It’s not easy being mean.

This, from a letter to The New York Times a couple of days after Steve Jobs died:

“The ultimate measure of a human being is not the objects he produced but the way he treated other people — especially those over whom he had power or authority. And on that measure, Mr. Jobs fell short.”

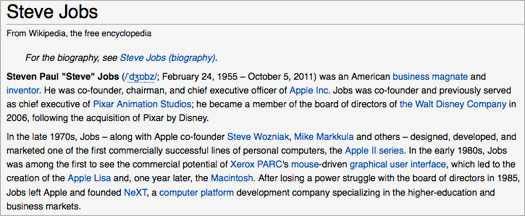

Leaving aside the highly arguable point about how we measure human beings — whose personalities may ultimately matter far less than the things they create — I think that letting Jobs’s notorious tirades at those he thought were doing less than they were capable of overshadow his accomplishments indicates a softening of the disciplines of design and business that may help us all get along, but won’t necessarily produce the next iMac or iPad.

In a recent New Yorker, financial columnist James Surowiecki described perfectionism á la Jobs this way:

“Jobs believed that, for an object to resonate with consumers, every piece of it had to be right, even the ones you couldn’t see.”

Clearly, the gut impact of a product was a concern for Jobs; he had an instinct for designs that satisfy both the head and the heart. His belief that every little thing matters, and that a great product should resonate emotionally as well as technically — harks back to the great woodworkers of an earlier age, who felt that the inside of a drawer should be no less well-made and appealing than the outside. In his bedrock belief that everything matters, Jobs was more like a great architect than a corporate CEO. And getting the devilish details to behave is no easy thing to accomplish.

An editor and columnist for a Forbes technology magazine in the nineties, I heard lots of tales about Jobs and wrote quite a bit about him. From a photographer friend, Doug Menuez, a chronicler of Silicon Valley who did a remarkable photo essay about the development of the Newton, an ill-fated but important precursor to the iPhone, I got accounts of Steve’s volcanic tirades at engineers who somehow fell short of his vision (which almost everyone did sooner or later). There’s no question that he had a habit of publicly belittling anyone who presented a development the first time around. Those castigated would slink back to their cubicles, possibly dreaming of Mafia hits on the boss. But later they would come back with something better than what they’d thought was quite good enough just a few days before. As a result, perhaps, Jobs had good reason to feel that a good ass kicking was an effective way to raise the bar.

Discipline has taken on negative associations, especially in the abundant modern literature of raising children. And since there aren’t many people these days with much tolerance for being pushed around, the tough boss has become indistinguishable from the bad boss. So rather than fight the tide and try to prove that toughness can work better than tenderness in producing great product designs, let me suggest a little memory experiment. Think back to your favorite high school teacher, or rather the teacher you remember with the most respect. Was it that nice guy who wanted to be everyone’s best friend, the one who gave you A’s for what you pretty much knew was B work at best (or maybe not even that good)? Or was it the unsmiling, hard-to-please man or woman who demanded that you knock yourself out to reach a level of comprehension you wouldn’t have thought possible? The teacher I remember most fondly was an implacable taskmaster who taught music and choral singing. She was so tough that even jocks joined the choir and showed up an hour early for school every day of the week. If you made dumb mistakes or slacked off, she was merciless. But she had us singing Bach and Beethoven so well that we were invited to perform all over the East Coast. I doubt that anyone who had her for a teacher has ever forgotten her.

At some low ebb in my life, I was desperate enough to join the Marine Corps, where discipline has a very favorable meaning. The rigorous curriculum of Parris Island was administered for my training platoon by one Gunnery Sergeant Wells, a formidable drill instructor who had come back from Korea with a bronze star but had left behind a couple of fingers. Wells never let up, and though long on demands and punishment he was extremely short on praise or rewards. But those of us who survived his hellish 13-week ministrations left the island with self-confidence that would never have sprung up by chance. If he had gone easy on us, would we have ended up as a few good men? I doubt it. Much later in my life I had the great luck to work at CBS magazines under the editorial eagle eye of Harold Hayes, the legendary editor of Esquire in one of its finest incarnations. Harold could be an ogre if the magazine you happened to be working on was not up to his old Esquire standards. And he was troubled by a bad back in those days, which didn’t make him any less abrasive. But we did some terrific work for him, at least in part because we were afraid not to.

I’ve been a boss on several occasions, and I have to admit that I’ve been, aside from a few temper tantrums, a soft touch. Partly it’s because I believe in treating people well, but largely it’s been because I’m fairly lazy, and it takes a lot more energy to be demanding than to settle for good enough – or just to take on a job oneself instead of pouncing, Jobs-style, on someone who should have done it better. The Sergeant Wellses and Harold Hayses of the world don’t allow shirking the hard labor of perfectionism, in themselves and in others.

As for the Times letter-writer’s contention that how we treat people matters more than what we produce and leave behind, well, that’s just complete crap. We don’t know a lot about William Shakespeare, but do we care whether he was nice to his fellow actors? What we care about is Hamlet and King Lear. General George Patton was a well-documented son of a bitch to serve under, but he defeated Erwin Rommel, one of Germany’s greatest military leaders, and his Third Army in Europe captured more territory in less time than any force in history. So some might wish that Steve Jobs had been the Mr. Rogers of innovation, but as I write these words on my Mac, as I have written everything on a Mac for the past 27 years, I can only be grateful that he was so very hard to please.