The symbolism of the number 9 spans from Norse mythology to Pythagoran numerology, Satanic myth to Hindu worship. In India, the nine-day festivals of Navratri are observed as sacred opportunities for the worship of the Divine Mother. Cats, as we all know, are often rumored to posess 9 lives. Cloud 9 is where we’re meant to go when we we’re really happy. (Behavior borne of too much happiness, on the other hand, might send you directly to one of Dante's 9 circles of hell.) The Feynman point is a sequence of six 9s, the US Supreme Court is comprised of 9 justices, the Ramadan is the 9th month of the Islamic calendar, and hey — as long as we’re going the whole nine yards — 9 also happens to be the shoe size of a certain darling Clementine. It’s the name of a rapper, the title of a noodle restaurant in California, and the number Roy Hobbs wore in The Natural. It was former Major League right fielder Reggie Jackson’s number, too. (He wore it for nine years.)

In 1982, the American composer Maury Yeston reimagined Fellini’s 8½ as a musical, which he called Nine. (This November, it will be released as a movie starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Penelope Cruz.) The story concerns Guido Contini, a famous director whose immobilizing writer’s block is told through a series of dreamy flashbacks that mostly serve to dramatize the irony of his isolation: the long-suffering Guido is, as it happens, constantly surrounded by women.

8½ was easily Fellini’s most autobiographical picture, and its musical incarnation deepens Guido’s character study by teasing out the tensions between one man’s vices and virtues, his past glories and his projected fears. On the stage, what becomes startlingly clear is the degree of emotional isolation that characterizes the life of a creative genius. In one song, Guido’s wife, Luisa, describes it thus:

My husband makes movies.

To make them he lives a kind of dream

In which his actions aren't always what they seem.

He may be on to some unique romantic theme.

Some men catch fish, some men tie flies,

Some earn their living baking bread.

My husband, he goes a little crazy,

Making movies, instead.

Fair enough: the idea that protagonists originate in the psyche of their authors is hard to dispute. That they become fictional extensions of their creators isn't all that complicated. That Fellini (and Yeston, for that matter) viewed Guido as a kind of puppet makes total sense.

But what if the character in question really is a puppet?

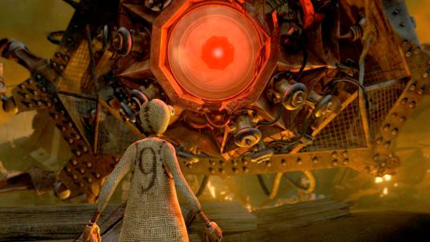

9, (not to be confused by John August's The Nines or Neill Blomkamp's District 9) tells the tale of a group of “sentient ragdolls” who try to combat the forces of evil that have left them sparring for their lives in a barren, post-industrial wasteland. Tim Burton, who co-produced 9 with Timur Bekmambetov, lends his signature Gothic chill to this film, and contributes to its cryptic, if endearing note of human optimism. (You have to really go out on a limb for this, but trust me: it’s there.) The editing is superb, the lighting nothing short of spellbinding; the score, too, is percussive and charged. The characters themselves — miniature burlap-clad figures called “stitchpunks” — recall the rounded edges of many beloved Pixar characters (Sully and Boo in Monsters, Inc., Woody and Buzz in Toy Story); like them, they prance about with a kind of Martha Graham-inspired grace. The same holds true for B.R.A.I.N., the villainous monster, whose giant, knobby head so vividly recalls the ball of the old IBM selectric typewriter — a detail that anyone born before, say, 1975, will find simply irresistible.

But the nod to Pixar doesn’t end there. For starters, there’s an obvious similarity to last year’s Wall-E, staged similarly against a backdrop of post-apocalyptic doom. Both deftly maneuver the immense scale of their imagined landscapes, dwarfing the action as it unfolds. And each film boasts a minuscule protagonist, whose peregrinations are marked by a rather hefty dose of silent wandering. It’s not that both films position these small, seemingly helpless avatars against the big, bad, powerful world of industrial waste. It’s not that they display their technical virtuosity with scale and drama and astonishing lighting, or that they’ve managed to capture the high-tilt danger necessary to the financial survival of any commercial film release. It’s not even that, commendable as it is, they’ve mastered the ability to make mechanized bugs look cute. No: it’s something much more essential than this, something that says more about the filmmakers, perhaps, than the film.

“Every portrait that is painted with feeling,” noted Oscar Wilde, “is a portrait of the artist — not of the sitter.” And these movies are, I think, deeply personal: strange, since they’re marketed as movies for kids, and positioned as dystopic thrillers, albeit kiddie ones. (The New Yorker's Anthony Lane calls it "Apocalypse Lite.") They’re dark, yet hopeful; scary, yet sentimental. Are they deftly couched confessions of fear, of global anxiety, of mid-life apprehension?

Could they be autobiographical?

I confess to finding myself mysteriously drawn to the multiple ironies here. First, of course, that movies made by adults using childlike figures gesture to larger, pretty fundamental themes like good versus evil, technology versus nature, power dueling vulnerability, the future pitted against the past. Second, that they reach back, way back to pre-digital classic forms of entertainment — cabaret chanteuses, movie musicals, wind-up grammaphones and tape recorders — to express beauty in a morally imperiled, post-digital world. (There is a scene in 9 that takes place in a dusty old library, filmed as though it were an amusement park.) Third, that they combine futuristic technology with primal forms, so the machine/animal divide is blurry and spooky and real. And finally, that the more alien the characters, the more human their predicaments.

And that's just the point. In the end, the stories that endure do so because they gesture to something endearingly human, which makes them not only timeless, but also, well, personal — even autobiographical. It’s precisely this flirtation with humanity that lends 9 its soul, just as it did for Wall-E. (Sylvain Chomet's Triplets of Belleville warrants inclusion in this pantheon, too, and in addition to brilliantly balancing that line between made-up and real, surpasses even Pixar in its loopiness.) Like a good graphic novel, these modern animated tales engage because they don't try to be too serious, or too silly, or too sensationalistic even as they are, in fact, all of these things. And if we're drawn in by the paradox — well, isn't that just a human condition?