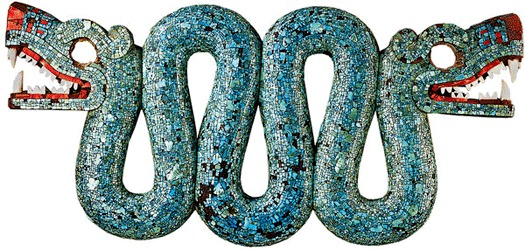

Double-headed serpent Aztec figurine from Mexico (A.D. 1400-1600), part of a project to tell the history of the world in 100 objects from the British Museum.

I’ve been told that our civilization will be known for our diaper landfills and our nuclear waste sites. Other fragments of our culture might survive as well: bits of Tupperware, mountains of lithium batteries or maybe the traces of our highway system. The foundation of a skyscraper might make for a breakthrough excavation but the islands of plastic bottles floating in the oceans may prove puzzling. Perhaps we will bury a cache of digital archives somewhere, to be deciphered one day like the hieroglyphics on an Egyptian sarcophagus.

These thoughts came to mind while I was leafing through A History of the World in 100 Objects by Neil MacGregor, an impressively erudite and readable collection of mini-histories drawn from the expansive collection of the British Museum. After the glut of holiday object giving, this book functions like two tabs of Alka Seltzer; the fizz of its intelligence counteracts the hangover of over-consumption.

Who would have known that 7,000 years go in Japan people were using the first ceramic pots to make soup from oysters and clams? The Jomon pot is beautiful in a muted kind of way: it’s of a coiled construction, latticed on its surface with fibers, and molded into a basket-like shape.

These pots transformed a culture. Food previously had been stored in baskets (prone to decay) or in holes in the ground. Now you could not only cook up a fish stew but you could also store food in a way that “kept freshness in and mice out.” This was a simple yet profound innovation.

Things, and their making, tell us more about a culture than any other mode of cultural expression. Design, in the broadest sense of the word, is a gateway to history. Interrogate a Ming bowl, a Hebrew Astrolabe, a Hawaiian feathered helmet, or a Sudanese slit drum and trade routes, social hierarchies, population movements and the rise of cities can all be deduced.

If this sounds dry, think again. MacGregor’s chapters, often four or five pages long, are bite-sized narratives packed with extraordinary historical detail. The best of them revolve around conflict or mystery. These are non-fiction stories based on things.

Take the case of an Australian bark shield. It’s a beautiful lozenge of reddish brown Mangrove wood about 40 inches high with a hole near its center. On April 29, 1770, on a clear Sunday afternoon, Captain James Cook sailed into what would later be called Botany Bay in Australia. Two men stood on the shore. When Cook and his men approached, they tried to “oppose” the landing party and Cook fired his musket, aiming between them. It had no effect. The two natives gathered up their “darts” and threw a stone. Cook retorted by firing a second time. He hit one man “yet it had no other effect than to make him lay hold of a shield or target to defend himself.” He advanced down the beach but soon ran away, dropping his shield.

This shield was one of the first objects brought back to England by Cook from Australia. We have Cook’s written account of the fateful encounter. But for the man standing on the shore, who represented a people who had lived in that land for some 60,000 years, and who could not write his account of his encounter with the Europeans, we only have the shield. But the shield, says MacGregor, is his statement.

Then there is the case of the jade ax. Another stunning object: a polished green teardrop, smooth to the touch, but with a razor sharp edge. For years the ax was cloaked in mystery. It was clearly all about aesthetics: its reflective surface is polished to a mirror-like shine and it had clearly never been used. But more mysteriously: there is no jade in England or anywhere near England. Jade is normally found in the Far East and in Central America, thousands of miles away. How did it, some 6,000 years ago, get there? The archeologists were baffled.

But in 2003 after twelve years of exploring the Italian Alps, two archeologists discovered blocks of jade high up in the mountains. They deduced that fires had been set near these blocks, large chunks were chipped off, and the blocks were then laboriously carried back down the mountainside. They were hauled for miles and probably broken apart and hewn by craftsmen in Northern Italy.

But because jade is so hard to sculpt these ax heads were then carried hundreds of miles to North West France where they were refined and polished. This particular ax head then made its way to England. With Sherlock Holmes like detail there is one last twist to the tale. Because of the specificity of jade’s geological signature, the archeologists were able to source the exact boulder high in the Alps from which this 8 inch ax head had come.

This book is hefty, weighing in at 707 pages, but I’d still recommend reading it while soaking in the bath, or riding on the subway, or best yet, nestled on a sofa on a Sunday afternoon. What better place to read the story of the rhinoceros that came to Europe from India in 1515 and whose woodblock portrait was made by one Albrecht Dürer?