defamation law part of the branding discourse. In a recent project for Bloomberg Businessweek, we’ve called it “Reputation Governance.” Their question to us was to do a speculative rebranding of AIG, the insurance company.

WD: On your website, you publish a 2007 report by the Council of Europe’s Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights on “secret detentions and illegal transfers of detainees involving Council of Europe member states.” Why?

DvdV: In Europe, the War on Terror was the ideal object of anti-Americanism. But European countries participated in it. In Uncorporate Identity, we’ve said a few things about the totally unremarkable passenger jets used to transport the detainees. We were interested in these planes for reasons of form, too — they were plain white, which we called “administrative stealth.” There was a “mean modernism” — “the compliance of the divine neutrality of the Swiss International Style with the practice of extrajudicial punishment.” Putting the link to that report on our site was a precursor to an attempt at engaging with the “aesthetics” of the War On Terror, knowing how thorny the subject is. Ironically, these white planes and the black metal logos mentioned earlier sit in the same category of “stealth.”

WD: Concerns about immigration and related controversies are paramount in your work. In the spirit of your poster about the mistreatment (and death) of immigrants in the Netherlands, do you have plans to address this issue head on, in a way that might produce direct results? Are you ever tempted to become more activist in general?

DvdV: Making that poster on the mistreatment of immigrants was activism for us; it was a commission, too. Did it produce “direct results”? I doubt it. Action and result are different things. Once people get organized politically, they will at some point be activists. That doesn’t mean they’ll want to establish a meaningful relationship with designers. We designed a large political poster for Euromayday 2008. The organization’s input consisted of their removing a slogan from it. In the end, the activist clients did not even pick up the posters from the printer. That should remind one that the only way not to forget about these posters is to pick them up yourself. You can only be your own activist.

WD: As you’ve noted, Metahaven’s partners are also educators. If you could design a general curriculum for graphic design undergraduates today, what courses would you require? Assuming the normal time constraints of a college education, what courses would you stop teaching? (Assume the one pair of shoes in, one pair out model.)

DvdV: In design school, it is not just about the curriculum but about the way you interact through it with others. People have different personalities, different ambitions and ultimately can do different things. In an undergraduate environment, you want to give students good basics — good education starts with the imaginative teaching of basic things. The following is completely speculative. Were I to redesign an undergraduate course, I would form three islands of basic practice that people could subscribe to, which would start to connect and link as the study progresses. Students cannot just leave the island they’re on and hop to another along the way. For them to change they have to expand their island and make it bigger, so they get nearer to or farther away from other islands. They have to stay faithful to their initial choice even if it was not the best choice. If they start out in “corporate identity” but find they really want to be in “social media,” they have to make their corporate identity be more like social media. At least in the Netherlands, some of the reforms of art schools have resulted in students hopping their way through the curriculum in a completely haphazard way without learning anything. What I argue for is the idea of staying faithful to an initial choice that teaches basics — then expanding as your interests develop. The curriculum could never pre-design the encounters. Students find out that what had seemed to be their choice for a single direction actually does not warrant their autonomy but brings them in contact with others who chose differently. I also don’t like design cliques. People who sit together and all agree that they’ve got it right (and consequently others got it wrong). You have to have difference, and sensitivity to difference as an idea, in order to make an exceptional school. But the same goes for having a studio.

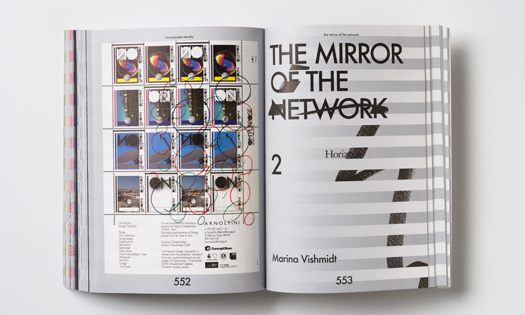

Metahaven, spread from Uncorporate Identity, 2010

WD: A graphic design question. My partner Jessica Helfand has been recently named head of the design sub-committee of the U.S. Citizen’s Stamp Advisory Committee, a public commission of the U.S. Postal Service (and a mouthful, as can be expected from a government bureaucracy). Whatever one thinks of the design of U.S. stamps, it is still a holy grail for a designer, dating back to Bradbury Thompson, Howard Paine, and Andrew Wyeth. The history of design as a part of the Dutch PTT is even richer, with so many of your Dutch peers having contributed stamp designs.

It seems obvious that stamps would interest Metahaven given your interest in national identity. And you have designed stamps (and coins and flags) as part of many projects (Sealand, Myths, Future Echo, Blackmail). But to many, postage stamps also seem like an antiquated graphic form (and certainly a dying media form given the impact of networked communications). What is it about the tiny space of a postage stamp that is so compelling to a graphic designer?

DvdV: There is no big without small. Stamps are currency. And ironically that makes their particular designs irrelevant up to a point, but all the more revealing; it doesn’t matter whether a stamp has the face of Michael Moore or a bald eagle on it — if it was decided so, these will both have the same value. We are interested in stamps demarcating a jurisdiction rather than an identity. The stamp as an object may disappear, but other things will take its place. Funky bar codes for example. Or tags with faces on them that can increase your Facebook social capital if you photograph them using a camera that has face recognition switched on.

WD: I cannot image Metahaven without Google search — the ultimate reflection of a new standard in networked knowledge. Any last thoughts?

DvdV: Google search was the be-all and end-all of our first project, about Sealand. But I guess we have moved beyond that idea, so now you would think of tumblr, fffound or Wikimedia Commons. Work can exist in many places as long as it is out there and not just in your head. Google image search is one of the ways work can appear and disappear for viewers, but as we replace our Sealand-shaped 2005 web site in the near future with something new, that Google image search profile may change. Don’t count on it. The nice thing about making a book like Uncorporate Identity is that you have a place where the work sits together with other work and words, and you can look at it again, not glance at it on a screen (well, obviously, you couldn’t, but other people have told us they can). The “networked knowledge’ embodied in Google search is only as rich as the query. If you Google “Lady Gaga,” what you get is Lady Gaga unless you are more specific. We would like to be able to Google “mid-size images from blogs disagreeing with that The New York Times article about Lady Gaga, which maintain affiliations with the Tea Party.”

Are we demanding too much?